Here’s a recent nonfiction book with a provocative thesis and some interesting points which nevertheless I give a mixed review of.

Here’s a recent nonfiction book with a provocative thesis and some interesting points which nevertheless I give a mixed review of.

Perhaps helpful to consider scoring the book along several independent parameters, like on some of those cooking shows, e.g. Iron Chef.

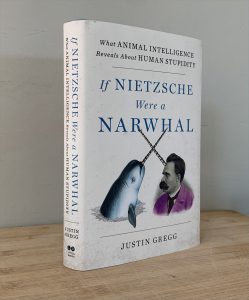

The author is an adjunct professor at a university in Nova Scotia. This seems to be his first book.

For book design and presentation, it scores, say, a 2 on a scale of 1 to 5, 5 being best. Because it has inordinately large type. It’s 300 pages, and so looks like a substantial book, but with a more typical font size, it would be 250 pages or fewer, I suspect. It gives the impression that it’s written for teenagers, or that the publishers thinks it’s an insubstantial book that needs a bit of puffing up to look like a real, adult book.

For thesis, it gets a 4. Let’s stipulate where we are (in this blog’s ongoing discussion) in fitting this book into some kind of context. The subtitle is “What Animal Intelligence Reveals About Human Stupidity,” and reviewers (the book was summarized in an issue of The Week a while back – book of the week, in effect, rather an honor) crowed over the idea that humans are really stupid (compared to the intuitive animals, perhaps), or that our intelligence is in some way counterproductive.

Before reading the book I wrote, Going in: we’ve established that most people don’t know anything about the universe outside their immediate community; further, that they don’t need to; even further, it’s probably just as well. (See Provisional Conclusions numbers 12 and 13.) So is this book an expansion of that third idea? That possessing knowledge, perhaps, derails our instinctive/gut sensibilities for how to live, and thus such “intelligence” amounts to a certain sort of stupidity? We’ll see.

Conclusion after reading: The subtitle oversells the book, to the point of hyperbole. It’s not about how humans are “stupid.” It’s about humans are, at times, too smart for their own good; our intelligence gets us into trouble at times, perhaps even threatening our survival as a species. Other animals don’t do this. (For animal “intelligence” and “perception,” I suspect Ed Yong’s recent AN IMMENSE WORLD is far superior to this book.)

Narrative: score of 3 out of 5. A lot of this information is familiar, but Gregg writes as if you’ve never heard of it before, belaboring even simple principles. Entire chapters go by without establishing much of anything.

Bits here and there: 4 out of 5. Despite which, here and there are some good insights, a new term or two.

Now I’ll step through the book and capture key issues, along the above lines.

- Intro. As the title indicates, the author uses the life and ideas of Friedrich Nietzsche (hereafter FN) to counterpoint how animals, e.g. narwhal (chosen for no particular reason other than the author finds them charming) live in the world. Author discusses the difficulty of defining “intelligence,” and offers an interesting anecdote about how FN’s German nationalist sister, Elisabeth, “retconned” his work to fit white-supremacist ideology. She perverted his reputation, in an example of using intelligence to justify savagery.

- Ch 1 The Why Specialists. How humans have forever asked “why” about how the world works, to the point of developing superstitions, folk medicine, etc., that vanish upon close examination (i.e. science). Why did humans begin doing this only some 40,000 years ago? Humans have accumulated a lot of “dead facts” that are useless in plain survival. Animals don’t bother with these; they ‘get the job done’ (i.e. surviving) by instinct.

- Ch 2 To Be Honest. All about the human propensity to lie, to the point of fooling oneself. The problems of truthiness, propaganda, and being able to detect these. Good in the short term, for individuals; deadly in the long term, for the race.

- Ch 3 Death Wisdom. Humans, unlike virtually all animals, understand the inevitability of death. On the one hand, this compels humans to create monuments that will last forever; on the other, consequences are depression, anxiety, suicide.

- Ch 4 The Gay Albatross Around Our Necks. Examples, e.g. of the French visiting Japan in 1868, of how differing moral standards led to mass suicide. The human sense of ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ change as societies evolve. As early humans began hunting in pairs, the need to understand one another led to ‘collective intentionality’ and then ideas of ‘us’ vs. ‘them’. Then ideas that morals must come from supernatural entities. Examples of how human ‘morality’ has justified genocide—the Church. Of all animals excepting chimpanzees, humans excel in killing everyone in rival groups. They create ‘morality’ around things like homosexuality, which is actually entire ‘natural’ and doesn’t cause any ‘problem.’ The history of our species is the story of moral justification of acts resulting in pain, suffering, and death. Human morality might be a bug, not a feature.

My comments so far:

- Solution to the Fermi Paradox? Smart creatures kill themselves off.

- This book risks being fodder for conservatives who think that ‘eggheads’ are more trouble than they’re worth. (Coastal elites, and most teachers, in current conservative political parlance.) This has happened in the past, e.g. Cambodia’s “Killing Fields,” and is the scenario for many a science fictional dystopia in which religion has taken over the intellectuals are banished or killed.

- By chapter 4, I’m thinking the conclusion here is that the bad things in human nature are consequences of the same cognitive skills that give us the good things – the ability to organize in large groups, the curiosity to explore the world, and the ability to build a global, technological civilization. Can’t have one without the other.

- So the solution to the problem, especially those of toxic morality, is to *think around* the moral ‘reasoning’ we inherit.

Pause for now; will finish tomorrow. (And likely revise the above.)