Coincident to yesterday’s post is this essay today in Salon.

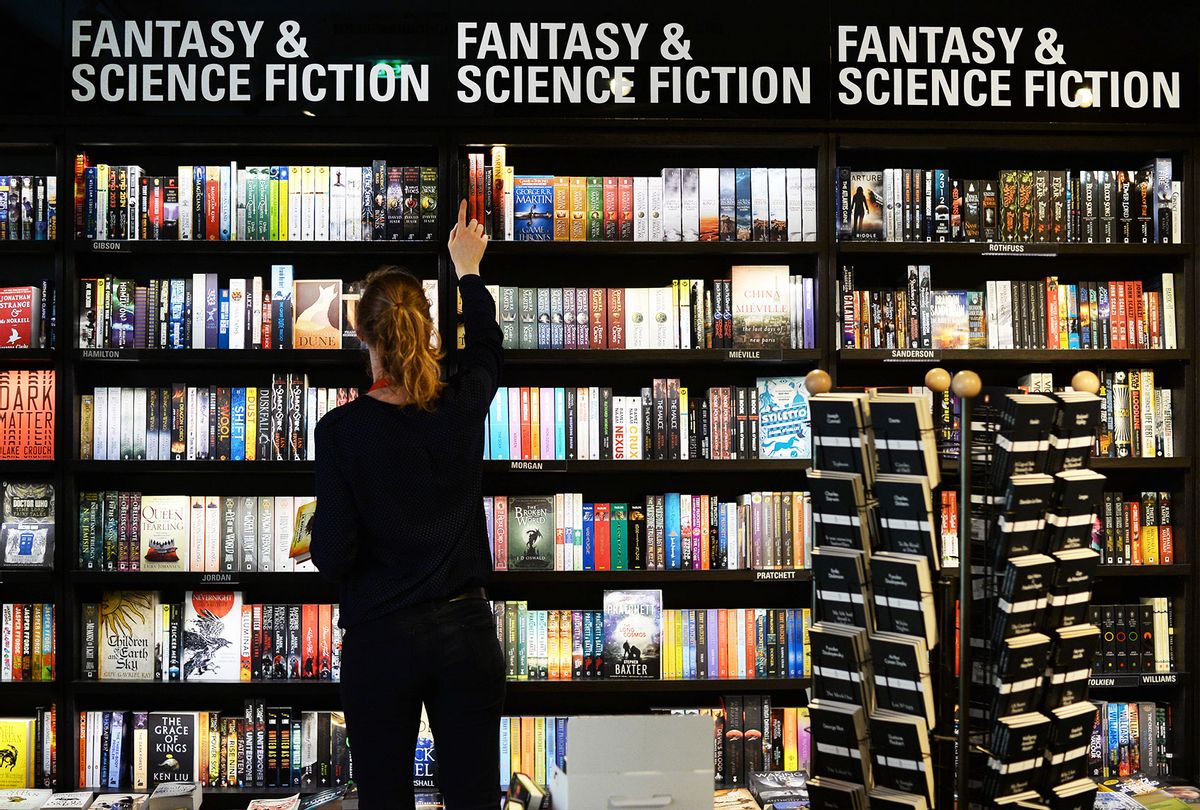

Salon, Kyle Galindez, 19 Feb 2022: Why can’t sci-fi and fantasy imagine alternatives to capitalism or feudalism?, subtitled, “The limitless imagination of genre novelists hits a roadblock when it comes to envisioning other political systems.”

I’ll quote the first paragraph, with his links (which are all to other posts on Salon, suggesting to me that some editor at Salon added them, not the writer).

Whether it’s through fire-breathing dragons, time travel, psychic powers, or spaceships that sail effortlessly between distant stars, there’s never been a shortage of tropes in fantasy or science fiction stories that challenge our belief of what’s possible. Yet while fantasy and science fiction authors are great at imagining new forms of magic and technology, authors aren’t so good at imagining different political systems. Indeed, for the most part, they fall back on the same old political or economic systems: for fantasy, we have our usual monarchies and empires, kings and queens, nobles and commoners. For sci-fi, the future is often bleak, dominated by hyper-capitalist corporate galactic warfare or techno-bureaucratic empires clinging to power on their newly-annexed planets.

The author has (self-)published a novel and is a PhD student at UC Santa Cruz.

I’m not particularly impressed by the essay. It spends an inordinate amoung of time on “Game of Thrones,” after that (despite his links) discussing Le Guin’s THE DISPOSSESSED, the TV show (not novels) “The Expanse,” the “Star Wars” franchise — and his own novel! And that’s it.

I saw this item first on Facebook, where commenters to the post point out many other ideas in SF — Robinson, Banks, Heinlein, and of course “Star Trek” — concluding that the writer simply isn’t very well read.

\

Star Trek, in its 1960s original TV show (TOS) and the 1980s Next Generation (TNG), is the most prominent counter-example to the writer’s thesis. (I haven’t paid close attention to the later iterations of the Trek franchise.) Trek explicitly imagined a world in which scarcity was a thing of the past and “money” was a very incidental issue. Yes, on the latter point, TOS mentioned “credits” and “salary” once in a while, but in TNG, as I recall, Picard made an explicit speech about how the 20th century concept of “money” simply doesn’t exist in the 23rd. (A Google search turns up several examples, actually.)

The economics of the future is somewhat different. You see, money doesn’t exist in the 24th century. The acquisition of wealth is no longer the driving force in our lives. We work to better ourselves and the rest of humanity.

How idealistic! And perhaps naive, given the selfishness and lack of concern for “the rest of humanity” we’ve seen in the last few years during the Covid crisis. The future in Trek somehow overcame humanity’s worst tendencies, apparently.

Still, the other primary evidence is Trek’s replicator, seen since early in TOS. If you can whip into existence anything by a mere command, then maybe money doesn’t mean much of anything; or to put it another way (now echoing Harari) if technology improves to the extent that productivity allows most people not to *have* to work at all, then capitalism will simply dissolve.

\

This brings me to a topic I don’t think I’ve discussed on this blog, yet, the idea of “retcon,” or retroactive continuity. This takes place typically when a TV episode, or movie based on a TV series (I’m thinking Trek of course), says something that contradicts and earlier episode or movie. Wikipedia’s example is how Arthur Conan Doyle explained away Sherlock Holmes’ apparent death in one story so that Doyle could continue writing (by popular demand) more Sherlock Holmes’ stories.

On a more modest level, Star Trek websites and Facebook groups are full of Trek fans (some very new and naive) wondering things like, “Why didn’t they use a shuttlecraft in ‘The Enemy Within’?” to take the first one that comes to mind. They keep asking questions that have been asked and answered dozens of times before, or that are readily available in books or on websites. It’s a compulsion. More evidence for humanity’s compulsion to understand everything as stories.

The true answer to virtually all of these queries is matter-of-fact: the episodes of any series, and the producers and writers of all the movies based on any series, are all different. They don’t have time to compare notes. Considering for a single TV episode how long script development, set design, and directorial planning takes before shooting, the week of shooting, and then the post-production special effects and music score composition and performance takes, sometimes many more weeks, it’s amazing that so many episodes get on the air, week after week. They’re done in parallel.

When “The Enemy Within” was written and produced, no one had thought of the idea of the Enterprise’s shuttles (or the writer, not having seen an aired episode of the show when he wrote his script, didn’t realize it), which we didn’t see until “The Galileo Seven” later in the 1st season.

(On the other hand…the Enterprise design itself, from the very beginning, had the shuttle landing bay built into the back of the ship. And Trek was unusual, if not unprecedented in its time, for having a series “Bible” written to inform writers for the series about the show’s basic premises. Still, the pace of a weekly TV series is hectic, and — here’s another point that is not widely recognized — in the 1960s TV episodes were produced to be seen once, or twice in a summer reruns, and then never again. So consistency was not the issue it has become in this era, of the past 30 years, of video and DVDs and streaming, where fans can watch shows over and over and spot all the inconsistencies the producers didn’t think about originally.)

Much more, perhaps an entire book, could be said about this.

Yet the idea of “retconning” is not new. It’s been happening for centuries, even millennia. It’s how writers of the New Testament kept trying to rationalize events from the Old Testament as fulfilling “prophecies” of events they recorded. Even if they strained, and mistranslated words, to try to make history and present-day consistent. These religious scholars are doing the same thing as Star Trek and Stars Wars fans, trying to rationalize disparate stories into a sensible whole, even though they’re just stories, not histories of actual events.

\\

Another note about Wordle. There is a “hard mode” setting, I’ve realized, so that when you play the game, any letters you’ve confirmed must be used in the same position as where you first found them. This makes the game, harder, of course, and less subject to clever deduction. I like the clever deduction, so I haven’t turned that option on.

As an illustration, the word on Thursday was “shake.” Many players — there are at least half a dozen of my Facebook friends who play it and post their results daily — identified “sha*e” relatively quickly, after three tries perhaps, and then spent their next few tries by plugging in plausible letters into the fourth spot. Shave? Shale? Shame? Shake? Shade? And they would run out of tries and lose. These players were using Wordle’s “hard” mode without realizing it (or perhaps they were, I don’t actually know). Even knowing about this, I prefer not to use the hard mode; it makes it into a game of chance, rather than of strategy. As I explained in previous post.

Today: swill, in four guesses.