Saw the movie INHERIT THE WIND today for the first time in many years. This is the 1960 film version of the 1955 play by Jerome Lawrence and Robert E. Lee, as directed by Stanley Kramer, about the famous 1925 ‘monkey trial’ in a small town, Dayton, Tennessee, in which a high school teacher was accused of teaching Darwin’s theory of evolution in spite of a state law prohibiting such instruction.

(I’d put the film on my Netflix quere literally years ago, and somehow last week, without my having noticed my queue in a while, the DVD appeared in my mailbox…)

The subsequent trial attracted national media attention and two big-name lawyers. (That the teacher violated the letter of the law was barely the issue; of course he did. The big-name attention was about whether the law was justified.) The play and movie fictionalizes the characters, but their identities are easily mapped to their real-life counterparts. The prosecuting attorney in the play/movie is Matthew Harrison Brady, counterpart of the actual William Jennings Bryan, the three-time (losing, obviously) presidential candidate, who speaks for the literal word of the Bible; the defense attorney in the play/movie is Henry Drummond, counterpart of the actual Clarence Darrow, a firebrand attorney known for defending unpopular clients. And attending the proceedings is a sarcastic newspaper reporter, E.K. Hornbeck, counterpart of the real life H.L. Mencken. (In the film, Brady is played by Fredric March, Drummond by Spencer Tracy [an Oscar nominee for this], and Hornbeck by none other than Gene Kelly. And Dick York, later known for his husbandly role on the TV series Bewitched, played the school-teacher, Bertram Cates. Also notable is Claude Akins as the overly-zealous Reverend Jeremiah Brown — father of the young woman in love with Bertram Cates.)

The story pits small-town Bible-thumpers — “simple folk”, “plain folk”, they are repeatedly described as, who need the comfort of their Bible stories, against outsiders from the ‘northern cities’ and foreigners — resisting ideas of ‘evil’-ution, which to them means humans descended from apes and ultimately slime [a gross misunderstanding and mischaracterization, needless to say]. The town crowd repeatedly marches through the streets, singing “Give Me That Ol’ Time Religion”, and carrying signs (e.g. “Brady and Bible, Drummond and Devil”), that are too well-spelled (considering the actual recent record of reactionary protest marches) to be realistic. The town crowd is much like the hysterical mobs of “The Crucible” — at one point they parade through the streets singing about hanging and burning the teacher, Bertram Cates, as he waits in his jail cell.

Which is to say, the movie overplays it, exaggerating the ignorant zealousness of the townspeople, and for that matter the zealousness of Matthew Harrison Brady, who in his passion and small-mindedness comes across as a buffoon, and dies himself to a heart-attack in the midst of a passionate oration just after the trial ends.

I say this even after, obviously, not being on the town’s or Brady’s side in this debate. But maybe this exaggeration was dramatically necessary when this film was made, at a time when these issues were not so visible as they are today.

Of course, as with pretty much all plays and movies based on real events, this story takes liberties with historical facts. (Bryan died five days after the trial ended, not on the last day of the trial, for example.)

Dramatically, however, the story is incendiary. It’s mostly about the trial, and it takes off when, after Brady and the judge have ruled out testimony from various university experts in zoology, geology, and whatnot, Drummond calls *Brady* to the stand, to interrogate him about the Bible and “Mrs. Cain” and about whether the first day was literally a 24-hour day, a dialogue that leads to Brady’s claim that God speaks to him. It’s a long, impassioned scene that culminates in Brady’s breakdown, the crowd’s subtle turn against him, and how the ultimate verdict against Cates seems like a joke. (After so many days or weeks of media attention, the town’s leaders realized that the country, and even the world, was treating Dayton as a laughing-stock. And so the judge minimized the sentence as best he could.) [Not mentioned in the play or film: the verdict was later overturned on a technicality.]

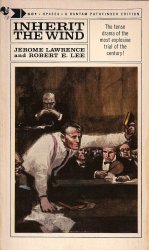

I read this play in my teens, long before I saw the movie. It was published in a paperback Bantam Pathfinder edition, for 60 cents, that I bought off a junior-high school book cart, and which I’ve scanned here (without color correcting). In those days the junior high school “home room” class hosted a book cart, like a large library cart, that was wheeled into home room once a week, from which one could purchase books. I was especially attracted to Bantam Pathfinder editions, and bought this one (along with William Gibson’s play The Miracle Worker, Leonard Wibberley’s The Mouse That Roared, C. S. Forester’s Sink the Bismark!, and others, including my first few Ray Bradbury books).

As I watched the movie today, I couldn’t help but pick up the book, and track the film to the play. And I was surprised to discover that the film is actually *longer* and more developed than the play; there is some rearrangement of scenes from the play, but there are also entire scenes in the film that were not in the play, especially a couple involving the preacher and his daughter, and some rearrangement of the final scenes with Hornbeck and Drummond. At the same time, considerable portions of the film are taken word for word from the play. So I’m surprised to see that, according to Wikipedia, the film’s scriptwriters were not the playwrights; most scriptwriters take much more liberty with their source material than these two obviously did.

Reading the play at age 15 was just one ingredient among many that formed my worldview in those impressionable years. Later, I saw a performance of the play at UCLA, while I was a student there, and eventually the movie.

Here’s a key passage — among many — from the play.

Brady:

We must not abandon faith! Faith is the most important thing!Drummond:

Then why did God plague us with the power to think? Mr. Brady, why do you deny the one faculty which lifts man above all the creatures on the earth: the power of his brain to reason. What other merit have we?

Fun facts and asides:

- I understand there is a museum in Dayton, Tennessee, about the Scopes Trial, that emphasizes the historical inaccuracies between the play/movie and what actually happened. As if.

- According to Wikipedia, the Cowardly Lion in L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz was a satirization of Bryan.

- Bryan was a Democrat, who “champion[ed] the ideas of the farmers and workers” [Wikipedia] while also being a religious zealot who “actively lobbied for state laws banning public schools from teaching evolution” [ditto]. How times have changed.

- Surprised to note that according to Wikipedia there have been three subsequent TV films of the play, in 1965, 1988, and 1999

- And interesting to note that Wikipedia characterizes the play as a parable about the McCarthy ‘witch-hunt’ trials concerning communists, since of course the content of the story’s subject can be taken at face value — there are in fact battles ongoing in school boards to this day (especially in Texas and other southern states) about whether science should be prohibited in school classrooms in favor of religious myths.

- Here’s a very weird coincidence, which I will note but not explain in this venue; according to my book of the play, which lists the cast of the 1955 NYC production, the first character on stage, in the character of Melinda, was played by Mary Kevin Kelly.

- FWIW, in that original production, Tony Randall played E.K. Hornbeck, Ed Begley played Matthew Harrison Brady, and Paul Muni played Henry Drummond.

—

Edited 24nov14: added a couple sentences above about how the teacher did actually violate the letter of the law, and how the town was made a laughing-stock through all the media attention.