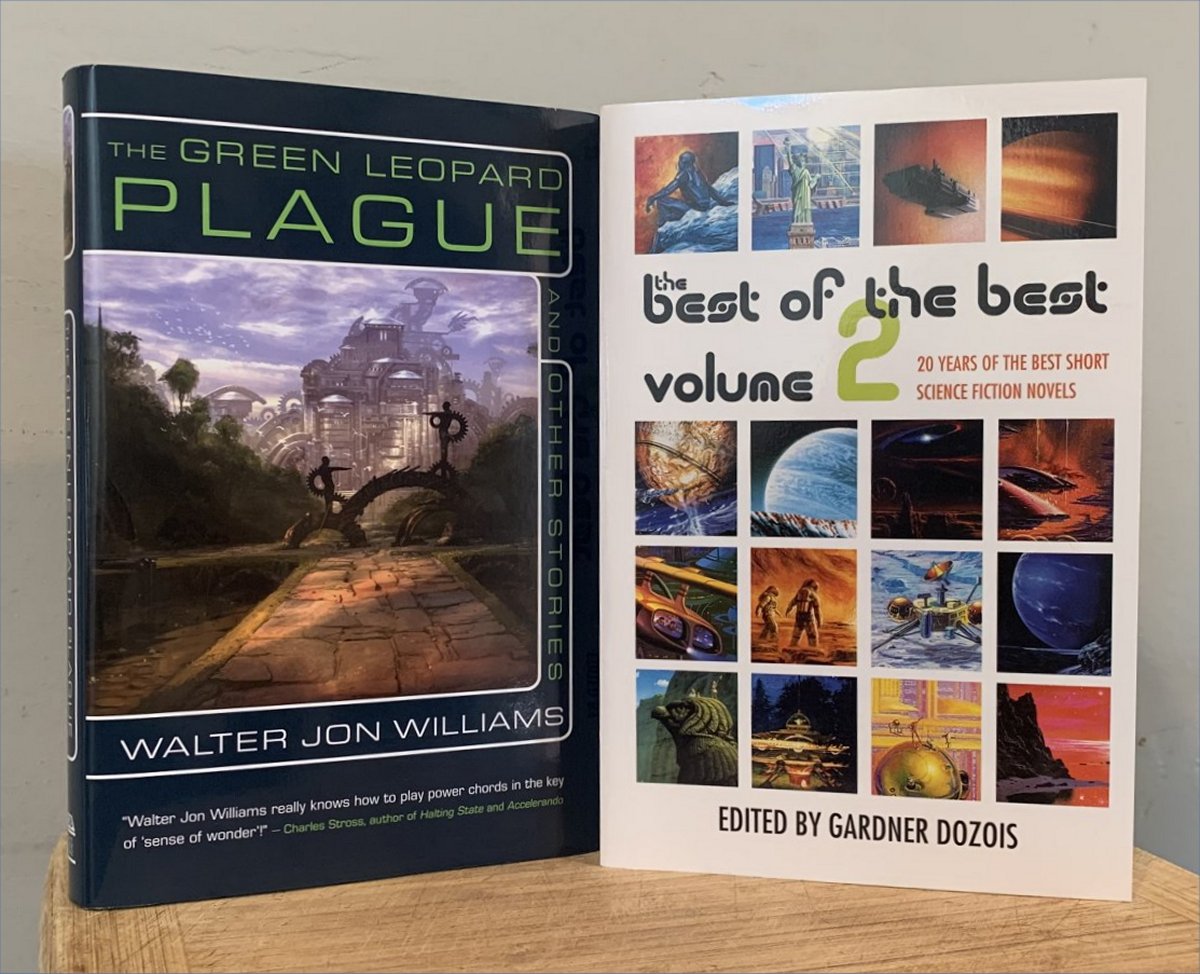

This week’s story being consider by the Facebook Best Science Fiction and Fantasy Short Fiction group, for its reading of the big Gardner Dozois book shown here, is the second story in that book, a 1988 novella by Walter Jon Williams called “Surfacing.” It’s about 60 pages in a typical book, fewer pages in this anthology with its tiny print. In this post I’m also reviewing two other notable stories by Williams, from 1999 and 2003.

Williams is a respected and honored writer who has perhaps never gained the following he might have, had he stuck to a particular genre or subgenre. Which is to say, almost no two of his books or stories are the same. He writes science fiction, and fantasy, and varieties of each. In one of the story afterwords in his book shown above, the author’s 2010 collection THE GREEN LEOPARD PLAGUE, he lists the kinds of stories he set out to write when he began his career, and the corresponding title of the book he did write on each theme. A future in which everything went right; another in which everyone went wrong; a mystery/thriller; a first-contact story; and so on. His earliest big hit, HARDWIRED, an early cyberpunk novel, was his take on the second theme. He finished everything on that early list; currently he’s writing a series of pirate novels beginning with QUILLIFER (since 2017).

The story at hand, “Surfacing,” is set on an alien planet where a human scientist, Anthony Maldalena, is studying deep-dwelling creatures in the planet’s oceans that he calls Dwellers. To assist him he has transported (through some handy-dandy unexplained device that also justifies humanity’s easy transport around the galaxy), a number of humpback whales. He can communicate with the whales, but is still working hard to decipher the signals he gets from the Dwellers. There are some neat diagrams at the beginning of the story (and again at the end) where he pairs literal and figuration interpretations of these signals, with some concepts missing.

Layers of plot ensue. It’s mentioned upfront that an alien Kyklops is visiting the planet, wearing a human body. A young woman, Philana Telander comes to meet Anthony, for help with her interest in learning how the language of the whale cows may have changed since being brought to this planet. Anthony is surly and uncomfortable, impatient with people, alcoholic and sometimes violent; we get some background of his childhood as member of a cult family who had isolated themselves on another world.

These layers converge. (Spoilers) Anthony despite himself, begins an affair with Philana; then learns that Philana is a puppet, of sorts, of the powerful alien Kyklops, whose name is Telamon; and Telamon confronts Anthony about his reticence in publishing what he’s learned about the Dwellers, and indeed even his reluctance to directly contact them. There is a series of dramatic scenes in which Telamon, occupying Philana’s body, taunts Anthony about the failures of his life. And it all builds to a moment when Anthony takes charge, determined to set things right – and summons the Dwellers from their deep.

This is a fine, dramatic, provocative story. And yet —

I mentioned earlier how the stories in this big Dozois anthology were originally published, more or less, across the span of years I reviewed for Locus Magazine. In fact, I reviewed this Williams story in the very first column I wrote, published in the April 1988 issue of Locus. In that column I covered the first four 1988-dated issues, January to April, of Asimov’s Science Fiction magazine, then edited (as it happened) by that same Gardner Dozois. (Charles Brown told me not to do that again – each column should cover the latest issues of a variety of magazines.) Dozois had begun the series of best-of-the-anthologies, of which the present volume is a selection, five years before; this Williams story was the lead in his Sixth Annual volume.

Here’s what I wrote then:

The April issue is very strong, and includes the best story from these four issues, Walter Jon Williams’ “Surfacing,” a long tale about a linguist struggling to decode the language of deep sea creatures on an alien world. The mysterious ambiguities of alien translation surround the more dramatic crisis involving a rich young woman from earth and another alien menacing both humans. This is a powerful story of personal conflict in an exotic setting.

(At least, this is what I wrote in the column I sent in. I know that Charles Brown edited my columns, especially near the beginning. He taught me never to say “It seems to me…” or “My impression is…” or similar phrases. Since my column was a by-lined review, i.e. opinion, column, I should state what I thought was true without any such waffle words. However, beyond the first such feedback, I confess I never read my columns once they were in print. So when I quote from them here, I am quoting the submitted manuscript versions, which might have been edited before publication. I do have the published reviews, of course, in the print issues of Locus I’ve kept all these years, but I’m not going to dig them out.)

Now… Upon rereading this, it strikes me as more of a drama among human and alien characters, a drama of passivity and control, and less a mystery about deep-sea dwellers. What struck me originally were those mysterious language diagrams, and how a human might possibly understand the language of creatures who lived so deep they had no experience of a world outside, or above. This notion has always fascinated me, similar to stories about aliens who live on planets permanently shrouded by clouds. What kind of cosmos would they envision? What kind of cosmos *could* they imagine? And is it possible we humans suffer similar limitations in our perception of the universe that we cannot be aware of? (Yes, if only because we do not see UV or infrared or much else of the EM spectrum beyond a narrow range.)

So on this reading, I’m disappointed that Williams gradually revealed that, well, the Dwellers do know about the surface, even somehow knowing about this planet’s sun. And at the end – again, spoiler – all it took was for Anthony to finally send them a message for a Dweller to rise and, despite the difference in pressure from their deep, come to the surface, fully alive. It’s a dramatic finale, a represents a psychological story arc for Anthony, but it diminishes the potential mystery of such potentially remote aliens.

\\

I decided to read a couple of other WJW stories this week, perhaps as a beginning of a weekly trend. (One story in the anthology the group is reading, plus my own revisitations of a couple other classics stories by the same author, perhaps.)

In this case there were two stories by Williams that were both Nebula Winners and which, as best as I can remember, I *never* read until now. The stories were “Daddy’s World,” published in 1999, and “The Green Leopard Plague,” published in 2003.

It’s easy to explain why I hadn’t read the latter story. When I gave up (partly involuntarily) my Locus column at the end of 2001, I went virtually cold turkey from reading short fiction, or much of any science fiction, for several years. I didn’t even read the works that won the Hugo and Nebula awards, for several years. (To this day my familiarity with 21st century short fiction is very limited. A bit in the way people have music from their teens and twenties memorized, but couldn’t identify current pop stars, though my reasons were different.) The earlier story, on the other hand, was published during a year I was still reviewing for Locus, but in an unusual venue, a paperback anthology that I didn’t get to, though I was still covering the regular magazines that year.

“Daddy’s World” is about a boy, Jamie, who with his family (parents and sister) visit various magical peoples and places: the Whirlikins, tall people with pointy years; a castle he’s not allowed into until he learns his Spanish irregular verbs; Selena, who rides a beam of light from the moon to sit by him at night. This kind of situation is common in science fiction and fantasy, beginning in media res without explanation, and part of the fun of reading such stories is trying to figure out *what’s going on?* from the author’s indirect clues before the situation is finally spelled out. Here the boy Jamie is obviously in some kind of world that he is either imagining, or that has been created for him. Clues are the cracks that appear: one night his family all freeze in place, and he hears a voice talk about “interface crash”; later he realizes his sister Becky is growing older faster than he is; and then Becky, or whoever is playing her, breaks down and explains most of what Jamie needs to know.

(Spoilers) Recalling a bit Pat Murphy’s “Rachel in Love,” this story is about a child who has died and been ‘resurrected’ in some sense, in this case as a holographical model of his original brain inside a virtual environment. (In Murphy’s case a daughter was downloaded into a chimp.) Jamie is in a program; he *is* a program, until a clone of his original self can be built. But it’s an expensive project and may not complete.

Here’s another story, like Silverberg’s “Sailing to Byzantium,” in which the main character’s realization of who he really is has profound philosophical repercussions. Jamie becomes angry and bitter. He realizes he can play with his environment — he can do anything. If so, what does anything mean? When he interfaces with his real mother, he guards against feeling sorry for her — it’s just electrons moving, he thinks. Time passes, his world shrinks, his parents die, and Becky is in charge. What does he want, she asks? To be erased.

That’s not the very end. The story speculates on the implications of this technology (as all good science fiction should). If virtual worlds creating any reality can be built, what’s to stop people from raising their children inside environments designed to conform to their religions, with churches, angels, and the presence of God? Or even something as relatively benign as Jamie’s father’s yearning for a “normal family life”… forever?

\\

“The Green Leopard Plague,” first published in 2003, is a novella, about 60 pages in the book of the same title shown above. Like “Surfacing,” it’s a multilayered story of overlapping plots. But the plots, and themes, are more cohesively science fictional than in “Surfacing,” and so I rather like this story better.

The frame story concerns a woman, or mermaid, Michelle, who lives alone on a small Rock Island in the Philippine Sea. She was once an ape; a human before that. Her age is one in which when people die they can easily be resurrected via backup copies (as in John Varley’s stories of the 1970s), yet she once suffered the apparent “realdeath” of her partner Darton, who nevertheless has reappeared and is trying to find her.

She is good at computer research, using “research spiders” (a term also used in “Daddy’s World”), and is contacted by a client to find out what happened with a famous man, Jonathan Terzian, who just before he came up with his revolutionary “Cornucopia Theory” disappeared for three weeks. She accepts the job and uses her spiders to find images of him of the places he appeared during those weeks, and put together his story.

This foreground story alternates with the background story of Jonathan Terzian, an interdisciplinary academic who, while in Paris, witnesses a man being killed on the street by several assassins. He is contacted by a woman, Stephanie, who claims she is an associate of the dead man, a biochemist who was smuggling out, from a former Soviet “Trashcanistan” (cute term) called Transnistria, a copyright for a biochemical invention that could revolutionize the world: a way to implant chlorophyll into primates like humans, enabling them to gain energy from the sun. It would solve world hunger, and remove the weaponization of starvation. But the Transnistrians are after her, to stop her.

The story alternates the two plots: Michelle putting together the clues, Terzian trying to bring this biochemical discovery to the world. This backstory we come to understand was the beginning of the transgenetic revolution that led to Michelle’s reality — even unto the reappearance of her supposedly dead partner Darton.

The emotional core of the story is Michelle’s relationship with Darton. At the end (spoiler !!!) she encounters and kills him again; not so big a deal, apparently, in a world when people can easily be resurrected. (I frown a bit at this; I recall Varley took this more seriously, since people were never happy waking up having lost months or years of their lives.) The intellectual core of the story is the author’s speculations on what this invention would mean. When food is free, what happens to the economy? What would the motivation be for anyone to do dirty jobs, like repair railroad tracks or clean the sewers? In earlier centuries despots would simply order citizens to do such jobs: making them slaves. So, slavery or anarchy? Or does it boil down to labor as the basic currency? I love stories like this that speculate on big issues, how the world might utterly change, even based on a single seemingly uncontroversial improvement in technology to make life better for all. There are always unforeseen consequences.

\

The author’s note in the book GREEN LEOPARD PLAGUE refers to an earlier story with the same idea, which he says is Fred Pohl’s 1965 story “The Anything Box.” Say what? That was the title of a 1956 Zenna Henderson story (which I don’t think I’ve read), but not a Pohl story.