With an endpiece about stars.

Here’s an intriguing article, fairly long, that examines how the humor of liberals and conservatives differ. Since its core conclusions are consistent with so many other observations about the differences between liberals and conservatives — admittedly two crude endpoints, or constellations of traits, in a multidimensional spectrum — they sound plausible. I think the article is on to something.

(It’s long been observed that conservatives don’t do comedy. At least not well. They’re too angry and afraid to be funny. Just try to think of a time Trump was in any way humorous, except when making mean-spirited put-downs of his political enemies, using juvenile nicknames, or of anyone whom he thinks has betrayed him (there have been so many!), that his fans, at least, find funny.)

Vox, Constance Grady, 20 Dec 2022: Is the right winning the comedy wars?, subtitled “Why liberals and conservatives don’t get each others’ jokes.”

It begins by discusses a new show on Fox News called Gutfeld!, which is doing very well in the ratings. Samples of his shtick, and the patter by his recurring personalities, are familiar put-downs of Democrats and other (more left-wing) late-night show hosts. The article writer finds this a change from the verities of a decade ago, when late-night shows tended liberal and conservatives were considered humorless. Despite “critics apparently bewildered by how anyone could possibly laugh at this show.” This specific show aside, Grady writes,

It’s as though there’s some sort of fundamental disconnect between right and left on the issue of comedy. On a very basic level, the two sides seem to disagree on the question of what a joke should look like, what it’s okay to joke about, and what is so under threat that to joke about it would be unthinkable.

The writers speaks to several “humor theorists” about how the right-left divide involves different versions of reality, and therefore humor.

According to Young, liberals like jokes based in irony and misdirection that end in a surprise punchline, while conservatives like jokes based on exaggeration and grotesqueries that say what they mean from the beginning and then escalate.

“The general structure of a political [liberal] late-night joke tends to use incongruity,” says Young. “You as the audience are asked to make a series of incongruous ideas fit together.” Doing the work to make those two parts fit together is what makes the joke funny.

[…]

In contrast, Young argues that conservative humor, including Gutfeld’s, is often built on the model of a “yo mama” joke: You state a premise once, and then you keep repeating it in increasingly absurd ways.

And why would there be this kind of difference? The article digs deeper.

Young’s theory is that liberals like satire because they’re less concerned with danger than conservatives are. “Liberals are less attuned to threat in their environment. They’re not as stressed about whether or not they’re going to be the victim of crime,” she says. “This translates to a higher need for cognition. They are less worried about someone coming out of the shadows, which gives you the luxury of being able to sit around and think.” Liberals, in other words, have enough time on their hands to like jokes that make them work a little bit, in the same way they might like cultural products that make them work, like jazz or abstract art.

In contrast, Young argues that conservatives are constantly monitoring the world for threats, and as a result, they’re less patient with ambiguities and uncertainty. “Conservatives like things that are more fully cooked: art that looks like what it’s supposed to look like, songs with a straightforward breakdown, and straightforward jokes,” she says.

Young’s theory, to be sure, has a certain resonance with such classic culture war fights as “My Kid Could Draw That” and “Who Actually Likes Opera?”

Others disagree.

Young’s critics, however, argue that her framework is just more liberal posturing, and that all she’s really saying is that conservatives are too stupid and unsophisticated to understand satire. Still, “this is not about sophistication or intelligence or political knowledge,” Young says. “Our survey research shows conservatives are high in political knowledge. You could just as well say liberals waste a lot of valuable time chewing their cud. They cannot make a decision to save their life.”

My comment: this echos yet again the idea that conservatives think in terms of black and white, and accuse liberals, who see in shades of gray (or even color) of being “unable to make a decision.” (Ann Coulter railed on this point years ago.)

Then there’s the sense, the article goes on, on the right that the left has become increasingly prim. (“That’s not funny!”) For criticizing their hate speech.

And so on. Closing lines:

Perhaps most importantly: If what you think is funny defines and is defined by the version of reality in which you live, then the person who most people think is funny is the person whose sense of reality most people are currently sharing.

So right now, it’s Greg Gutfeld’s world. We just live there.

\\\

Again, the cited characterization of conservatives as more concerned about threats than liberals, and more given to things that are “fully cooked” i.e. unambiguous and lacking nuance, matches the working theses I’ve made about the range of human nature, based on Jonathan Haidt’s “moral foundations” theory and others building on that.

They also match underlying premises in Michael Shermer’s 2015 book The Moral Arc, which this month I am finally getting around to reading in full. (Guess who are the good guys and who are the bad guys in the history of moral progress?)

\\

Endpiece

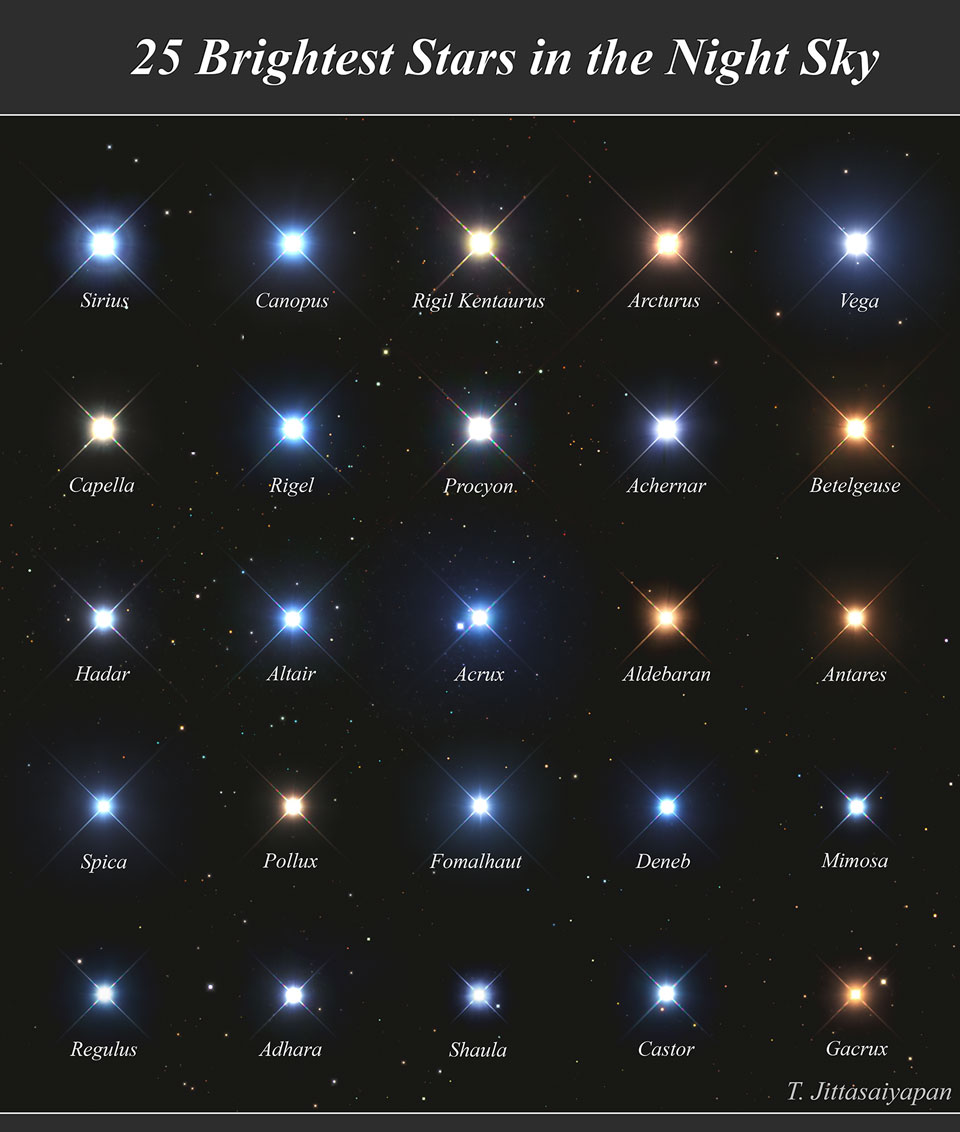

Here’s a handy-dandy chart of the 25 brightest stars in the sky, in order, courtesy APOD.

I have not done any serious star-gazing in years, even decades, and I miss it.