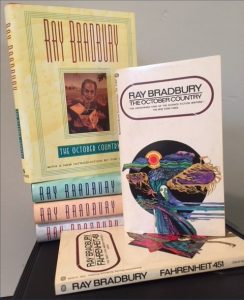

Ray Bradbury’s THE OCTOBER COUNTRY (TOC) was published in 1955, part way through the publication of what I think are Bradbury’s three essential, classic books: THE MARTIAN CHRONICLES (abbreviated in future as TMC; first published 1950), FAHRENHEIT 451 (F451; 1953), and DANDELION WINE (DW; 1957). Many of the stories in TOC were published in Bradbury’s first book, DARK CARNIVAL, published in 1947 by Arkham House and never reprinted; after the successes of TMC and F451, THE OCTOBER COUNTRY revived many of the stories in the earlier book, revising them, while dropping some and adding others.

Ray Bradbury’s THE OCTOBER COUNTRY (TOC) was published in 1955, part way through the publication of what I think are Bradbury’s three essential, classic books: THE MARTIAN CHRONICLES (abbreviated in future as TMC; first published 1950), FAHRENHEIT 451 (F451; 1953), and DANDELION WINE (DW; 1957). Many of the stories in TOC were published in Bradbury’s first book, DARK CARNIVAL, published in 1947 by Arkham House and never reprinted; after the successes of TMC and F451, THE OCTOBER COUNTRY revived many of the stories in the earlier book, revising them, while dropping some and adding others.

THE OCTOBER COUNTRY, in the absence of reprint editions of DARK CARNIVAL, remains the essential earliest Bradbury collection. It’s greatly enhanced by graphic illustrations for each story by Joseph Mugnaini, many of which can be found on the interwebs…see here.

The stories in this book include many of Bradbury’s earliest magazine publications. As I finish up this post, more than half-way through February, having begun to re/read Bradbury since the 2nd of January, I’ve read all of Bradbury collections (and story-cycle semi-novels) through THE TOYNBEE CONVECTOR (1988), more or less in chronological order. It’s worthwhile to have done this before writing these posts, because as you read your way through Bradbury’s career, you see how his focus and themes changed. In his earliest years, getting stories into print in the early 1940s, he was emulating the macabre, ‘weird’ tales that were published in the magazine Weird Tales — stories like “The Wind”, “The Crowd”, and “The Scythe” (all 1943) and “The Jar” (1944), while occasionally attempting the more action-focused, violent stories in a pulp magazine called Planet Stories, these including the very pulpish “Frost and Fire” (published there originally as “The Creatures That Time Forgot”), though not included in a Bradbury book until much later.

Yet as Bradbury’s career blossomed and flourished in the late ’40s and the 1950s, he abandoned simply emulating what other writers were doing, and increasingly based stories on his own experiences and background, through the 1950s and 1960s. Thus: the Green Town stories, based on his childhood in a rural Illinois town; the Mars stories, perhaps based on his family’s stays in Tucson while his father looked for work there, and perhaps by his stay in the LA suburb of Venice, with its actual canals, and by his reading of pulp SF stories in his youth; the urban, suburban, and Hollywood stories, based on his life when he settled in Los Angeles. There were other recurring settings: stories in Dublin (he spent 6 months in Ireland writing a screenplay for John Huston); stories in Mexico (where presumably he vacationed, while living in LA)…..

I have deliberately not investigated various nonfiction surveys of Bradbury’s work, preferring to record my own impressions first. But I do have Sam Weller’s THE BRADBURY CHRONICLES, Jerry Weist’s BRADBURY: AN ILLUSTRATED LIFE, and David Seed’s RAY BRADBURY (one of the University of Illinois’ series of author-themed studies), that I will peruse closely once I’ve finished my own reads of RB books, which will be shortly. (Since the focus of my grand re-reading project is on science fiction, I am disregarding for now SOMETHING WICKED THIS WAY COMES, THE HALLOWEEN TREE, and the later detective novels.)

*

So to commence with THE OCTOBER COUNTRY. For these and many following posts about RB’s books, I’m greatly indebted to William Contento’s “Locus Index to Science Fiction” (http://www.locusmag.com/index/), which, alas, has not been updated online in a decade. I have a 2012 CD-ROM edition of the complete index, which is invaluable for compiling listings of book editions, and their contents, cross-indexed by book title and story title. (The Internet Science Fiction Database, http://www.isfdb.org/, has much the same data, as well as a multitude of references to translations, but I prefer the tighter layouts of Bill’s db, and the source credits in TOCs like the one below.) Thus, for this book THE OCTOBER COUNTRY, Bill’s index shows this table of contents, with citations for original publications of each story:

The October Country Ray Bradbury (Ballantine, 1955, $3.50, 306pp, hc)

The Dwarf · ss Fantastic Jan/Feb 1954

The Next in Line · nv Dark Carnival, Arkham House: Sauk City, WI 1947

The Watchful Poker Chip of H. Matisse · ss Beyond Fantasy Fiction Mar 1954

Skeleton · ss Weird Tales Sep 1945

The Jar · ss Weird Tales Nov 1944

The Lake · ss Weird Tales May 1944

The Emissary · ss Dark Carnival, Arkham House: Sauk City, WI 1947

Touched with Fire · ss Maclean’s Jun 1 1954, as “Shopping for Death”

The Small Assassin · ss Dime Mystery Magazine Nov 1946

The Crowd · ss Weird Tales May 1943

Jack-in-the-Box · ss Dark Carnival, Arkham House: Sauk City, WI 1947

The Scythe · ss Weird Tales Jul 1943

Uncle Einar · ss Dark Carnival, Arkham House: Sauk City, WI 1947

The Wind · ss Weird Tales Mar 1943

The Man Upstairs · ss Harper’s Mar 1947

There Was an Old Woman · ss Weird Tales Jul 1944

The Cistern · ss Mademoiselle May 1947

Homecoming · ss Mademoiselle Oct 1946

The Wonderful Death of Dudley Stone · ss Charm Jul 1954

The value of these listings is that they reveal when the stories were originally published, and especially in RB’s later books, these TOCs show how the contents of those books mixed recently published stories with older stories, a trend and mix that would become more and more extreme as Bradbury’s career progressed. ISFDB (and Contento) both generate chronological lists of publications; ISFDB’s is here, through you have to scroll down a way to get to the short fiction.

I reread this book first, in my Bradbury reread plan in January 2018, and state first of all that while I read this book at age 15 or so, in about 1970, I had never reread it since, until now. So part of my interest in rereading it now was, how many of these stories would I remember, if any..?

The answer is: I remember quite a few, though not all, and ironically that the two stories that struck me especially on this rereading were stories I had *not* remembered.

The memorable stories included those one- or two-word-titled stories “The Crowd”, “The Wind”, “The Lake”, “The Dwarf”, and especially “The Scythe” (1943), a story about a destitute man and his family who realize the crop of wheat he is obliged to keep trimmed is keyed to the actual deaths of people around the world, including, eventually, the man’s own family, with a final gloss that alludes to the wars and atomic bombs of the mid-20th century. “The Crowd” (1943) is about the victim of an auto accident (such as were apparently very common, and deadly, in the 1940s) who realizes that in every accident, the same crowd of recognizable people gathers, with a coda about himself as a victim and becoming one of the watchers. “The Wind” (also 1943) is about an explorer of a Himalayan Valley of Wind who feels pursued all his life by howling winds, and succumbs to them. These stories are essentialist fantasy: the idea that human perceptions and protocols, fears and terrors, represent basic properties of the materialist universe.

*

The two stories that especially struck me were two I didn’t remember.

“The Jar” is a about a small town Louisiana man who visits a carnival and buys a weird thing in a jar, something like a jellyfish, and buys it to take home, with ulterior motives: “And I been reckoning how looked-up-to I’d be back down at Wilder’s Hollow if I brung home something like this to set on my shelf over the table. The folks would sure look up to me then, I bet.”

Indeed, the folks at home are impressed. But each of them sees something different in the contents of the jar. One remembers having to drown a kitten. Another sees the source of all life. Another recalls the swamp. One women recalls her child, lost in the swamp — could this thing be him??

The man’s itinerant wife reveals what it really is: junk, paper-mache, rubber. He doesn’t care, nor do his friends. Published in 1944, this story illustrates what we understand in 2018 as a mental bias: people see in things what they want to see: a baby; a brain; what they want to see, depending on their fears and desires.

*

And then there’s “Jack-in-the-Box,” a story first published back in that first collection DARK CARNIVAL in 1947. This is a fascinating closed-world tale, about a boy who lives in a house with his mother, and a Teacher on an upper floor, but with no experience of the outside world. Edwin has been told stories about Father, who built the house, aka ‘World’, and who was killed by beasts beyond the trees; Mother often calls him God. There is nothing beyond the trees but death, she tells him.

On his birthdays Edwin gets to explore previously forbidden doors in this vast house, and on one of these he ascends to an upper room and window and sees the outside world, beyond the trees that surround his house.

And then his mother dies, and his upstairs Teacher disappears, and he sort of figures things out. And then he runs outside, through the iron gate the surrounds his property, and discovers the real world, of streets and buildings and lampposts. The final scene is from the POV of a policeman, who sees this boy running around, laughing and crying, touching everything, and yelling, gloriously, “I’m dead! I’m dead!”.

My only quibble with this story is the recurrent metaphor of the “jack-in-the-box”, where Edwin has one that doesn’t work and throws it out the window. The story didn’t need it.

*

The most famous story here, I suppose, is “The Small Assassin,” about a woman who fears she is being murdered by her just-born child. The husband consults her doctor; she’s taken home; and one night he trips down the stairs, over a doll. And then Alice trips over the same doll — and dies. The father speculates with the doctor about whether some babies, perhaps one in a million, are born fully formed and intelligent, resentful of being thrust into the world? The father is the next victim, and the story ends with the doctor visiting the house, concluding this must be true, walking up to the baby’s nursery, and wielding… a scalpel.

I can’t help but think of the Twilight Zone episode “Living Doll,” that well-known episode with Telly Sevalas, in which a doll, not a baby, maneuvers the death of the insubordinate father. TZ’s Rod Serling had a reputation for adapting stories from previous sources, sometimes without credit, and I wonder, without any evidence, if that episode might have been inspired by this RB story.

*

Other notable stories:

“The Man Upstairs” (1947) is in retrospect a Green Town story that didn’t make into DW. As in the DW stories, the story is about 11-year-old Douglas, living a large with grandparents and boarders, and how one mysterious boarder, whom we realize is a vampire, is dispatched by Douglas using the same methods his grandmother uses to cut up and eviscerate chickens.

— A key observation from reading some 20 RB books in a row is this: that while RB published THE MARTIAN CHRONICLES and DANDELION WINE, in 1950 and 1957, about Mars and Green Town respectively, neither book contained all the relevant stories he’d written up to those dates, and RB continued to write both Mars and Green Town stories throughout his life. More about this in later posts.

“The Next in Line” (1947, an original in DARK CARNIVAL) is one of the earliest of RB’s Mexico stories, about an American couple visiting a Mexican town where the local graveyard is rented, and when families don’t pay the rent, the bodies are dug up and put into an underground chamber, upright leaning against the walls, as mummies. The story arc is about the tremulous wife, afraid of that chamber, worried about dying, and the story ends with the husband driving out of town, alone. The notion of Mexican towns and graveyards appears in a couple later RB stories.

“Skeleton” (1945) is another famous RB tale, about a hypochondriac man obsessed by the notion that that inside of him is… a skeleton! He’s freaked out by the notion. Some of it is visible — teeth! He repeatedly visits his doctor, then seeks out a ‘bone specialist,’ who comes to his apartment for a private treatment with gruesome results. (Also, there’s another casually mentioned car crash here, as he drives to Phoenix; in this case the protag survives.)

“The Dwarf” (1954) — the first story in the book, and non-fantastic, though a bit macabre, in that it concerns a ‘dwarf’ who attends a carnival every night specifically to look at himself in the distorting mirrors. And it’s about the carnival owner’s sadistic trick, and the reaction to that of his girlfriend. The unchallenged presumption is that dwarfs are horrible little people. Published in 1954.

“The Watchful Poker Chip of H. Matisse” is another 1954 story, about an American living in Paris whom the locals find fascinating just because he’s so… dull and ordinary. When he attempts to become more sophisticated, they lose interest in him. There are lots of now dated cultural references; one that’s still cute is “Does Existentialism Still Exist, or Is Kraft-Ebbing?”.

“Touched with Fire” (1954) recalls Shirley Jackson. It’s about two old men who follow people whom they perceive have a death wish, and try to intervene in their lives. A recurring note here is that the day is hot, nearing 92F, the time when murders happen, and the story ends with the implication their efforts, in this case, have been in vain.

“The Wonderful Death of Dudley Stone” (1954) is about the great writer who retired at age 30 never to write again, and the effort years later by one of his fans (a Mr. Douglas, a recurring name in RB stories) to find out why. The revelation involves a rival writer to Stone, and Stone’s willingness to give up writing forever lest he be murdered — though he had an ulterior motive as well. This is the first of a number of stories that invite comparison to Bradbury’s own life, as a writer or as a family man, which I suspect don’t reveal so much truth as they do the willingness of RB to entertain suppressed demons.

This book also has two of the earliest ‘Family’ stories, those about the weird collection of vampires and others who live in a huge House north of Chicago — “Uncle Einar” (1947) and “Homecoming” (1946), the first story about a gigantic man with wings, the latter about a family gathering that focuses on the one family member with no special talents, Timothy. RB later wove half a dozen of these stories into a semi-novel, in the same sense as DW, called FROM THE DUST RETURNED, published way out in 2001, and which I’ll consider in a future post. I suspect these earliest stories were RB’s attempts to mimic Weird Tales fiction, but since RB sort of merged them with a Green Town setting, and developed the theme of FRDR into his own one grand theme — which I’ll spell out later — he kept writing the occasional one, and eventually completed that book.