Here we are at the middle of May, some seven or eight weeks in to stay-at-home orders here in the Bay Area – when it started, my partner began working from home, except for the one day a week he would go in to work, his site’s senior staff alternating days to be on site. His first day working from home was March 17. For the next five weeks I suspended reading of books entirely. Things were too unsettled and uncertain to allow for the indulgence of sitting down and turning inward into a book. It was much more important to pay attention to everything going on in the outside world. I’d started Brian Greene’s intriguing UNTIL THE END OF TIME, and left it suspended around page 30. Still there.

Instead, inspired by a New York Times article I linked on Facebook, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/24/arts/coronavirus-myst-nostalgia.html, about the comfort of replaying computer games from years past (the article writer’s childhood; my 40s and 50s), I did in fact, over five or six weeks, replay all the Myst games, including the associated Uru and Obduction. Well, not played; I followed walkthroughs posted on various online sites, to revisit the games’ environments, their beauty, without having to re-solve all their puzzles from scratch. And, well, I played RealMyst not the original Myst. The issue is that the early games in the franchise were what were derisively called “slideshow” games in which the player could move only to certain preordained positions or nodes. In Myst and Riven and Myst III the point of view at each node was fixed. By Myst IV you could at least swivel around from each node to see your surroundings in every direction… That was true of Myst V too. RealMyst, Uru, and later Obduction, were vast improvements: the player, using arrow keys, could move freely in any direction, look around from any spot.

I should set the context that I have never been a “gamer,” and in particular have never had any interest in “first-person shooter” games or racing car games or any games that involve competition with other players. I’m a solitary guy. In fact over the 30 some years since I bought my first computer—a genuine IBM PS/2 (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/IBM_Personal_System/2) for some $2000, in 1987—I’ve played various solitaire games in part out of compulsion and in part as a mechanism to distract my conscious attention while my deep mind ponders other things. This is a legitimate thing. In the ‘90s there was Tetris; later things like Minesweeper; more recently Microsoft solitaire card games, and especially, currently, Microsoft’s Wordamant, where I play every month’s map and every day’s Daily Challenge. The Myst games, of course, are another league entirely than the solitaire games that take a few minutes each per round.

The first Myst game came out in 1993 and I was given it as a gift, by my long-time friend Larry Kramer, in 1994, for my birthday. I had to buy a new PC – a Gateway desktop, in a huge tower – to play it. Four years later, in 1997 (as I was launching the initial Locus Online website), I had to buy yet another new computer to play Riven. Trying it on the Gateway caused it to hang whenever I came into a scene with one of those spinning domes. The new one was a HP 8175 PC (Pentium II 233, 48 meg RAM, 56K modem, 17” monitor)—note the modem, this was pre-wifi, and the careful attention to specs about random access memory. The only people who worry about such stat’s now, I gather, are the gamers, whose new adventures require greater and greater computer power and memory and sophisticated graphics cards. Oh, and those collecting large video or music files. (For later games, I once had to purchase new graphics card, or several times install updated graphic drivers.)

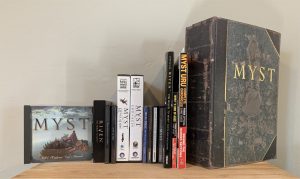

Over the following 20 years, I eagerly purchased each new Myst game as it was released. Here’s a photo of all the physical editions I have, from the first releases of all the games through Uru and Myst V (IIRC the Uru expansion packs were downloads), a “10th Anniversary DVD Edition” of the first three games, the three print guidebooks I have, and finally the recent Myst 25th Anniversary Collection, which I helped fund on Kickstarter, with versions of all the games that will run on modern computers, encased in a big box that mimics the “books” used in most of the games.

And since I keep records about everything, I’ll note the following:

- Myst, 1994, took me 10 days to complete

- Riven, 1997, two weeks

- RealMyst, 2001, was straightforward because it was the same puzzles as Myst

- Myst III, 2001, two weeks

- Uru, 2003, almost a month

- Myst IV, 2004, almost a month

- Uru expansion packs, 2004, 3 or 4 days each

- Myst V, 2005, four days

- Uru Live (online, the PC game with additional areas to explore), 2007; intervals over several months as new areas were released at intervals

- Obduction, 2016, two and a half weeks

- The Witness, 2016, almost a month

Keep in mind I had a day job in all these years (up to 2012), and since 2001 have had a live-in partner who disapproves of computer games, so I was only able to play them evenings, weekends, or on the sly. Yet, each time a new game was released, I was obsessed about it until finishing—I remember once I drove home from work at lunchtime because I’d had an insight into solving some puzzle, and needed to check it out immediately.

I’ve included The Witness here as the only game I’ve found over all these years that remotely approaches the beauty and complexity of the Myst games. I’ve tried others – e.g. Rhem, Schizm – but they pale in comparison, consisting mostly of convoluted puzzles without the underlying real-world sense of living places where, unfortunately, the power had been turned off (for example).

While all the Myst games involved a solitary player in some strange, bounded environment, having to solve puzzles of various types, they varied in the exact goal of the game-play, and the player’s interaction with other characters. Key points:

- All of the games involve one or more characters with whom the player interacts, or at least listens to. In the first game, game creators Robyn and Rand Miller played the three roles of Atrus, the man created Myst by writing a “linking book,” and his two crazy sons Sirrus and Achenar. (I’ve always thought it odd that these names are one letter away from names of bright stars in Earth’s sky.) In later games professional actors, some quite good, were brought in to play other characters: John Keston (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Keston) plays Gehn in Riven; Brad Dourif (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brad_Dourif) as Saavedro in Myst III; Juliette Gosselin as the girl Yeesha in Myst IV; David Ogden Stiers (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Ogden_Stiers) as Esher in Myst V.

- With the except of Uru, I think, all the Myst games offer multiple endings, one a successful or happy ending, the other or others unsuccessful or tragic ones. Which ending you reach depends on your interaction with the characters, usually about who you decide to trust. The ambitious player can save game progress at a key point, and restart it to take different paths each time to see all the endings.

- The games all have musical scores. As with the actors, in the first and second games one of the creators, Robyn Miller, did the music; after that professional composers, Jack Wall and Tim Larkin. While the music in the later games is slick, Miller’s music in the first remains the most iconic and haunting.

As game technology advanced, the manner of game-play changed from game to game, as mentioned above. Also, while the games all had similar puzzles to solve, there was usually something distinctive about each game.

- Uru’s game-play advances by finding and touching seven “journey-cloths” in each world, enabling return to the player’s central private island called Relto.

- Myst V you have a “slate” on which you can draw a shape or icon and then set the slate down on the ground; then when you step away from the slate, creatures called Bahro (as in Uru) approach the slate and interpret your mark and do something useful to solving a puzzle.

- Myst IV you can “touch” things with your cursor and hear the sound of what tapping each item would be. And certain objects trigger memories of a character’s interaction with that object.

- Myst III includes elaborate animations at the end of each age that take’s the player’s POV on some on a ride, on a trolley, back of a bird, or rollercoaster.

I will confess that I’ve never completed any of these games without searching out at least one hint. In the ‘90s game guides were published as trade paperback books, and I have them for Myst and Riven; since 2000 or so, when everything went online, there have been any number of sites that offer hints or walkthroughs or even YouTube videos showing how to solve every puzzle. I remember the exact point I got stuck in Myst: in the Mechanical Age there’s a control panel on top of an elevator, and the key to getting there is that you hit the “down” button in the elevator and then *step out* of the elevator in the brief interval before it starts moving. Then the control panel moves down and you can access it.

In contrast to the five Myst games, Uru was open-ended, with two “expansion packs” released a year after the original game to extend play and exploration of the underground city of the D’ni. Then the entire game went online, with additional areas added over a period of months in 2007. I played through some of those, but some of the “garden ages” required interaction between multiple players logged on at the same and able to interact. I found those annoying, as defeating one of the prime attractions of all these games: they were mysterious places one could explore privately. I didn’t want to have to interact with a bunch of strangers over the internet! Yet there were some intriguing differences between the main Uru games as installed on your PC, or accessible in Uru Online, so I did play most of the game online.

*

So do I have any favorite games or parts of games? Or anything I found relatively unpalatable or annoying? I think as I played them over the years, as they were released, I thought each new game was better in some way that the previous ones, if only because each had some new aspect of game play, or ways to interact with the environment. Yet I confess I never paid completely attention to the narratives behind the games—the rivalry between the boys, whey Gehn captured Catherine, and so on; and so the interruptions by Saveedro and Esher, the fragments of remembered conversations in Myst IV, were intrusions to be sat through. (There were two or three novels based on the games in the ‘90s; I never looked at them.) Perhaps that’s one reason I’ve replayed Uru, or parts of it, more often than any of the other games; after the introductory challenge by Yeesha, you’re off on your own, all alone.

I also look back more fondly on those games that were more than a hub world with three or four satellite worlds (or ages). Thus Riven, its ages more interconnected, and Uru, with its potentially indefinite collecting of new ages represented by books on you private home island in the sky Relto. I liked the music especially in the early games, and how the music enhanced the darker, moodier ages: Amateria in Myst III, Kadish Tolesa in Uru, Todelmer in Myst V, Kaptar in Obduction.

Fortunately a year or two ago I helped Crowdstart a 25th anniversary reissue of all the Myst games and Uru in versions suitable for modern computers. There was a long period, in the mid-2000s I think, when you couldn’t replay the original Myst or Riven, because they were incompatible with then-current operating systems.

And next is something called Firmament, https://fulfillment.fangamer.com/kindling/firmament, due some in 2020.

*

So since March 25th, when that NYT article appeared, I’ve played through, following online walk-throughs, all the games, including Obduction, with two exceptions. In Myst III I’m stuck at the same point I was originally, deep in Edanna near the glowing orchids, where you’re supposed to see a path through a rotting log in order to go further down. The game is too dark, the node movements too crude, and I can’t find the path down. And in Myst IV, I’m stuck at the monkey puzzle in Haven, with nothing happening when I spin the horns however slow or fast. Also I find the game-play interface most annoying in Myst IV; it’s nodal, and it’s slow, with a second or two pause after clicking before moving to the next node. So as I write, I’m paused at those points, but have finished the others all the way through.

Now maybe it’s time to get back to reading books.