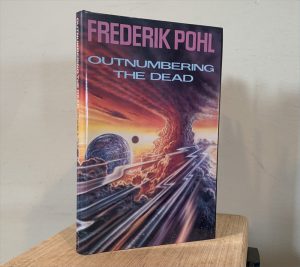

This week’s novella covered by the Facebook Group reading Gardner Dozois’s big anthology first discussed here is “Outnumbering the Dead” by Frederik Pohl. Coincidentally, it was first published as a chapbook, in December 1992, in the same UK publisher’s line as last week’s story, Michael Swanwick’s “Griffin’s Egg.” Both were later published in Asimov’s Science Fiction, Pohl’s story in the November 1992 issue.

Pohl’s long career included many roles: editor, writer, agent, fan. He edited magazines in the 1940s; in the 1950s he edited one of the first series of original anthologies, Star Science Fiction. He wrote fiction in the ’50s, notably with coauthor C.M. Kornbluth, including the advertising-industry satire The Space Merchants. After a lapse he returned to writing in the 1960s (with stories like “Day Million”) and then in a major way in the 1970s, producing one of the most popular SF novels of all time, Gateway (1977) and a string of others.

The decade from the mid-1970s to the mid-1980s was likely his peak. In that period he also wrote short fiction including “The Merchants of Venus” (a prequel to Gateway) and “The Gold at the Starbow’s End,” two novellas I suspect are his most popular. Later novellas (aside from those incorporated into novellas) were this one, “Outnumbering the Dead,” and “Stopping at Slowyear” (1992, another chapbook).

\

The scenario of “Outnumbering the Dead” is a familiar one. Some hundreds of years in the future, genetic treatments have allowed most human beings to become effectively immortal. Since people haven’t stopped having children, the world population has boomed–up to some ten trillion. More people alive than all the people who once lived and are now dead.

People live in huge arcologies, like the one in Indiana where our protagonist, Rafiel, lives. He’s a vid star so famous he needs only one name. But he’s infamous for another reason: he’s a “short-timer,” one of the rare people for whom the in vitro treatment for immortality did not take. He has another 30 or 40 years to live, at most, and he’s bitter about it. What’s the point of living, he wonders, if you know that it will end?

Two or three plot lines parallel for a while then merge. In the foreground, Rafiel is to star in a new musical film of Oedipus. He meets the composer, the dramaturge, the other stars, and rehearsals ensue. In passing the details of this production are hilarious: it’s a musical with *tap dancing* and lyrics like “I’ve killed my pop and shtupped by dear old mom.” / “It’s okay, dad, we’re all with you.”

In the background Rafiel is contacted by an old flame, Alegretta, who sends him the gift of a kitten, a gesture of later significance. And another dramaturge contacts him about starring in a play about Hakluyt, a ship about to leave for Tau Ceti.

Then Rafiel falls ill, barely finishes the on-location production of Oedipus, then deals with the two other issues, which become the same issue.

This is a fine story with a lot of interesting, if familiar, ideas. Pohl is thoughtful about the implications of long lives, especially how they open up so many options, e.g., plenty of time to start over and take on an entirely new professional career. At the same time perhaps society has stagnated; why send a starship to Tau Ceti? “What else is there to do?” Alegretta replies.

Still, I don’t understand the story’s preoccupation with Oedipus. Is there some thematic parallel I’m not seeing? Or is it just an example of this era’s peculiar artistic tastes, while they would no doubt see ours as equally peculiar?

Two little bells rung as I reread this story that reminded me, of all things, of Robert A. Heinlein’s Beyond This Horizon (1942 Astounding serial, 1948 book). This first was the basic question: what is the point of living? The second was the specific mention of dining in a multi-tiered restaurant where nets are installed to catch anything dropped from one of the balconies. Heinlein has an incident in his first chapter in which someone drops a crab leg over a balcony (without such a net) and hits another diner (leading to a shoot-out with Colt .45s).

Further, Heinlein and Pohl’s answers to the big question are different, but in practice are subsumed by the same thing. Heinlein’s answer was that life was meaningless without an afterlife, and sought evidence from telepathy and past memories that afterlives exist. Pohl’s answer, a little vaguely to avoid being spoilerish, is to accept death if it occurs but to be part of the greater cycle of life. In practice, those concerns become academic in the face of actually maintaining that cycle of life. The questions and answers are meaningless if there is no next generation.