Today’s three topics: A conservative’s take on a fantasy novel; A Le Guin fantasy novel; And insights into books by Heinlein and Brockman.

Slate, Laura Miller, 6 Jan 2023: The Tolkien of the Times?, “Ross Douthat posted the first chapter of his epic fantasy novel, asking, ‘What should I do with it?’ Slate’s book critic has some notes.”

Two items by or about Ross Douthat in two days! I’m short on recent items so I scrolled down and found this one from about a month ago. The conservative columnist for the NY Times has apparently written a fantasy novel and can’t sell it. He posted a portion of it for free, inviting feedback. Laura Miller, crack book critic for Slate, took him up on the invitation. She begins:

New York Times opinion columnist Ross Douthat recently revealed that he has written the first volume in a trilogy of fantasy novels. Titled The Falcon’s Children, it has not been a hit with the “reasonable list of reputable publishing houses” Douthat says he’s submitted it to. In an end-of-year what-the-hell mood, the author posted the prologue and first chapter to his otherwise dormant Substack. “Why,” New York magazine’s Choire Sicha asked on Twitter, “are publishers not desperate for Ross Douthat’s fantasy novel? History tells us this the one thing you actually do want a tortured moralizing Christian to write!” In keeping with Douthat’s good-faith request for feedback, here’s a good-faith critique that might help answer Sicha’s question.

Before reading Miller’s critique, my first reaction is, why a trilogy? He all fantasy writers write trilogies and he wants to be just like them? And for that matter, why fantasy? Miller goes on,

The point about tortured moralizing Christians and epic fantasy is well taken, since the high-fantasy genre was founded by just such a person, J.R.R. Tolkien. Like Douthat, Tolkien was a Roman Catholic, which put him at odds with the predominant Anglicanism around him at Oxford, much as Douthat’s Catholicism stands out at the largely secular Times. While the church doesn’t oblige its members to subscribe to Tolkien-style essentialist understandings of good and evil (Tolkien’s elves are essentially good while his orcs are essentially evil), it certainly encourages that outlook. Clear-cut moral conflicts are one of the pleasures traditional fantasy offers its readers.

Miller admires the prologue, reminiscent of Neil Gaiman and Susanna Clarke she says. But then Douthat goes wrong by switching the focus to a “naïve central character” and then focusing on massive amounts of backstory.

…instead of having her learn about her world gradually, as the result of conflicts and adventures, he has adult characters lecture her about it—or resorts to summarizing the backstory himself. This first chapter is 30 pages of almost pure info dump, along the lines of “A strip of the vanquished kingdom, up against the eastern edge of the mountains that the Narsils called the Northwest Chain and the Brethon called the Yrghaem, would pass into the empire’s hands. From Naesen’yr to the mines of Braoghein, the eastern marches of Capaelya were the empire’s now.”

And contrasts how George R.R. Martin introduced his characters in A Game of Thrones (the book). There’s nothing here particularly about how this fantasy is any kind of Christian allegory. She concludes,

Douthat admits in his Substack post that The Falcon’s Children is “rather fat, overly ambitious, probably-undercooked,” and that he doesn’t really have the time for “long experiments.” Fair enough. If the rest of the novel is like Chapter 1, it needs to be rewritten from top to bottom, and that’s a daunting task for someone with a day job, even one as seemingly cushy as New York Times columnist. Nevertheless, The Falcon’s Children has promise. Yes, I was annoyed all through Chapter 1 that Douthat wasn’t continuing the story of Ylaena and her changeling twins, but then the single most important thing a genre novelist can do is make the reader want to know what happens next. Ross, you can do that! You just have to remember to keep doing it for hundreds of pages. It will mean long years of struggle and toil, but for a tortured Christian moralist, isn’t that a plus?

\\

In contrast is one modern day fantasy writer appreciating one of the greatest fantasy (and SF) writers of all time.

Lithub.com, Kelly Link, 31 Jan 2023: Kelly Link in Praise of Ursula K. Le Guin’s Genuine Magic, subtitled “It is striking how resonant Le Guin’s work remains even as the future she describes recedes into our past.”

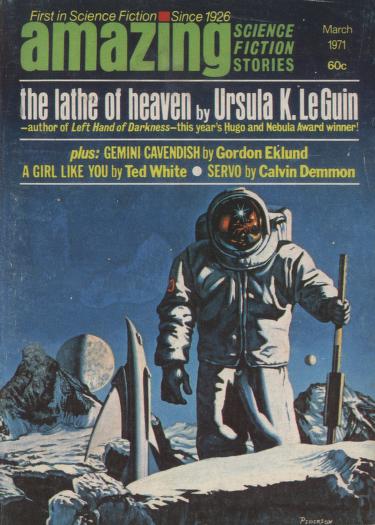

This is written on the occasion of a new edition, by Scribner’s, of Le Guin’s 1971 novel The Lathe of Heaven, a Philip K. Dickian novel about a man whose dreams change the world.

What struck me is the same thing that’s struck me about the many Library of America editions of Fantasy, Science Fiction, & Horror novels and stories, that so many of them were first published in what were then and what seem even now to be “trashy” magazines of presumed sub-literary content. Link begins thus:

Originally, The Lathe of Heaven appeared in two installments in Amazing Stories, a pulp magazine started in 1926 by Hugo Gernsback. Ursula Le Guin, born in 1929, read Amazing Stories as a child and would go on to outlive almost all the science fiction pulp magazines. While many of the writers Gernsback introduced to the field have fallen out of fashion and been forgotten, Le Guin’s influence has expanded beyond all original bounds of genre, appropriately so, as her writing was profoundly slippery, generous, shape-shifting, and outreaching from the very start.

Here’s what Amazing Stories looked like for March 1971, when it published the first half of Le Guin’s novel.

Not too trashy, actually, compared to the pulp magazines of 30 years before.

Link goes on with a fine encomium to this Le Guin novel — a novel I confess, having reread it only two years ago, I’ve always found rather flat. No gorgeous Le Guin prose; ideas familiar from many other writers. (In fact, the core idea, minus rationalizations, of how people create new worlds with their minds, is exactly like the Lanza/Kress novel reviewed here recently. The rationalizations change.)

But this is an example of how literary reputations form. Prolific writers, even if they borrow ideas from other writers, can get credit for those ideas, because they are remembered and the other writers are not. (Though of course PKD has gotten his share of Library of America attention.)

\\\

Two quick notes, observations and insights about recent reading. Very quickly, since I’m running late; perhaps I’ll expand on these later. First: Robert A. Heinlein’s Tunnel in the Sky can be read as a response to William Golding’s Lord of the Flies.

Second, following up on my mention of the John Brockman book The Third Culture, I should note that Brockman has done a series of trade paperback anthologies over the past 20 years that are similar collections of short essays by esteemed scientists and philosophers, with titles like This Will Change Everything: Ideas That Will Shape the Future, This Explains Everything: Deep, Beautiful, and Elegant Theories of How the World Works, and This Idea is Brilliant: Lost, Overlooked, and Underappreciated Scientific Concepts Everyone Should Know. It struck me today that for anyone trying to understand the modern scientific take on the world, Brockman’s nonfiction anthologies are better accesses to these ideas than trying to track down all the many books by the authors he samples. (I have half a dozen of these Brockman anthologies, but not all.)