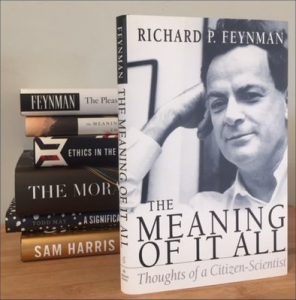

Here’s a short book of three essays first delivered as lectures at the University of Washington in Seattle, in 1963, gathered into a book published in 1998. Feynman, of course, was a famous CalTech physicist influential for work in quantum mechanics, inventor of pictorial diagrams to describe the behavior of subatomic particles that later became known as Feynman Diagrams. He won the Nobel Prize for his work in quantum electrodynamics.

Here’s a short book of three essays first delivered as lectures at the University of Washington in Seattle, in 1963, gathered into a book published in 1998. Feynman, of course, was a famous CalTech physicist influential for work in quantum mechanics, inventor of pictorial diagrams to describe the behavior of subatomic particles that later became known as Feynman Diagrams. He won the Nobel Prize for his work in quantum electrodynamics.

This book is subtitled “Thoughts of a Citizen-Scientist,” and the lectures addressed a lay audience, not an audience of fellow scientists or of students.

My quick take: Feynman addresses issues of science, religion, and public credulousness that are all too familiar; not much has changed from 1963 to 2018.

The first lecture, “The Uncertainty of Science,” reviews the idea of science in three aspects: as a method, as the content of its results, and as what it can produce, i.e. technology. In the method, “observation is the judge of whether something is so or not,” and exceptions test, or ‘prove,’ the rule. Science requires objectivity, and thoroughness. The more specific a rule, the better. It doesn’t matter where ideas come from, or the background of any individual scientists; relations among scientists are good. Imagination is important, yet it’s difficult to imagine something truly new, that’s consistent with all past rules and observations. Why to the laws of science change? Only when the ‘sieve’ becomes smaller. Some uncertainty always remains; doubt is not to be feared. When people wonder how one can live without certainty, Feynman responds, “how you get to know is what I want to know” p28.0

The second lecture is “The Uncertainty of Values.” We must admit we don’t know the meaning of life; the worst times of history have been when “people who believed with absolute faith and absolute dogmatism in something. And they were so serious in this matter they insisted that the rest of the world agree with them. And then they would do things that were directly inconsistent with their beliefs in order to maintain that what they said was true.” p33-34.

And so he talks about religion, reflecting on how students come to university (i.e. CalTech) and gradually give up belief in their fathers’ God. Most scientists don’t believe. Why? They most plausible idea is reflection upon learning the facts of the universe: its size, the relationship of man to animals, and so on; “Can the rest be just a scaffolding for His creation?” These scientific views “appear to be so deep and so impressive that the theory that it is all arranged as a stage for God to watch man’s struggle for good and evil seems inadequate” p39.8.

And yet moral values are not affected by loss of religious belief; they are thus independent. Yet he admits that Western civilization has two great heritages: the adventure into the unknown, and Christian ethics, and that the latter remains the source of inspiration.

(And then he trails off into a discussion of Russia and US, how the US government isn’t great, but it’s better than any other, and how Russia is backward, with discussions about Lysenko and others, and how governments should never impose any answers.)

The third lecture, “This Unscientific Age,” is a ramble in which Feynman admits he covered his planned topics in the first two lectures. So here he discusses various “uncomfortable feelings” he has about the world. Though we live in a scientific age, how few people understand even the basics of science. (It’s always been so, was my thought.)

He discusses ‘tricks’ about how to judge an idea. People who have quick answers to complex problems are dishonest — most politicians. Uncertainty again, and how we can be pretty sure about many things without being absolutely certain. E.g., how to test a supposed mind reader, at Las Vegas resorts; how experiments reading cards [he’s referring to J.B. Rhine, notoriously known a few decades ago and now mostly forgotten] became less impressive as tests were refined; how in contrast hypnotism turned out to be valid.

Flying saucers: ordinary people argue about what’s *possible*. That’s not the point; it’s whether the idea of alien spacecraft is *probable*. How the Catholic Church goes about proving a saint. How an anecdote, or one or two occurrences, prove nothing; “Otherwise you become one of these people who believe all kinds of crazy stuff and doesn’t understand the world they’re in. Nobody understands the world they’re in, but some people are better off at it than others.” p84

Some problems are due to lack of information, e.g. astrology, prayers, faith healing, Biblical prophecy: “I think it just belongs to a general lack of understanding of how complicated the world is and how elaborate and how unlikely it would be that such a thing would work.”

He visits a John Birch Society center in Altadena, which promotes tenants about “ancient principles of warfare” such as the 10th, paralysis, which the host claims is behind so much wrong in the world. It’s like paranoia; it’s impossible to disprove. Again, Feynman says, it’s about a lack of a sense of proportion. “And so it is with these people. They don’t have a sense of proportion.” p105. He humors the host by agreeing with her, to absurdity. (It’s very 2018.)

And he trails off discussing radiation from nuclear tests, the Mariner and Ranger probes, where scientists get their ideas from, Arabic science in the Middle Ages, the chaotic spelling of English, the many non-technological advances of man [i.e. humanity] such as economic systems, accounting, laws, and government organizations, future potentials of fusion and biology, and how he admires the encyclical of Pope John XXIII (i.e. what’s known as Vatican II]

\\

My takeaway from this book is his recurring thought that much gullibility about pseudoscience (and religion) is based on “a general lack of understanding of how complicated the world is and how elaborate and how unlikely it would be that [any such thing] would work.” A lack of a “sense of proportion.”

This aligns with the past three posts, about the value of education, about how the religiously-home-schooled teenager in Equus had nothing real to base his worldview on, and about the susceptibility of some to conspiracy theories and intuitive physics.

I’ve been thinking of the word ‘savvy’ as the quality of having this “sense of proportion” and this “understanding of how complicated the world is,” and, currently, the added understanding of the cognitive biases that have been identified in the past couple three decades, which cause one to reassess anything one might ‘believe’ to think about why such a belief might be held, as opposed to whether it is a valid belief, or understanding, of the world as it actually exists. I’ll be developing this theme.

\\

Richard Feynman

Feynman diagram

Simple English Wikipedia: Feynman diagram

Second Vatican Council