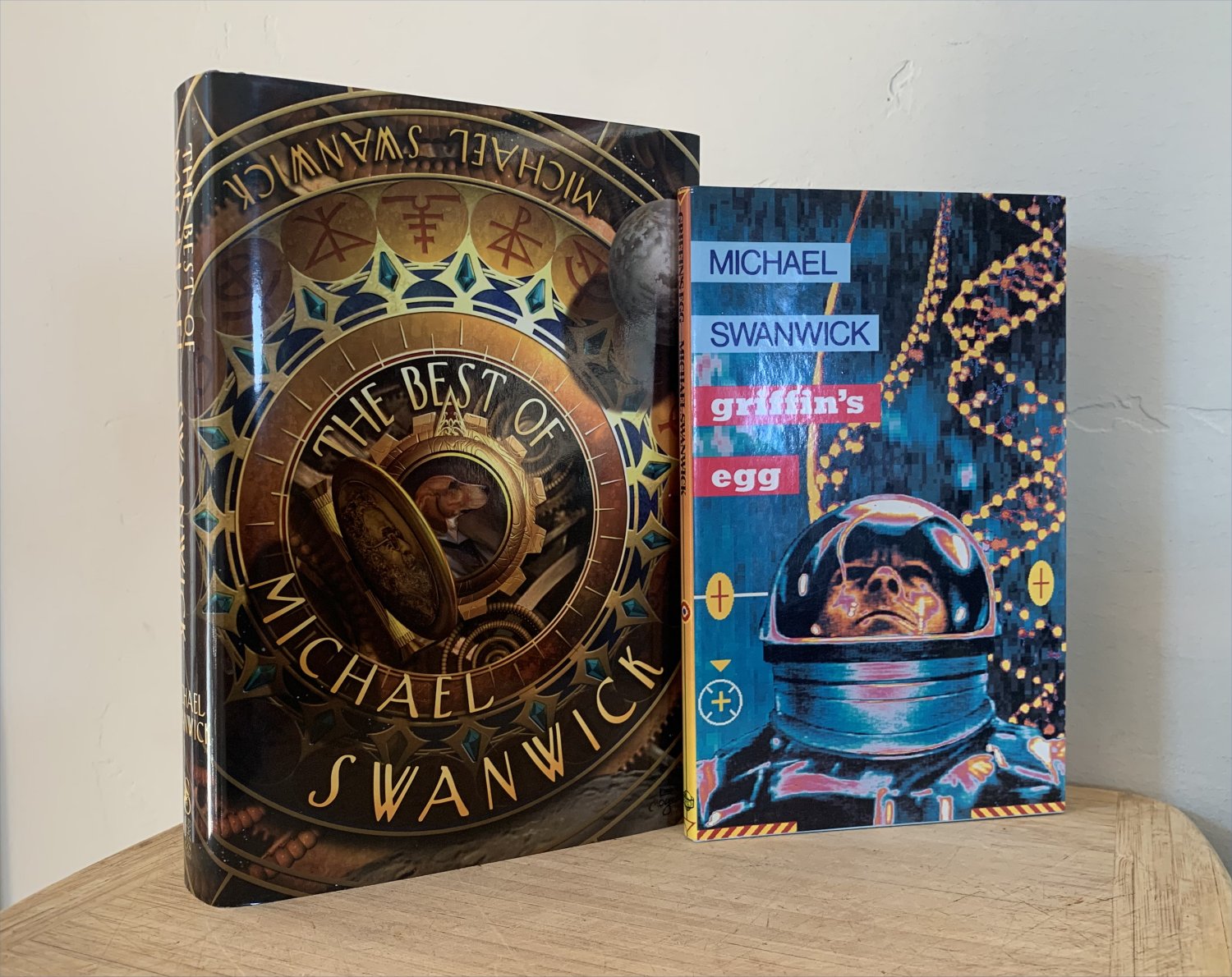

This week’s novella covered by the Facebook Group reading Gardner Dozois’s big anthology first discussed here is “Griffin’s Egg” by Michael Swanwick. It was first published as a “chapbook,” a smallish, thin book in a UK publisher’s series of such books, in 1991, and was reprinted in Asimov’s SF magazine’s May 1992 issue. Among other places, it’s also included in The Best of Michael Swanwick from 2008; the other four stories reviewed below are in this book as well.

Swanwick had been around a decade or so by 1991. He debuted with two stories in 1980 that, remarkably, were *both* nominated for a Nebula Award. Stories and novels followed at a steady pace, with “The Edge of the World” winning a Sturgeon Award in 1990 and Stations of the Tide winning a Nebula in 1992. And even more remarkably, five Hugo Awards in six years for as many short stories and novelettes. (See http://www.sfadb.com/Michael_Swanwick)

“Griffin’s Egg” is set on the Moon some decades hence, and nearly the first half concerns a worker named Gunther Weil as he tours mining operations, hangs out with friends, gets into some minor work trouble, survives a solar flare radiation spike while out on the surface, and wonders about one of his friend’s secret scientific projects. He’s subject to an officious inspector from Earth, Ekaterina Izmailova, with whom he promptly falls in love.

Then radio turns to static and on the Earth in the lunar sky they see a pinprick of light. Then another. War has broken out on Earth.

This is of concern to those on the Moon because they can’t survive without regular supply runs from Earth and from the Swiss Orbitals.

Then their base, Bootstrap, suffers an attack, some kind of biological weapon that leaves the majority of residents deranged and barely functional. Those unaffected try to impose some order, repair damage, and maybe — cue that secret scientific project — even find a cure.

The story is a technological thriller with a deep underlying scientific theme–what is human nature? Abstractly, this comes up early on as one of Gunther’s friends mocks his passive/aggressive behavior, accusing him of being merely a robot, acting out standard issue primate behavior. Later we see how those afflicted by the bioweapon, dubbed “flicks,” are treated as inhuman, with lessons about the Prisoners and Guards experiment, and Hannah Arendt. How hyperactive brains are given to conspiracy theories. How these primate behaviors are now existential threats. What to do? Can the brain be rewired? Should it? Would that make people inhuman, or would it be like the near-sighted getting glasses?

Credit to the author and story that the story doesn’t insist on any particular answer. Arguments can be made both ways. Some practice doing such “rewrites” will be needed. The story, somewhat like Joe Haldeman’s “None So Blind,” sets the stage for a potentially (r)evolutionary change in the human condition.

\

I was likely even more impressed by this story when I first read it in 1991 (I bought the Legend chapbook edition at the Worldcon that year — in Chicago!). Ideas about human nature, the reptile brain vs higher functions and so on, were fairly new then. (E.O. Wilson’s 1980 On Human Nature was still controversial.) In the intervening years such ideas have become orthodox, if still disputed by non-scientific ideologues of all political persuasions. Books by Daniel Kahneman, Jonathan Haidt, Steven Pinker, David McRaney, Yuval Noah Harari, and of course E.O. Wilson have explicated these ideas and made them commonplace. Swanwick, on page 67 of the chapbook, has a character ask, “Do you realize that we are trying to run a technological civilization with a brain that was evolved in the neolithic?”

E.O. Wilson, in one of his later books, said something almost identical… which as soon as I track it down, I will insert here.

\\

I reread several other Swanwick stories this past week.

“The Very Pulse of the Machine” (one of those Hugo winners) from 1998 is about an astronaut stranded on Jupiter’s moon Io after her ship flips over in a blizzard and kills her partner, Burton. Now she drags Burton’s body back toward their lander, her only chance of survival. And then Burton speaks to her — or rather, something is speaking to her, through Burton’s body. The very planet, it claims, trying to explain about triboelectric sulfur and orthorhombic crystals, and quoting passages of poetry from Burton’s brain to express what it can’t easily express in an unknown language. As in “Griffin’s Egg” here is Swanwick doing hard science fiction, though again with an ambiguous conclusion. Is this real, or is she hallucinating from the stimulates she keeps taking to keep going? It offers her a chance for immortality. She makes a decision. Swanwick makes you believe that, either way, she is reaching a state of transcendence.

“The Dead,” from 1996, didn’t win a Hugo but it’s the shorter Swanwick story that Dozois chose for his first Best of the Best anthology. It’s set in a near future in which technology has allowed the reanimation of corpses for service labor. And other things. The story follows corporate whiz Donald being recruited by old flame Courtney to a company that’s made a breakthrough that will make the “zombies” cheap enough for factory labor. They dine in a fancy restaurant attended by zombie busboys, and witness a savage fisticuffs fight between a man and a zombie. Then Donald discovers that Courtney enjoys another kind of zombie service.

The power of the story is the creepiness of the zombies, of course: the lifeless white skin of the busboys; and implacable power of the fighter; the attraction, for some, of their eroticism. Setting aside the implausibility of reanimating zombies for now, the deeper theme is existential. Will the mass of living people react to never holding a job again? Or maybe they won’t care. Either way is a frightening prospect.

“The Edge of the World” from 1989 isn’t science fiction, it’s fantasy of a sort, mixing realism and mythopoeia as three teenagers, against a backdrop of escalating global threats, leave their American military base to pass through the native quarter to reach the Edge of the World, the top of a cliff with steps that lead infinitely downward. They climb down, reflecting on historical events from Napoleon’s 1810 volley into the nothingness and Neil Armstrong’s planting a flag on the moon. Eventually they find caves, and one of the boys relates, or imagines, the Sufis who once lived there, and how they prayed a king into nonexistence. Nonsense, says the girl; there’s no such thing as magic. But what is magic, in such a place? Yet again, Swanwick offers an enigmatic resolution. (This Fantasy Magazine interview from 2011 explains some of the inspirations for and fantastic references in the story.)

Finally for now, “Scherzo with Dinosaur” from 1999 (another Hugo winner) is about time travel to the past, specifically to show tourists dinosaurs. As a glitzy benefit, the Cretaceous Ball, begins, narrator Don is on the looking for any funny business, from disputes between guests to staff attempts to violate paradox rules. Don takes a shining to one of the guests, a young boy besotted with the dinosaurs through the windows; the boy reminds Don of himself at that age. Sure enough, a series of incidents ensues that involves genuine paradoxes and revealed hidden identities in the best Heinleinian manner. Also–as in all the other stories reviewed here–Swanwick identifies an issue more fundamental than the problem at hand, and suggests two ways out of it. Here you can guess what Don will likely do, but as always Swanwick is canny in writing stories that are really about big issues with no easy solutions.