- Heather Cox Richard on the “cowboy myth” that informs the Trump presidency;

- How Trump et al are giving billionaires a bad name;

- How Trump has done the most corrupt thing any president has ever done — getting rich from anonymous investors — and how barely anyone cares;

- How the administration’s cuts to science research echo the disingenuous schemes of the tobacco industry and the fossil-fuel companies.

Heather Cox Richardson: April 24, 2025

She writes about Trump and his scandalous administration, beginning with his “Vladimir, STOP!” entreaty on social media yesterday morning. But I’m noting this for her summary of the “cowboy myth” that still permeates some sectors of American political and cultural thought. I noted this in my summary of her book (beginning here).

Trump won the presidency by assuring his base that he was a strong leader who could impose his will on the country and the world. Now he is bleating weakly at Putin.

Trump was the logical outcome of the myth of cowboy individualism embraced by the Republicans since President Ronald Reagan rose to the White House by celebrating it. In that myth, a true American is a man who operates on his own, outside the community. He needs nothing from the government, works hard to support himself, protects his wife and children, and asserts his will by dominating others. Government is his enemy, according to the myth, because it takes his money to help undeserving freeloaders and because it regulates how he can run his business. A society dominated by a cowboy individual is a strong one.

Part of the MAGA myth of a past golden age (which never actually existed). How this has played out:

Leaders who pushed this ideology knew it attracted voters. Once they were in power, they could slash government programs and cut taxes and regulations that kept wealth and opportunity accessible to poorer Americans. They argued that a society works best if wealth and power are concentrated among a few elites, who can direct capital more efficiently than government bureaucrats can. Their rhetoric worked: from 1981 to 2021, $50 trillion moved from the bottom 90% of Americans to the top 1%. But those same people talking about individualism to secure votes also knew that the world has never worked this way. In the twenty-first century, U.S. security and the economy depended more than ever on coalitions and government investment.

They “knew that the world has never worked this way.” Especially not in a society that necessarily requires much global interaction. You can’t shut out the outside world.

As the middle class hollowed out, Republicans hammered on the idea that government action was socialism and the government was a swamp of waste and corruption. Donald Trump rode that rhetoric to the White House in 2016 but was still restrained by establishment Republicans who understood that the modern state underpinned America’s strength. President Joe Biden’s rejection of the Republicans’ economic vision and reorientation of the economy around ordinary Americans made Republicans rally against another Democratic president. They turned back to Trump, backed as he was by the MAGA base marinated in the rhetoric that government is bad, even though their counties are more dependent than Democratic counties on government aid.

Now the dog has caught the car.

And here we are. Who is benefiting?

\

Related items:

The Bulwark, Jill Lawrence, 25 Apr 2025: Trump and His Billionaires Are Giving the Rich a Bad Name, subtitled “So much corruption. So much greed. So much chintzy gold in the Oval Office.”

and

The New Republic, Michael Tomasky, 25 Apr 2025: Trump Just Did the Most Corrupt Thing Any President Has Ever Done, subtitled “He’s using the White House to get rich from anonymous investors—and it’s hardly even a news story.”

Imagine that Joe Biden, just as he was assuming office, had started a new company with Hunter Biden and used his main social media account to recruit financial backers, then promised that the most generous among them would earn an invitation to a private dinner with him. Oh, and imagine that these investors were all kept secret from the public, so that we had no idea what kinds of possible conflicts of interest might arise.

Take a minute, close your eyes. Let yourself see Jim Jordan’s face go purple in apoplexy, hear the moral thunder spewing out of Jesse Watters’s mouth, feel the shock (which would be wholly justified) of the New York Times editorial board as it expressed disbelief that the man representing the purported values and standards of the United States of America before the world would begin to think it was remotely OK to do such a thing. The media would be able to speak of nothing else for days. Maybe weeks.

Yet this and more is what Donald Trump just did, and unless you follow the news quite closely, it’s possible you’ve not even heard about it. Or if you have, it was probably in passing, one of those second-tier, “this is kind of interesting” headlines. But it’s a lot more than that. As Democratic Senator Chris Murphy noted Wednesday: “This isn’t Trump just being Trump. The Trump coin scam is the most brazenly corrupt thing a President has ever done. Not close.”

Remember the outrage over Hillary’s e-mails? That pales in comparison to this. And yet Trump’s fans don’t care. Here again is the break between America’s national ideals, and the base hero-worship of cultish tribalists.

\\\

More about conservatives vs. reality.

NY Times, Alan Burdick, 25 Apr 2025: Trump vs. Science, subtitled “We explain the administration’s cuts to research.”

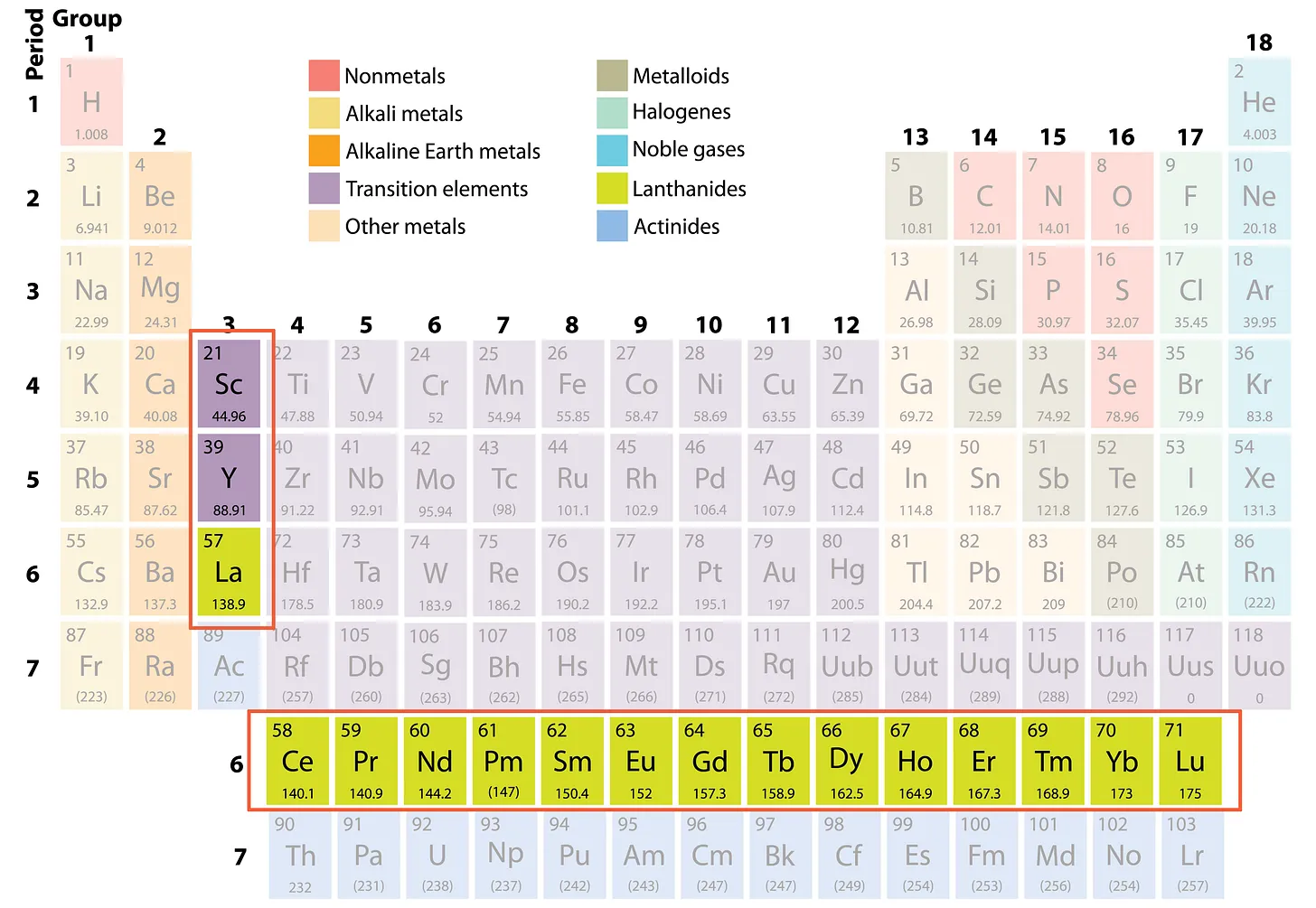

Late yesterday, Sethuraman Panchanathan, whom President Trump hired to run the National Science Foundation five years ago, quit. He didn’t say why, but it was clear enough: Last weekend, Trump cut more than 400 active research awards from the N.S.F., and he is pressing Congress to halve the agency’s $9 billion budget.

The Trump administration has targeted the American scientific enterprise, an engine of research and innovation that has thrummed for decades. It has slashed or frozen budgets at the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and NASA. It has fired or defunded thousands of researchers.

The chaos is confusing: Isn’t science a force for good? Hasn’t it contained disease? Won’t it help us in the competition with China? Doesn’t it attract the kind of immigrants the president says he wants? In this edition of the newsletter, we break out our macroscope to make sense of the turmoil.

How science is an investment in the future; how American scientists are being alienated and moving to other countries. And then this: redefining science.

These are mechanical threats to science — who gets money, what they work on. But there is a more existential worry. The Trump administration is trying to change what counts as science.

One effort aims at what science should show — and at achieving results agreeable to the administration. The health secretary, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., wants to reopen research into a long-debunked link between vaccines and autism. He doesn’t want to study vaccine hesitancy. The National Science Foundation says it will no longer fund “research with the goal of combating ‘misinformation,’ ‘disinformation,’ and ‘malinformation’ that could be used to infringe on the constitutionally protected speech rights of American citizens.” A Justice Department official has accused prominent medical journals of political bias for not airing “competing viewpoints.”

Another gambit is to suppress or avoid politically off-message results, even if the message isn’t yet clear. The government has expunged public data sets on air quality, earthquake intensity and seabed geology. Why cut the budget by erasing records? Perhaps the data would point toward efforts (pollution reduction? seabed mining limits?) that officials might one day need to undertake. We pursue knowledge in order to act: to prevent things, to improve things. But action is expensive, at a moment when the Trump administration wants the government to do as little as possible. Perhaps it’s best to not even know.

And how calls for “further research” are disingenuous: “It’s an old playbook, exploited in the 1960s by the tobacco industry and more recently by fossil-fuel companies.” As we’ve read about in a couple books lately. (Newitz, O’Connor and Weatherall)