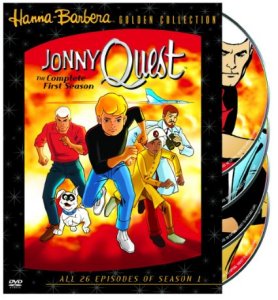

Speaking of rewatches of favorite childhood shows, I have in fact finished a ‘rewatch’ of one of my earliest favorite TV shows, the 1964 animated series ‘Jonny Quest’, via a DVD set I bought some years ago and haven’t watched until now, over the past three weeks. The show was broadcast from 1964 to 1965, lasting only one season of 26 episodes, in the same era as Bewitched, Gilligan’s Island, The Addams Family, Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, and Flipper. In retrospect, this may have been the earliest show I saw that had science-fictional elements, a year before Lost in Space (which I only discovered about half-way through its first season) and two years before Star Trek. Somewhat like those shows, JQ has developed a long-lasting fan base, and relative immortality via DVD (and a few episodes on YouTube).

Speaking of rewatches of favorite childhood shows, I have in fact finished a ‘rewatch’ of one of my earliest favorite TV shows, the 1964 animated series ‘Jonny Quest’, via a DVD set I bought some years ago and haven’t watched until now, over the past three weeks. The show was broadcast from 1964 to 1965, lasting only one season of 26 episodes, in the same era as Bewitched, Gilligan’s Island, The Addams Family, Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, and Flipper. In retrospect, this may have been the earliest show I saw that had science-fictional elements, a year before Lost in Space (which I only discovered about half-way through its first season) and two years before Star Trek. Somewhat like those shows, JQ has developed a long-lasting fan base, and relative immortality via DVD (and a few episodes on YouTube).

Yes, this was an animated series, thus relatively a kids’ show, but it was far more sophisticated than other animated series up until then, deliberately produced to be more realistic, in terms of characters and settings and premises, than the other animated shows of the time (Flintstones and The Jetsons).

The series was based on earlier comics books and radio series, such as Terry and the Pirates. After watching the DVD series, this past week, I discovered this remarkably sophisticated documentary about the show on YouTube, 2 hours long though broken into three parts. It provides a lot of background and context about the show that I didn’t appreciate until discovering it this week. The show’s heritage was earlier comics and radio series by Alex Toth and Doug Wildey; the studio heads William Hanna and Joseph Barbera – Hanna/Barbera – hired Wildey to create a show based on the long-running radio series Jack Armstrong: The All American Boy — and was sketched into animation in scenes still shown in the end credits of Jonny Quest (that are not from any JQ episode). The producers changed their minds, and asked Wildey to create a new show with new characters. His creation was called “The Sage of Chip Balloo” – before the producers changed the kid’s name to Jonny Quest.

So: the show is about Jonny Quest, his father Dr. Benton Quest, a world-renowned scientist, Quest’s pilot and bodyguard “Race” Bannon, and their ‘adopted son’ Hadji, an Indian boy who saved Dr. Quest’s life while visiting Calcutta. The episodes involve various investigations by Dr. Quest, who seems to have a new scientific specialty each week (sonic waves one week, lasers another, sea fish another, a rare mineral to support the space program on another) or who is challenged by alerts from old friends (a colleague who is captured by jungle natives) or threats from comic-book character Dr. Zin (via a robot spy, etc.)

The show had an international quality. The Quest team was based at Palm Key, an imaginary island off Florida, but each week’s episode took them to any number of places around the world, via their various high-tech jets. That was another key theme: the inclusion of various high-tech, for the 1960s, gadgets. Lasers, VTOL jets, personal video communicators.

There were a few science fiction and fantasy elements — anti-gravity, a robot spy, a true yeti, a true mummy, not to mention Hadji’s various magic tricks (“sim, sim, sala bim!”) — but just as often the plots involved various nefarious bad guys, evil geniuses or nonspecific representatives of various foreign governments, with no fantastic elements.

A key point about all these old TV shows (including LIS and Trek!) is this: the makers of those shows assumed they were making disposable goods, to be seen once and forgotten, like (in the words of one of the people in this JQ documentary) using a Kleenex and throwing it away. The TV era of the 1960s was long before video-casette recorders (VCRs) and DVD players, let alone YouTube; I suspect young people today don’t appreciate how transient was the TV work of half a century ago. The creators of TV shows of that era would have been amazed to think that their work would survive 50 years and be subject of analyses and documentaries. Which, among other things, is why we later viewers need to give them some slack about errors and inconsistencies. They did a pretty good job, all things considered.

Another personal point: Like LIS and Trek, and any number of other shows that affected me in my 1960s childhood: I didn’t necessarily see all the episodes of any of these shows when first broadcast. I saw most of them in syndicated reruns in later years, in the 1970s and beyond. But when syndicated, episodes were trimmed by local broadcasters, to allow for more commercial time. Which means that, even of my favorite shows (Trek), I’m not sure I’ve actually ever seen every scene of every episode. I’m fairly sure this is true for *every* show I watched from that era… which gives me some incentive to do some deliberate re-watches of those shows, via DVDs, now that I have the time to do so.

Back to JQ: The documentary also reveals that the DVD that I just watched has incorrect credits for most episodes – which credits indicate that one William D. Hamilton wrote all the episodes but the very first one, which would have been an amazing feat! But in fact there were many writers, including Walter Black, Joanna Lee, Charles Hoffman, and others. (Though Hamilton did in fact write quite a few.)

The documentary includes some interviews, with the likes of Brad Bird, expressing their appreciation for the show. Among many incidental facts discussed is the music of Hoyt Curtin, the voice work of Vic Perrin (the “control voice” of The Outer Limits, and a guest in episode of Trek, and the voice of numerous JQ villains), and the idea of “planned animation” that made weekly animated series possible.

The documentary identifies fan favorite episodes, but I will conclude with my own take on the coolest episodes: “The Robot Spy”; “Turu the Terrible”; “The Invisible Monster” (“paint it!”); “Shadow of the Condor”; and “The House of Seven Gargoyles”.