DANDELION WINE (DW) is certainly Bradbury’s most personal book, because it is so clearly based on Bradbury’s own life as a boy in small-town Illinois. It was published in 1957 as a novel, not a short story collection, though actually it’s a hybrid, what SF critics call a ‘fix-up’ (http://www.sf-encyclopedia.com/entry/fixup), a book made up of previously published material, strung or stitched together often with added material. Since the book editions of DW do not identify the previous material, once again I’ll copy the TOC from Bill Contento’s Locus Index. (The * after some titles indicates no prior publication; a remarkable number of sections were previously published as short magazine pieces.)

DANDELION WINE (DW) is certainly Bradbury’s most personal book, because it is so clearly based on Bradbury’s own life as a boy in small-town Illinois. It was published in 1957 as a novel, not a short story collection, though actually it’s a hybrid, what SF critics call a ‘fix-up’ (http://www.sf-encyclopedia.com/entry/fixup), a book made up of previously published material, strung or stitched together often with added material. Since the book editions of DW do not identify the previous material, once again I’ll copy the TOC from Bill Contento’s Locus Index. (The * after some titles indicates no prior publication; a remarkable number of sections were previously published as short magazine pieces.)

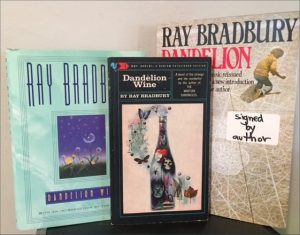

Dandelion Wine Ray Bradbury (Doubleday, 1957, 281pp, hc)

Illumination · Ray Bradbury · ss The Reporter May 16 1957

Dandelion Wine · Ray Bradbury · ss Gourmet Jun 1953

Summer in the Air · Ray Bradbury · ss The Saturday Evening Post Feb 18 1956

The Season of Sitting · Ray Bradbury · vi Charm Aug 1951

The Night · Ray Bradbury · ss Weird Tales Jul 1946

The Lawns of Summer · Ray Bradbury · ss Nation’s Business Feb 1952

The Happiness Machine · Ray Bradbury · ss The Saturday Evening Post Sep 14 1957

Exorcism · Ray Bradbury · vi *

Season of Disbelief · Ray Bradbury · ss Collier’s Nov 25 1950

The Last, the Very Last · Ray Bradbury · ss The Reporter Jun 2 1955

The Green Machine · Ray Bradbury · ss Argosy (UK) Mar 1951

The Trolley · Ray Bradbury · ss Good Housekeeping Jul 1955

Statues · Ray Bradbury · ss *

Magic! · Ray Bradbury · ss *

The Window · Ray Bradbury · ss Collier’s Aug 5 1950

The Swan · Ray Bradbury · ss Cosmopolitan Sep 1954

The Whole Town’s Sleeping · Ray Bradbury · ss McCall’s Sep 1950

Good-By, Grandma · Ray Bradbury · ss The Saturday Evening Post May 25 1957

The Tarot Witch · Ray Bradbury · ss *

Green Wine for Dreaming · Ray Bradbury · ss *

Dinner at Dawn · Ray Bradbury · ss Everywoman’s Magazine Feb 1954, as “The Magical Kitchen” (?)

Bradbury had done something similar with THE MARTIAN CHRONICLES (1950; TMC), but that wasn’t presented as a novel, but as what I call a ‘linked-collection’ of related stories, listed in a table of contents at the front of the book. (Somewhat like Asimov’s I, ROBOT — the same year!) DW has no such TOC; there are page breaks between sections, but no titles. The TOC above shows that the material for this 1957 book was first published in the early 1950s — once RB’s reputation had been established by TMC. My guess is he was relaxing, or indulging, writing what he wanted to write rather than imitating what was popular, and managing to get into the ‘slick’ high-paying magazines, like Good Housekeeping and Saturday Evening Post. Only one of the items above was published in a genre magazine — that fifth item, in Weird Tales in 1946.

There’s a more significant issue with both this book and TMC, one I’d not recalled before embarking on this reread program: Bradbury wrote many more Green Town stories than those in DW; he wrote many more Mars stories than appeared in TMC. He wrote Green Town stories and Mars stories throughout his life. They were his go-to settings for the kinds of stories he liked to write, and there were only half a dozen different kinds of stories he liked to write — or perhaps, there were only half a dozen different settings that he used, over and over, for most of the stories he wrote.

Yet the stories written in any one setting were not consistent. Especially when TMC was assembled, RB and his editor Walter Bradbury at Doubleday (no relation) apparently chose from among RB’s published Mars stories those which were more-or-less consistent, and those which could be fitted into a framework of an overarching story. (Much as what we now call the Biblical “New Testament” was assembled in the 4th century by church officials who chose some ancient texts, those which were more or less consistent, and left out those which were not – and limited the ‘gospels’ to four, on numerological grounds!) So not only were some early Mars stories left out of TMC, but RB continued to use Mars as a setting for later stories, stories that were not necessarily consistent with the broad story arc established by TMC. The same is true for stories set in Green Town, and DW.

In the case of the Green Town stories, for example, those not incorporated into DW, he varied the protagonist’s name, his age, and his family situation. Some Green Town stories have an adult returning to his home town. Some don’t involve the boy Douglas at all, in any guise.

The key issue of DW is that it is almost entirely a realistic novel, with no science fiction and almost no fantasy, save one or two episodes. It’s Bradbury’s homage to his own Arcadia, his Eden, the perfect past that adulthood and progress threatened — that key theme of his entire career.

*

So: DANDELION WINE is about Douglas Spaulding, age 12, as he spends Summer of 1928 in this small Illinois town of Green Town, living with his family in a boarding house and next door to his grandparents’ house. The book opens and closes beautifully with Douglas looking out over the town from the fourth-floor cupola in his grandparents’ house, first at dawn, later at dusk, watching lights go on or off, and imagining himself as a conductor, cueing a performance.

The summer is bookended by two key moments in Douglas’ life: early on, while walking in the woods with his father and younger brother, Douglas has a sense of deep perception and realizes that he’s alive!, in a way he’d never realized before. Subsequently he keeps a notebook of “rituals” and “revelations” that he experiences throughout the summer. Then, near the end of the book, the counterpart realization occurs, as he’s witnessed people in town die, and even as he sees cowboys ‘killed’ in the movies and realizes what death actually means. His great-grandma does die, after saying, “I’m not really dying today. No person ever died that had a family. I’ll be around a long time.” (A sentiment echoed by the recent Pixar animated film Coco!) And so Douglas realizes, and tries to write down, “I, Douglas Spaulding, someday must…” but can’t finish it.

In between, much of the book describes incidents that do not involve Douglas. Grandpa harvests dandelions from the lawn and makes wine, for the family to sip throughout the next winter; a boarder offers to plant a type of grass that doesn’t need cutting, and suffers Grandpa’s wrath (a typical RB rant against ‘progress’); a man tries to invent a “happiness machine”; two little old ladies drive an electric car and worry they’ve killed a neighbor.

The ‘happiness machine’ episode involves a man obsessed with building a device to provide true happiness, that turns out to be a box that displays scenes and plays music from the most wonderful examples in existence. (It reminds me of the Edward G. Robinson death scene in the film Soylent Green, with scenes of gorgeous scenery and music by Beethoven.) But his machine malfunctions, and he concludes that true happiness is accepting what is stable, not transitory or easily forgotten, and that stability is looking at one’s household of wife and children, his family. It’s a typical RB statement of true verities.

Another incident is about an elderly woman, who saves every receipt and ticket stub, who is visited by children who can’t believe that she really was ever a girl, or even that she has a first name, and think her childhood photos were of someone else. At first disconcerted, the old woman comes to respond by admitting this is in some way true; and so she burns all the souvenirs of her past, and allows to the children that she was never pretty, or has a first name.

Another: a friend of Douglas’s, John Huff, announces his family is moving away to another town, and they’re leaving tonight. The boys play one last game of “statues,” during which John takes the opportunity to leave. And Douglas, heartbroken, decides he hates John Huff.

And there’s even a serial killer episode, concerning several elderly ladies who walk across the town’s ravine to see a movie, despite rumors of the “Lonely One,” who’s apparently killed a couple other women. Sure enough they find a woman, just murdered, and summon the police, but then attend their movie anyway. Later one of them, Lavinia, returns to her home, locks her door, and then realizes someone is inside the room with her— The end.

(This episode, “The Whole Town’s Sleeping,” was first published in 1950; in 1954 RB wrote a companion piece, told from the man’s POV, though the resolution is different than what’s [later! In 1957!] implied in DW. “At Midnight, in the Month of June” and the earlier story were both published in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine in 1954; this other story was reprinted in The Toynbee Convector in 1988.)

There are one or two sections that do have some fantasy content. The most obvious is the section about Elmira Brown, who thinks she is the target of a neighbor, Clara Goodwater, whom she suspects is a witch, especially since Elmira’s postman husband Sam reports that Clara has ordered books about becoming a witch. Elmira has suffered many misfortunes, including general clumsiness, and has failed, time and time again, to become president of the Ladies Lodge. In the finale of this story, Elmira concocts a potion to counteract the witchcraft, but collapses on stage, upon which Clara repents – and pulls the pins out of her Elmira doll.

The second fantasy item concerns a “Tarot Witch” at a local carnival, which dispenses fortune cards. Doug and his brother Tom get a blank card, which they decode, via flame, to reveal a hidden lemon juice message, which is “secours” – “help”. The boys try to “rescue” her and are outwitted by the manager, who throws the Tarot Witch doll into the ravine.

And maybe there’s a bit of fantasy in a late episode in which Douglas falls into a fever, and the town junkman brings round some bottles of water, grandly described, which heal Douglas by morning.

*

It’s necessary at some point to discuss Bradbury’s prose style. It wasn’t consistent across all his works, but in the stories closest to his heart, his style was his most recognizably florid and breathless. And his characters typically speak as Bradbury writes — In this sense, if in no other, RB is like Rod Serling, who also wrote speeches for his characters in long paragraphs of prose utterly unlike the way actual people speak. RB’s style was more restrained in other tales, e.g. the Mars stories, but especially in the Green Town stories of DW, and in the other stories that responded to his personal experience – the Ireland and Mexico stories, the Hollywood stories – he orated, he expounded, as if bursting from within at the glory of the world and passion of his beliefs.

Here’s a typical passage (not searching for an extreme passage, just a typical one), near the beginning of DW, as Douglas, his dad, and his brother, wander in the woods:

And he was gesturing up through the trees above to show them how it was woven across the sky or how the sky was woven into the trees, he wasn’t sure which. But there it was, he smiled, and the weaving went on, green and blue, if you watched and saw the forest shift its humming loom. Dad stood comfortably saying this and that, the words easy in his mouth. He made it easier by laughing at his own declarations just so often. He liked to listen to the silence, he said, if silence could be listened to, for, he went on, in that silence you could hear wildflower pollen sifting down the bee-fried air, by God, the bee-fried air! Listen! The waterfall of birdsong beyond those trees!

This is pretty good – but a little of this goes a long way. You get used to it, and calibrate your reception of this prose to follow the story, sometimes despite what can seem excessive, even obscuring. At times this rapturous, poetic prose verges on the ungrammatical; you can read entire long paragraphs without quite understanding what is supposed to be going on. I’ll provide some of those examples in future posts.

Here’s another passage, about those water bottles that heal Douglas’ fever:

Derived from the atmosphere of the white Arctic in the spring of 1900, and mixed with the wind from the upper Hudson Valley in the month of April, 1910, and containing particles of dust seen shining in the sunset of one day in the meadows around Grinnell, Iowa, when a cool air rose to be captured from a lake and a little creek and a natural spring. Now the small print… Also containing molecules of vapor from menthol, lime, papaya, and watermelon and all other water-smelling, cool-savored fruits and trees like camphor and herbs like wintergreen and the breath of a rising wind from the Des Plaines River itself. Guaranteed most refreshing and cool. To be taken on summer nights when the heat passes ninety.

*

Finally, though: about this book, DANDELION WINE. As I mentioned earlier, I’m rereading some of my favorite sf/f authors, in part to revisit that golden age when I was 12, and in part to reconsider what I think science fiction means, what it’s about, after 50 years of reading it.

There’s no science fiction in DANDELION WINE – but there are stories that reveal Bradbury’s attitude about change, about technology. The “Happiness Machine” episode is one: the device is unnecessary and destructive, since true happiness lies in the verities of family. The “Green Machine” episode is another: two old ladies try out new technology, but it’s dangerous and uncontrollable. The “Lawns of Summer” episode suggests that the conveniences of technology (grass that doesn’t need cutting) aren’t worth the loss of traditions.

Bradbury famously said “I don’t try to describe the future. I try to prevent it.” (https://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/ray_bradbury_124755)

And so did Bradbury write science fiction? Or some illegitimate counterpart? (In those nonfiction anthologies from the 1950s that I blogged about late last year, Bradbury was noted as an exception to the general rule for how science fiction should be rigorously scientific.) Yes, he did. Bradbury, to this day, is recognized as a major science fiction author, and I don’t want to fall into the “No True Scotsman” fallacy of thinking that a recognized science fiction author didn’t really write science fiction, according to some private definition. Yes, Bradbury wrote science fiction, especially in THE MARTIAN CHRONICLES and FAHRENHEIT 451, as I’ll explore in future posts. And my job is to understand what science fiction really means, and is about (as opposed to fantasy), in a way that accounts for Ray Bradbury.

*

One final tease: I’ve only realized during the past couple months of rereading Bradbury, that my own childhood, the places I grew up in, correspond rather remarkably to the three settings of RB’s key books: Mars, Suburbia, and Green Town. I need to post further family photos from my early life, the places I grew up, to justify this claim. Perhaps this is why, despite my relatively hard-nosed attitude about science fiction vs. fantasy, I still feel a deep affection for the works of Ray Bradbury.

*

Wait, one more tease: I’ll follow up on RB’s oddly remarkable sequel to DANDELION WINE, FAREWELL SUMMER, in a separate post.