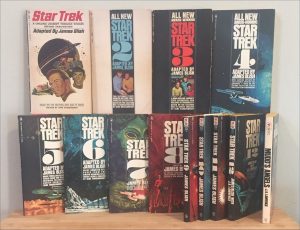

In January 1967 – only four months after the show debuted on NBC – Bantam published STAR TREK, by James Blish, a noted science fiction writer since the early 1950s and winner of a Hugo Award for the novel A CASE OF CONSCIENCE. The book consisted of seven short stories, each based on an episode of the series. A second book followed in February 1968, with eight stories; a third in April 1969, with seven stories. While the first two books contained stories from 1st season episodes, the third had six from the 2nd season and one from the 3rd. The fourth book came in July 1971, with stories from all three seasons of Trek. The next four books were all published in 1972, and then three more books came in ’73, ’74, and November 1977, by which time Blish had died, so that the final book was finished by his wife, J.A. Lawrence. A final book, MUDD’S ANGELS by Lawrence alone, appeared in May 1978, containing two episodes about Harry Mudd, from the 1st and 2nd seasons, with the second half of the book being an original story by Lawrence about Harry Mudd.

In January 1967 – only four months after the show debuted on NBC – Bantam published STAR TREK, by James Blish, a noted science fiction writer since the early 1950s and winner of a Hugo Award for the novel A CASE OF CONSCIENCE. The book consisted of seven short stories, each based on an episode of the series. A second book followed in February 1968, with eight stories; a third in April 1969, with seven stories. While the first two books contained stories from 1st season episodes, the third had six from the 2nd season and one from the 3rd. The fourth book came in July 1971, with stories from all three seasons of Trek. The next four books were all published in 1972, and then three more books came in ’73, ’74, and November 1977, by which time Blish had died, so that the final book was finished by his wife, J.A. Lawrence. A final book, MUDD’S ANGELS by Lawrence alone, appeared in May 1978, containing two episodes about Harry Mudd, from the 1st and 2nd seasons, with the second half of the book being an original story by Lawrence about Harry Mudd.

As far as I know books of adapted scripts like these were unprecedented. Certainly there were other original books published in that era, the mid-1960s, that tied-in with existing TV shows or movies, and some were by noted SF authors. There were two TIME TUNNEL novels by Murray Leinster, who also did three LAND OF THE GIANTS novels; there was a LOST IN SPACE novel by Dave Van Arnam and Ron Archer, there were two books by Keith Laumer based on THE INVADERS (with a third by Rafe Bernard). But these were all original stories, based only very loosely on the TV series and not adapted from particular scripts. There was even a Trek novel like this, by Mack Reynolds, called MISSION TO HORATIUS, but it was published for kids and no one cared.

In contrast, Theodore Sturgeon did a reportedly faithful adaptation (I haven’t read it) of Irwin Allen’s TV movie VOYAGE TO THE BOTTOM OF THE SEA in 1961, that explicitly credits the original screenplay.

Similarly, James Blish’s STAR TREK books contained stories based on specific episodes of the series, and each book dutifully credits the scriptwriters of those shows.

Blish’s stories were adaptations, though, not transcriptions, and while the plots and much of the dialogue from the episodes is kept intact, some scenes are omitted or condensed, so that a story seen on TV that lasted 52 minutes becomes 15 to 20 pages of print. Blish sometimes changed the story titles (“The Man Trap” became “The Unreal McCoy”) and sometimes the stories resolved quite differently than the TV episode originals (“Operation—Annihilate!”).

As the books went on the story versions got longer, 25 pages or more, with the stories in ST11 and ST12 running 35 to 40 pages each. And by about mid-way through the series the adaptations got much more literal, with only minor changes in dialogue or plot from the broadcast scripts, and the final books included much internal monologue revealing (sometimes questionable) character insights.

For years I had assumed that Blish, as a professional science fiction writer, took liberties with the earlier scripts he adapted to make them better science fiction stories, and that over the years he restrained those impulses to give readers what they wanted – as close to literal print versions of the episodes they had seen years ago, perhaps only in syndication. Several of the stories in the first couple books did seem noticeably improved from their script sources, while as noted by the midpoint in the series they stayed more literal. Blish even thought this was an improvement: in a preface to ST9, Blish writes, “From ST 6 on, I’m greatly indebted to Muriel Lawrence, who began by doing a staggering amount of typing for me, and went on from there to take so much interest in Star Trek itself that her analyses, suggestions, and counsel have made the adaptations much better than they used to be.” And ST11 is dedicated “to Muriel Lawrence for labors in the vineyard.”

Hmm. Only in the past couple of years, first by reading Marc Cushman’s books about the production of the show, and more recently by rediscovering that ST9 preface and figuring out who Muriel Lawrence was, have I understood what went on to produce the books that got published.

First, the primary reason stories in the first couple books varied from their broadcast sources is… that Blish was often sent preliminary versions of the scripts. As Cushman’s books detail, scripts often go through many versions, over weeks or months, from outline to first draft to drafts revised by the producers, with some changes made during filming and never even captured in script form. Apparently in 1966 and 1967 the studio, Desilu, was blasé about which script versions they packed up to ship to Blish (who was living in New York at the time). And so Blish worked with what he had.

Second, Blish took the job of doing adaptations of the show for Bantam Books for the money. He didn’t care about the show, and regarded the job of adapting someone else’s material as hackwork that would possibly be damaging to his career. He did it anyway, but he didn’t bother to watch the show. To correct an assumption I made elsewhere, Blish wasn’t living in Britain when the show was broadcast in the US, though he did relocate to Britain in 1969; he was living in the US and just didn’t bother to watch the show.

This page, https://memory-beta.fandom.com/wiki/James_Blish, at fan site Memory Beta, makes that point.

The fact is that until April, 1969, Blish lived in the United States, and if he had never seen Star Trek, it was because he didn’t want to.

Third, which I just discovered this week, Blish apparently didn’t actually write the Trek books himself past ST 5. The Memory Beta page also quotes a book about Blish — a book I don’t have, but which can be seen on Amazon (https://www.amazon.com/Imprisoned-Tesseract-Life-James-Blish/dp/0873383346/) by SF scholar David Ketterer, thus:

“Blish, in Josephine Saxton’s words, ‘affected to despise Star Trek‘ and, in fact, he had not written Star Trek 10. Judith Blish has revealed that Star Trek 6-11 (all of which appeared under Blish’s name except the last where J. A. Lawrence appears as collaborator) were essentially written by Judith Blish and her mother Muriel Lawrence.” (Ketterer; 25)

So–! Apparently Blish farmed out the task of cranking out Trek books – remember how four came out in 1972 alone? – to his wife and mother-in-law! It might be noted that Judith Ann Lawrence Blish never published any work of her own, beyond the Trek books that credited her.

Oddly, there are infelicities of description and word choice in the adaptations in the late books that makes one wonder whether Lawrence and her mother had ever actually seen the show, either. Those details are in the individual posts.

\\\

Finally, with that background in mind, some generalizations about the Trek books can be summarized, thus:

- In the early books by Blish, stories are told from a single point of view, Kirk’s, so that broadcast scenes where Kirk was not in the room are simply omitted or at best summarized as context.

- Blish worked from scripts that were often not final drafts, so that in some cases the outcome of the story is quite different from the broadcast version, an extreme example being “Operation—Annihilate!”

- Blish did improve some of the stories with his own science fictional and scientific expertise (he studied microbiology and zoology), a good example being in “Miri,” in which the description of the development of a disease cure is much more elaborate than in the broadcast version.

- The later books by Lawrence & Lawrence stay more closely to the source scripts than Blish’s did, and generally present every scene from the source scripts (whether Kirk was there or not). These adaptations are therefore on average longer than Blish’s. Still, there are variations in dialogue wording in most, as if they too did not always receive final script drafts, or had no way of knowing what changes were made during production that weren’t reflected in the script. The interest in the later adaptations is to find lines of dialogue, and sometimes entire scenes, that were presumably scripted but not shot, or shot and then edited out for time.

- Evidence suggest that neither Blish nor his wife and mother-in-law were familiar with the show from actually seeing it, given various infelicities in the texts.