Starman Jones is the 7th of 14 novels that Heinlein published from 1947 to 1963, at annual intervals except for a four-year gap between the last two, that were called “juveniles” at the time — that is, designed for younger readers — what are now called YA, for Young Adult, novels. (It’s worth noting that the 13th of these, Starship Troopers, is usually *not* considered YA, in the way all the others are, but that’s a topic for another time.)

I read most of these books in the early ’70s, before my 20th birthday, but I came to Heinlein later than I bonded with Asimov, Clarke, and for that matter, Bradbury. Over the decades my regards have shifted, though I still find myself rereading Heinlein after I’ve already, in the past five years, reread most of AB&C.

Starman Jones was one of my favorites, and this is the fourth time I’ve read it over 50 years. I suppose its appeal is the common adolescent fantasy of running away from home (especially from cruel parents), and achieving great success. Of course, the adult reader is more skeptical of such a plot than the teenaged one.

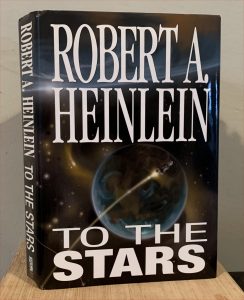

The edition I’m reading now is part of a Science Fiction Book Club omnibus, shown above, published in 2004.

Gist

In a future when starflight is common, as are high speed trains that run on suspended “ring roads,” teenager Max works on a farm run by his stepmother. When stepmother remarries — to a man who dares to sell Max’s books, left to Max by his uncle — Max rebels and runs away.

Through a series of fortuitous meetings, some with grifters, he finds a job on a starship, first as a low-level “spaceman,” tending passengers’ pets; then as a “chartsman,” when his eidetic memory, and knowledge of astrogation manuals, is discovered; and eventually, after a series of accidents and tragedies, is obliged to take over captaincy of the ship itself.

\\

Key Points and Quotes

- This is a story, like some Dickens’ novels, of incredible coincidences and handy talents. It’s not ‘realistic,’ but you go with it.

- I remembered, from the last time I read this 25 years ago, the broad story arc, but not the overlay over several chapters near the end on the alien planet. At first it seems like this entire episode is filler. But reading it now, its purpose is to maneuver Max into the position of having to take command of the ship — the ship can’t stay on the planet, because of hostile aliens; and the captain has died ignominiously, having made the mistake that stranded the ship in unknown space.

- As always Heinlein has experienced adults offer advice to the young protagonist, advice presumably aligning with Heinlein’s own views. At the beginning of Chapter VII, Sam notes to Max, “But you haven’t learned yet that when in Rome, you shoot Roman candles. Every tribe has its customs and what is moral one place is immoral somewhere else. There are races where a son’s first duty is to kill off his old man and serve him up as a feast as soon as he is old enough to swing it–civilized races too.” (I seem to remember this sentiment from Time Enough for Love, which I haven’t reread since 1973.)

- Near end of Chapter IX: how it suits guild politics to make their profession appear to be an arcane art, while in fact the knowledge is easily available anywhere. (In the novel, Max’s uncle was in the Astrogators’ Guild and had promised to elect Max, even though not his son, to the guild, and had left Max his astrogation guides. The guides are treated as rare books by the guild, but Max learns they contain knowledge easily available anywhere.)

- Chapter 1, second page: his Maw annoys him with “petty gossip when he wanted to read, or just as bad, be disturbed by the slobbering stereovision serials she favored.” (Remember this is 1953.)

- End of chapter 1: Heinlein makes a big point about library books: “…the theft of a public library book–or failure to return it, which was the same thing–was, if not a mortal sin, at least high on the list of shameful crimes.”

- In Chapter III Max and his hobo friend Sam order breakfast in a diner. Sam: “My partner and I will each have a breakfast steak with a fried egg sitting on top and this and that on the side. I want that egg to be just barely dead. If it is cooked solid, I’ll nail it to the wall as a warning to others. Understand me?”

- And another fortuitous event: Max attracts the attention of a wealthy young woman, Ellie, who pulls strings on his behalf at a couple key events.

- Heinlein offers a now-familiar rationalization for FTL travel, the one involving “folding” space, like a napkin, to bring two locations close together across another dimension.

- Chapter XIV: The ship having become lost in space, Max wonders if they’re even in the right galaxy, or universe. “He had read enough philosophical fancies to know that there was no theoretical reason for such to be impossible; the Designer might have created an infinity of universes, perhaps all pretty much alike–or perhaps as different as cheese and Wednesday. Millions, billions of them, all side by side from a multidimensional point of view. // Another universe might have different laws, a different speed of light, different gravitational ballistics, a different time rate…” This is sophisticated speculation that anticipates some modern cosmological theories. And it strikes me as unusual for Heinlein to invoke a ‘Designer.’