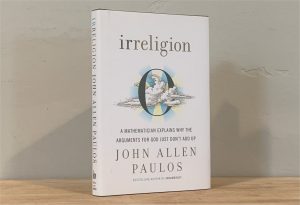

John Allen Paulos, Irreligion: A Mathematician Explains Why the Arguments for God Just Don’t Add Up. Farrar, Straus and Giroux/Hill and Wang, 2008.

John Allen Paulos is a professor of mathematics who’s become, over the past three decades, well-known as an author who applies basic mathematical reasoning to everyday topics. His first hit was Innumeracy: Mathematical Illiteracy and Its Consequences (1988), exploring how misconceptions about math, especially statistics and probability, leads to errors in public policy and personal decisions. A later book, A Mathematician Reads the Newspaper (1995), extended the theme. (Understanding basic mathematical ideas like these and applying them to everyday things is part of my general concept of being “savvy.”)

The book here, slender and breezy, applies mathematical reasoning and simple logic to the various arguments for the existence of God, and finds those arguments wanting (of course). Appearing in 2008, this book can be seen in the context of the various “new atheism” books by Harris, Dawkins, et al, that appeared in the mid-2000s. There was obviously an audience for books that dismantled the presumptions of religious faith.

Brief Summary:

- Four classical arguments for the existence of God are examined and dismissed for logical incoherence and/or statistical implausibility: arguments from first cause, from design, from the anthropic principle, from ontology.

- Four subjective arguments, from coincidence, prophecy, subjectivity, and interventions, are dismantled on statistical grounds.

- And four Psycho-Mathematical arguments — on redefinition, cognitive tendency, universality, and gambling — are also dismantled.

- With asides about a personal pseudoscience, recursion, emotional need, Jesus and CS Lewis, a dream conversation with God, and the idea of “brights.”

Detailed Summary: [[ with comments in brackets ]]

Preface

This book addresses if there are logical reasons to believe in God. (Author is droll: “There are many who seem to be impressed with the argument that God exists simply because He says He does in a much extolled tome that He allegedly inspired.”) Author claims an inborn materialism—that matter and motion are the basis of all that there is. Recalls adolescent skepticism about Santa Claus, and God—what caused or preceded him?. The inherent illogic to all arguments for the existence of God are addressed here. The book will be informal and brisk, with no equations. Author always wondered about a proto-religion for atheists and agnostics that would still acknowledge the wonder of the universe: the “Yeah-ist” religion, “whose response to the intricacy, beauty, and mystery of the world is a simple affirmation and acceptance: Yeah.”

Four classical arguments—

The Argument from First Cause (and Unnecessary Intermediaries)

Argument: Everything has a cause; nothing is its own cause; there had to be a first cause; call it God.

The problem here is the first assumption—either everything has a cause, or it doesn’t. If the former, God has a cause too; if the latter, why invoke God?; maybe the universe itself has no cause. Related is the natural-law argument, that something must have caused the particular natural laws we see in the universe.

The very notion of cause has its problems. And perhaps the assumption that nothing is its own cause is the problem.

[[ the other problem with arguments like this is that, even if valid, what does the ‘god’ of this argument have to do with any particular conception of what god is? ]]

The Argument from Design (and Some Creationist Calculations)

Argument: The universe is too complex (or beautiful) to have come about by accident; it must have been created; thus God exists. (Alternatively, the universe seems to have a purpose; thus God.)

Example of William Paley and the watch on the beach.

The problem with this argument is knowing what’s ‘too’ complex to come about randomly. In any event, wouldn’t the creator be even more complex in order to have created the universe? Who created the creator’s complexity? It’s a metaphysical Ponzi scheme. Like a mnemonic more complicated than what it’s designed to remember. In contrast, we have a well-confirmed explanation for the origin of life’s complexity: evolution.

Those opposed to evolution who cite calculations of improbability of a given occurrence (like the eye) miss the point. The argument is deeply flawed; any particular development is unlikely, just as any particular arrangement of a shuffled deck of cards is unlike. Then there is Michael Behe’s irreducible complexity, applied to, say, the clotting of blood. Again, such complexity is explained by evolution; yet those who reject evolution are immune to such explanations.

Further, we can compare evolutionary matters to free-market economies—were those economies set into place, someone determining every rule in advance? Of course not; the system emerged and grew by itself. Odd that opponents of evolution usually support free-markets—they reject the idea of central planning (yet presume such central planning by the omniscient creator). So too does software like the game of Life and Wolfram’s cellular automatons show how simple rules result in great complexity; these ideas are not new. Someone who claimed the economy was the result of a detail-obsessed, all-powerful lawgiver might be thought a conspiracy theorist.

A Personally Crafted Pseudoscience

Digression. To anticipate the following arguments: Take any four numbers associated with yourself—height, weight, birth date etc—and consider various powers and products of them. (It’s straightforward to set up a computer program to generate thousands of combinations of product and factors, etc.) It’s likely that some of these combinations will be close to the speed of light and other such universal constants—especially if you juggle units. Does this imply you have a personal relationship with creation?

The Argument from the Anthropic Principle (and a Probabilistic Doomsday)

Argument: the physical constants are such that if they were slightly different, humans wouldn’t exist; humans exist; so those contants must have been fine-tuned by God.

Well, maybe other creatures would exist if the constants were different; one can’t know. There may be many universes, each with different laws and constants.

Related is the phenomenon of self-selection, applied to the Doomsday argument—example to judge why doomsday, that might happen anytime, should happen in any particular person’s lifetime.

The Ontological Argument (and Logical Abracadabra)

Examples of this go back to Plato’s Euthydemus. This concerns paradoxical, self-referential statements. e.g., If this statement is true, then God exists. Such statements can be used to prove, or disprove, anything.

Argument: The classic argument is that by definition God is the greatest and most perfect being; it’s more perfect to exist than not; therefore he exists.

The same argument could prove that a perfect island exists. Hume observed the only way words can prove anything is where a contradiction can be shown, e.g. that God is both omnipotent and omniscient. But no such disproof of God’s existence is possible.

Self-recursion, Recursion, and Creation

Digression: Recursion is a powerful concept key to computer programming. Examples are virus-like; example of Pete and repeat. Or von Neumann’s recursive definition of positive whole numbers. A lot of religious arguments are similar. If you assume a false thesis, you can prove anything.

Four Subjective Arguments—

The Argument from Coincidence (and 9/11 Oddities)

As in The Celestine Prophecy [a bestselling book]: coincidences impress some as evidence of God. The assumption is things don’t happen by accident; everything happens for a reason, etc.

Examples relate to 9/11—all sorts of numerical derivations. But of course you can do similar things with any date or set of words. Verses attributed to Nostradamus relating to 9/11 were simply made up. Photos were circulated on the internet.

People look for patterns and see them whether they’re there or not. People remember positive examples and forget counterexamples. What are the odds of some uncanny coincidence occurring? Quite high—there are so many potential events. A passage from Clarke’s Rendezvous with Rama told of a fireball on Sep 11th, 2077…

[[ there’s also the point of *why* coincidences would mean anything to anyone; there’s a psychological undercurrent that no one ever seems to discuss ]]

The Argument from Prophecy (and the Bible Codes)

Of course, some prophecies from holy books come true, but not enough of them to mean anything. Oddly, the more details a holy book contains, the less likely they might *all* be true, no matter than people ‘accept’ the book as true. Just because it’s in the Bible doesn’t close the matter; just because a holy book claims it’s true doesn’t make it true. People who think it does sometimes resort to the argument from red face and loud mouth.

Biblical codes concern equidistant letter sequences (ELSs), the way ‘nazi’ is within ‘generalization’. The discovery of rabbi names, etc, in the Torah was taken as proof of divine inspiration. True, the calculated probability of a particular ELS is tiny; but the discoveries weren’t predicted; they could have been anything. The likelihood of *some* interesting ELS *somewhere* is pretty high.

An Anecdote on Emotional Need

Digression: Author recalls helping three Thai girls, on Xmas day in 2006, dupe online boyfriends for cash, and considers how desperate those remote boyfriends wanted to believe in their girlfriends is like the intense need people have to believe in God. Author doesn’t believe in God, but doesn’t want to scoff at emotional need.

The Argument from Subjectivity (and Faith, Emptiness, and Self)

It’s hard to address the argument that people simply feel that God exists in their bones, or wherever. Similar is the argument that the idea there isn’t a God is too depressing, therefore there is. But there’s no way of verifying such subjective insight—unlike the way a blind person might verify the directions given him by a sighted person.

Similar is the argument that since all worldviews are valid, god exists. It would be arrogant for an agnostic to belittle someone’s religious beliefs, but usually it’s the believers who attacks the nonbelievers. How would an argument for theism work, to justify particular creeds? Belief in god doesn’t imply divinity of Jesus.

After all, most people are atheists about others’ gods. Atheists and agnostics just go them one better.

Even more absurd is to claim the existence of a personal god who answers prayers, intervenes with miracles, etc., which presumes an overweening sense of self-importance. [[ And yet my impression is that this is by far the most common sort of belief in God! ]]

Even the idea of self is unstable; we are constantly changing throughout our lives.

[[ The reply to this whole line of thought is to realize that millions of people around the world have passionate, subjective feelings about *other* gods ]]

The Argument from Interventions (and Miracles, Prayers, and Witnesses)

Miracles demonstrate the existence of God? Stories of ‘miracles’ seem to be getting more press lately. But claims are inconsistent; a few saved is a miracle, millions dying is a natural disaster; aren’t both divine or not? A local case (in author’s home Philadelphia) involved a Mother Drexel and two children who prayed to her and recovered. The famous Fatima case, children who experienced prophecies that were so vague they could apply to anything. The idea of miracles is counter to the weight of science—a miracle would simply mean the scientific laws were wrong. And testimony, of course, is not dependable—delusion or lying is more likely than a miracle.

Remarks on Jesus and Other Figures

The popularity of Mel Gibson’s Jesus movie (The Passion of the Christ) suggests that many believe the existence of such figures prove God’s existence. But: we often know little about news stories that happen in full view; we realize that and suspend judgment. But not with distant historical events, such as the events of that movie, recorded in the New Testament decades after the fact. Consider the political situation at the time of J’s death. Compare to the death of Socrates. Would one blame contemporary Athenians on his death? Would a film about it one dwell on the agony of him being poisoned?

CS Lewis’ arguments were uncompelling—we don’t know what Jesus said, or if his story is accurate. The flaw in The Da Vinci Code (the popular book and then film, which presume to identify a modern-day descendant of Jesus) is that any given biological line (e.g. Jesus’) would likely either die out quickly, or grow so that millions could claim to be descendants after centuries. Given parents, grandparents, etc., going back 40 generations we would each have a trillion ancestors; so obviously they were not all different people. If anyone from 3000 years ago has any descendants—it would be all of us.

Four Psycho-Mathematical Arguments

The Argument from Redefinition (and Incomprehensible Complexity)

Some attempt to redefine God as something else—nature, the laws of the universe, mathematics. This may be one reason many people say they are believers. God is Love. Or God is simply incomprehensibly complex. This is equivocation. The theory of everything may be beyond the complexity horizon. Yet nothing can be so complex that patterns aren’t apparent at various levels, enabling descriptions of order—inevitably. And in sufficiently large populations or sets, certain lower-level properties are guaranteed; examples of people at dinner parties who do know or do not know each other. Recall Stuart Kauffman’s work on self-organization. Claims these phenomena prove God are very strained.

The Argument from Cognitive Tendency (and Some Simple Programs)

Some say the fact that cognitive biases and illusions exist as proof of what they perceive, e.g. God. People have an inborn tendency to search for explanations and intentions. E.g., a thought experiment about a man’s car; or why extraordinary causes seem necessary to explain the deaths of JFK or Diana, to say nothing of the universe.

And we seek confirmation more anxiously than disconfirmation; we can be blind to contrary facts. The source of perpetuating stereotypes.

The ‘availability error’ is the inclination to view anything new in the context of what is already known—war, scandal, religion. Thus, other religions confirm the existence of God! The reason most people adopt their parents’ religion—cultural traditions. “…religious beliefs generally arise not out of a rational endeavor but rather out of cultural traditions and psychological tropes.” Children are no more Catholic because their parents are, than they are, say, Marxist because their parents are.

The last is the notion that ‘like causes like’. Complex results must have complex causes. But some computer examples (fractals) show that simple rules create complex results. Stephen Wolfram’s book A New Kind of Science, e.g. his rule 110 (page 112). Very simple rules result in patterns similar to those in biology and other sciences. Wolfman suggests simple programs might capture scientific phenomena better than equations. [[ this is a profound points, I think. ]] [[ there’s also the entirely subjective notion of what is ‘complex’ vs ‘simple’ ]]

My Dreamy Instant Message Exchange with God

Author had a dream conversation with God, who claims he evolved from the universe’s biological-social-cultural nature.

The Universality Argument (and the Relevance of Morality and Mathematics)

That the moral sense of different cultures is similar is taken as being instilled by God. Though this doesn’t explain blasphemers, criminals, homosexuals, etc. [[ if instilled by God, why aren’t they as invariant as the biological processes of staying alive? ]] Anyway, evolutionary forces explain why moral codes are similar in cultures that survive for long. (cf. Marc D. Hauser’s book—another group theory argument.) Also, if moral laws aren’t arbitrary, then their goodness is true without their being a god.

That leads to the old problem of why God would allow evil to exist; the usual answer, that we don’t understand his ways, explains nothing. And the many other obvious childlike notions in religious doctrine. The Boolean satisfiability problem is about determining if a set of statements, true or not, are consistent. Most sets of religious beliefs are inconsistent.

Scientists have long wondered about the universality of science and math. Is the fact that math works to explain the world really mysterious? Our ideas about math derive from interaction with the physical world. Counting, arranging, then abstracting. Evolution has selected those of our ancestors whose behavior and thought were consistent with the workings of the universe.

The Gambling Argument (and Emotions from Prudence to Fear)

Pascal’s wager applies to any religion, of course. And trying to assign probabilities to God’s existence is a futile task. Statements using ‘is’ are subject to linguistic confusion.

The wager isn’t much different than believing in god just because the idea of dying is dreadful. It’s similar to rallying around a leader in dangerous times. Dick Cheney’s one percent doctrine: even a 1% chance of there being weapons of mass destruction justifies war.

Anyway, there’s no evidence that nonbelievers are less moral or law-abiding. In a sense, moral acts by nonbelievers are more moral than those by believers who act to gain some divine reward.

Still, these arguments fail to persuade those whose critical faculties are undermined; and the untruths underlying faith make life more bearable to some.

Atheists, Agnostics, and “Brights”

Despite all this, atheists are the least tolerated minority in the US. Maybe what’s needed is a popular story or film, ala Brokeback Mountain. Another idea is to use a new term—maybe ‘bright’ (as proposed in the 2000s). Or at least greater acceptance of the admission of being irreligious. Author isn’t fond of the word bright. Yet hopes that as more people admit to being irreligious, to give up on divine allies and tormentors in favor of being humane and reasonable, the world would be a bit closer to a heaven on earth.