How racism persists while changing its expression; how cherry-picking the Bible has been done for centuries; and how the seven-day week has only recently become the worldwide standard.

Some things never change, 1.

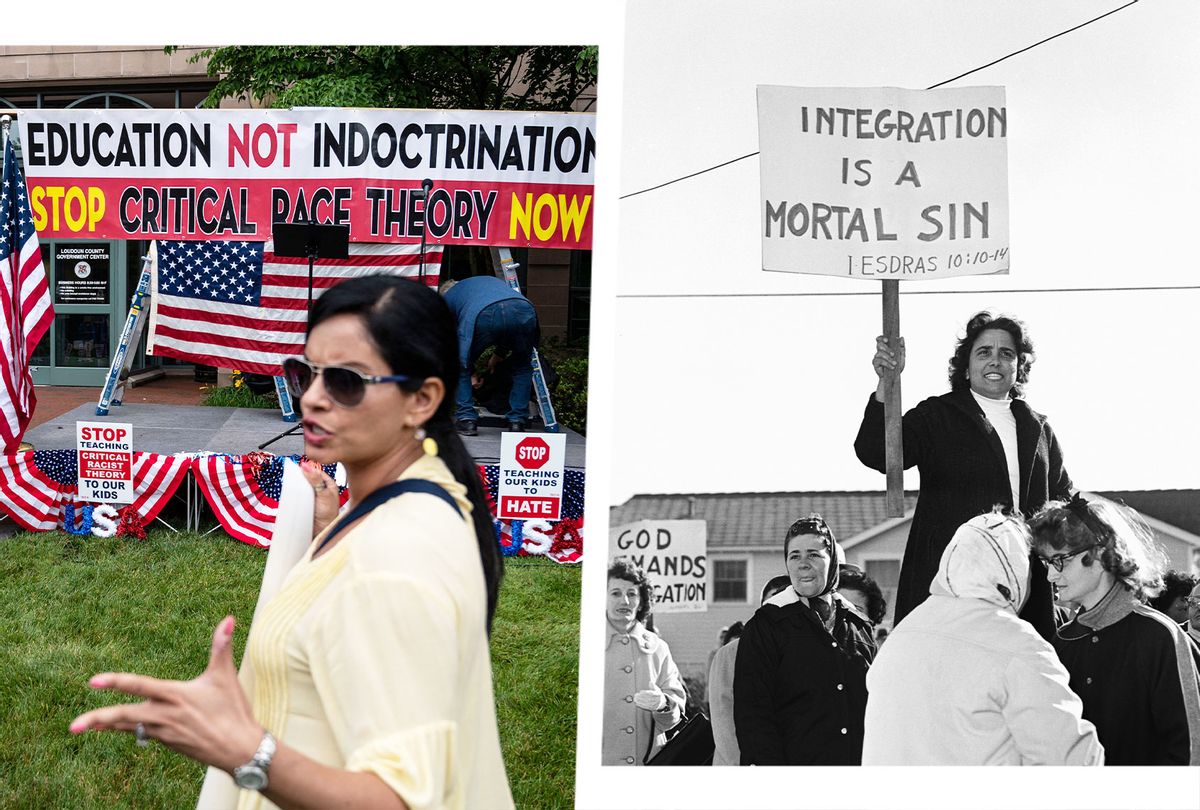

Salon, Chauncey DeVega, 16 Nov 2021: Right’s cynical attack on “critical race theory”: Old racist poison in a new bottle, subtitled, “White supremacy keeps rebranding itself — but the song remains the same”

The language of “parents’ rights” now being deployed by Republicans and the larger white right is simply an updated version of much older white supremacist slogans and threats: the importance of “states’ rights,” the need for “local control,” the danger of “outside agitators” and the doctrine of “separate but equal.”

…

White right-wing evangelical churches and religious communities fervently resisted the civil rights movement — and today, they stand against the bogeyman of “critical race theory,” specifically, and the existence of multiracial democracy more generally.

And so on. To which my reaction is, well of course. Hasn’t everyone noticed? But these are precisely the things conservative parents *don’t* want their children to know about.

As it happens the article goes on to quote Umair Haque, the Eudaimonia guy I discussed in my post on Nov. 13th.

Haque:

So how did Youngkin win? He triggered White Rage. He sent white Virginians into a frenzy. They literally lost their minds — they stopped thinking. Nobody asked: “Wait, does this man have a plan, an agenda?” It didn’t matter. What did? Supremacy did.

…

[Yet] he did have an agenda, and he does have one. He told white Virginians the very same lies that Trump did. All those minorities and immigrants and foreigners are to blame for your woes. The soil belongs to you, because you are true of blood and pure of faith. Everyone else? Gay, immigrant, Jew, Black, Latino? They’re interlopers, aliens, who don’t belong here, and don’t deserve the same rights and powers you have.

This has been my perception of the Republican party for decades now. Their platform consists of 1) cutting taxes for the wealthy [because the wealthy are big donors to the Republican party]; 2) spending no-amount-is-too-much on the military [because the paranoids and war-mongers of society are Republicans); 3) prioritizing white Christian society, while denying they are doing so; and more recently 4) undoing everything the Democrats have done, even if it means harming their own voters. (Notice how in 2020 the Republican Convention had *no* platform, deferring, in effect, to whatever Trump wanted. Virtually the definition of a cult.)

\\

Some things never change, 2

Salon, 14 Nov 21: Cherry-picking the Bible and using verses out of context has been done for centuries, subtitled, “Theological arguments against the COVID-19 vaccines aren’t anything we haven’t seen before.”

(Reposted from The Conversation, 4 Oct 21.)

Again: well of course, hasn’t everyone noticed? Apparently not. The most obvious examples are people who find gays icky and so selectively cite Leviticus, for example, to condemn them, while ignoring all the other harsh prohibitions in that book that are today ignored.

In my own reading of the Bible — which is only partial — it’s obvious from the beginning that consistency is not its virtue. My private theory — I haven’t read enough biblical commentary to see if this is commonly understood, or if I’ve misunderstood along the way — is that the early editors of the Bible — the earlier parts during the Babylonian exile; the later parts in the 3rd century or so — left in lots of variant versions (two accounts of creation; gospels of Jesus that don’t agree with each other) because 1) they wanted to preserve any vaguely plausible ancient texts that they had around; 2) they knew commoners could not read the compiled Bible; and 3) they wanted pastors to be able to cite whatever Biblical passage suited their current needs. They *wanted* to be able to cherry-pick.

Ironically, once the Bible was translated into local tongues (despite the Church’s resistance) nobody seemed to notice or care about all those contradictions. And so still today, commoners and parishioners still cherry-pick the Bible to support whatever intuitive bias they want to defend.

The article, by the way, finds the situation a reason to regret Biblical access to ordinary people. Different interpretations of Biblical texts led to all those various Protestant denominations. And the writer concludes,

From my perspective, the response of some evangelicals to the vaccine reveals the dark side of the Protestant Reformation. When the Bible is placed in the hands of the people, void of any kind of authoritative religious community to guide them in their proper understanding of the text, the people can make it say anything they want it to say.

True enough, is my thought, but so can the “authoritative religious community” make it say anything they want it to say. The real lesson is that the Bible, a conglomeration of texts written over thousands of years (some after being passed down orally, for centuries), should be taken as a fascinating historical artifact, but as an authority on nothing.

\\

Some things do change, but people quickly forget.

The Atlantic, Joe Pinsker, 16 Nov 21: We Live By a Unit of Time That Doesn’t Make Sense, subtitled, “The seven-day week has survived for millennia, despite attempts to make it less chaotic.”

The New Yorker, Jill Lepore, 15 Nov 21: How the Week Organizes and Tyrannizes Our Lives, subtitled, “From work schedules to TV seasons to baseball games, the seven-day cycle has long ordered American society. Will we ever get rid of it?”

These are both in response to a new book by David M. Henkin, The Week: A History of the Unnatural Rhythms That Made Us Who We Are, just published yesterday.

Gist: while the 7-day week “has been deeply significant to Jews, Christians, and Muslims for centuries, people in many parts of the world happily made do without it, or any other cycles of a similar length, until roughly 150 years ago.”

Something like the 7-day week has existed since Roman times, but there was a shift in the 19th century. Henkin, quoted by Pinsker:

If you were to single out one factor, I would say urbanization. This really is a social phenomenon: It’s about people wanting to be able to make schedules with others, especially strangers, either in a consumer context or socially. When most people lived on farms or in small villages, they didn’t need to coordinate many activities with folks whom they didn’t see regularly.

This is like that piece about birthdays, discussed in my post on 10 November. Things change, things we take for granted in our daily lives, yet most people don’t realize such changes unless they occurred in their lifetimes.

Lepore’s essay isn’t an interview; it’s an exploration of the idea of the week, about the various versions and alternatives considered over the centuries.

The sun makes days, seasons, and years, and the moon makes months, but people invented weeks. What makes a Tuesday a Tuesday, and why does it come, so remorselessly, every seven days? A week is mostly made up. There have been five-day weeks and eight-day weeks and ten-day weeks.

…

There’s got to be a reason for seven, but people like to argue about what it could possibly be. On the one hand, it seems as though it must be an attempt to reconcile the cycles of the sun and the moon; each of the four phases of the moon (full, waxing, half, and waning) lasts about seven days, though not exactly seven days. On the other hand, the number seven comes up in Genesis: God rested on the seventh day. Another reason for seven lies in the heavens. Many civilizations seem to have counted and named days of the week for the sun and the moon and the five planets that they knew about, a practice that eventually migrated to Rome. Norse as well as Roman gods survive in the English names, too: Thursday, for Thor; Saturday, for Saturn.