Here’s the next part of the batch of brief reviews of SF novels that I began last week. I’m now thinking, though, that with more substantial books like this one I’ll just cover one book per post — back to my usual pattern of classic reviews here on this blog, if not like the detailed walkthroughs I did for a while, and for Black Gate. So here are my comments about Keyes; Clarke and Butler to come.

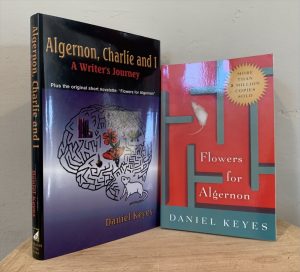

Daniel Keyes, FLOWERS FOR ALGERNON (1966) (edition shown here: Mariner Books, trade paperback, 2005)

This is a famous story, one of the most famous in science fiction. It was originally a novelette – a story some 30 or 35 pages long – published in a magazine in 1959, a novelette that won a Hugo Award. The author expanded it into a novel, published in 1966, that won a Nebula Award (in a tie).

The setup and story arc are memorable. Charlie Gordon, a 32-year-old “retarded” man with an IQ of 68, who works as a janitor in a bakery, is chosen to undergo an experimental brain treatment to triple his IQ. (The word “retarded” is used freely in the novel, though not at all in the earlier novelette.) The story is told in first-person via diary entries, initially in Charlie’s misspelled, ungrammatical prose:

progris riport 1 martch 3

Dr Strauss says I should rite down what I think and remember and every thing that happins to me from now on.

The treatment is successful but – spoiler – temporary, and is foreshadowed by the effects of the same treatment on a mouse named Algernon. The story arc becomes clear, early on, but is tragic and heartbreaking. This is not a book you want to finish reading in a room where you be embarrassed to be seen weeping.

The plot of the novel closely follows that of the original story, but expands in the center with some adult themes: Charlie’s attraction to a neighbor; his crush on his one of his doctors, and scenes in which he confronts the mother who didn’t know he was still alive. These passages have triggered attempts over the decades to ban the book, which is otherwise one of the most popular SF novels of all time.

The thematic take-aways are the ways in which intelligence affects our perception and understanding of the world. Of course. Before his treatment, Charlie is routinely superstitious, carrying a rabbit foot and a lucky penny; similarly, one of his nurses gets red in the face talking about Adam and Eve and God. As Charlie becomes more intelligent, he dismisses his superstitions, finds math and other languages intuitively obvious, studies widely and perceives flaws in the work of others, and even understands the basis for the rivalry between his two doctors that they themselves don’t realize. And then he loses it all, gradually, as he reverts.

So how far does this go?, is the question I derive from this story. If Charlie perceives things less intelligent people don’t, are there other things even more intelligent people might perceive that ordinarily intelligent people, or even Charlie, wouldn’t? And where is the balance of intelligence in human happiness? Charlie’s intelligence outstrips his emotional growth; he learns and understands more, but is no more happy.

Ultimately, I take this as an example of how human intelligence, and potentially the intelligence of other alien species, affects the understanding and control of the world. What would a truly superior alien intelligence find obvious that even the smartest humans can’t wrap their minds around? (Quantum mechanics, perhaps.)

\\

As I read this book I discovered that I had on my shelves a nonfiction book by Keyes, published in 1999, called Algernon, Charlie and I: A Writer’s Journey. So I read it through as well.

It’s a fairly typical writer’s memoir about the origins of his story, how he developed and changed versions of it over many years, and then what happened to it after publication, what with a TV version, a stage version, and ultimately a film version starring Cliff Robertson (called Charly).

But it’s unusual in that in this case we read about early entreaties from editors to change the ending to be a *happy* one — if only, e.g., a scene in which the mouse Algernon recovers, implying that Charlie will too. Keyes resisted, just as Tom Godwin did with “The Cold Equations,” and thus both stories are remembered to this day. Happy stories are ephemeral, perhaps; tragedies strike deep chords in us that last over time.

Another thing that struck me was how Keyes, who developed the story over many years, used people he’d met and incidents he’d witnessed as parts of his story. He wasn’t an intuitive writer, apparently, and had notions for the story years before he finished it, adding elements over time.

Other interesting bits:

- He describes encounters with Horace Gold (who wanted a happy ending), Philip Klass (who agreed no), Robert Mills, and especially Cliff Robertson, who declines the TV director’s instruction for a gesture to indicate a ‘happy’ ending, but who later contested a Broadway version of the novel.

- The Broadway version actually opened but quickly closed (after a negative review by Frank Rich of NYT). One of the songs, “Tomorrow,” was carried over by the composers to “Annie.”

- How the author learned not to “explain” what the story means, to fans. He describes a speech where he used letters from students who’d read the book. One asked if Charlie dies. Keyes answered, he doesn’t know.