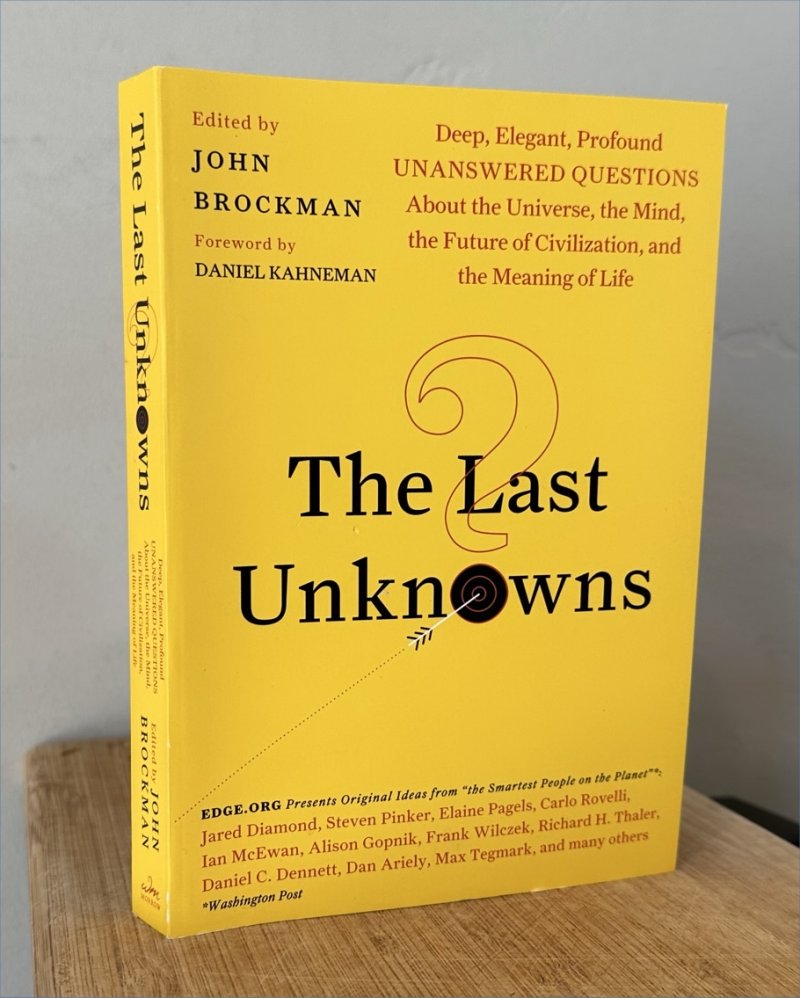

When I was browsing through several John Brockman books a few weeks ago, I decided to buy the last one he published in that series, from 2019. It’s called The Last Unknowns, and instead of gathering answers from many contributors to a single question for each book, this one is a collection of questions, the deepest, most profound questions that remain unanswered, according to the contributors. Just questions.

Typically there’s one question per contributor on each page. So you can flip through the book in about a hour. In this and a subsequent post or two, I’ll list what I think are the most interesting questions, and then give my take on the nature of their answers.

The book is 325 pages long, plus index. A few contributors get two pages, either because their questions seem especially profound (to Brockman, presumably), or perhaps just to break up the monotony of the book’s format. Thus there are fewer than 325 contributors, perhaps 250. In the first 100 pages or so, I noted these 19.

Alun Anderson, p4: Are people who cheat vital to driving progress in human societies?

This goes to the idea that certain human emotions, like the ability to identify and discourage cheaters, is built into human nature. That cheaters never go away… suggests that they do contribute in some indirect manner to human progress. Maybe by keeping people on their toes, so to speak.

Samuel Arbesman, p7: How do we best build a civilization that is galvanized by long-term thinking?

This goes to the inability of so many people to anticipate long-term consequences, and the recent trend of “longtermism” that tries to counter that problem. As with the Age of Reason (see Brian Eno below) I doubt more than a small fraction of the population will ever care about either long-term thinking, or reason. Most people are happy to live their day to day lives and let other people address long-term problems.

Simon Baron-Cohen, p15: Can we re-design our education system based on the principle of neurodiversity?

Baron-Cohn wrote The Pattern Seekers, about the benefits of autism, which I reviewed here. He describes a few things already being done along this line.

Gregory Benford, p20: What is the hard limit on human longevity?

The answer seems to be somewhat more than a century, but not forever. Benford (the science fiction writer) has been active in developing life-extension technologies.

Paul Bloom, p26: Why are we so often kind to strangers when nobody is watching and we have nothing to gain?

A huge issue of human evolution, which has mostly been solved: altruism, even among non-family members, as a component the prerequisite of culture.

Nick Bostron, p31: Which questions should we not ask and not try to answer?

Bostron writes about superintelligence and is associated with the longtermism folks; his question evokes the “there are some things man was not meant to know” trope of those hostile to science. Still, see Jerry Coyne below.

David Chalmers, p39: How can we design a machine that can correctly answer, every question, including this one?

A question we can ask the new AI apps (this book was compiled in 2019), which they probably can’t answer, because they reflect everything they’ve absorbed from the internet, true and untrue.

David Christian, p45: Will we pass our audition as planetary managers?

Christian is a leader in the “Big History” movement.

George Church, p26-27: What will we do as an encore once we manage to develop technological solutions to infection, aging, poverty, asteroids, and heat death of the universe?

Conservatives won’t believe them, or take them, or understand them, or care. Only that same small population will notice or care. (See Arbesman and Eno.)

Jerry A. Coyne, p52: If science does in fact confirm that we lack free will, what are the implications for our notions of blame, punishment, reward, and moral responsibility?

Most people won’t believe it and will continue to behave as if we do have free will, as an illusion that might be worth keeping.

Oliver Scott Curry, p56-57: Why be good?

Don’t know this contributor. The answer, basically, is that social and individual health is promoted by being more good than bad. People who are consistently bad don’t survive as often.

Stanislas Dehaene, p61: Is our brain fundamentally limited in its ability to understand the external world?

Don’t know this contributor. The answer is probably yes, with quantum mechanics as exhibit A. This is an area that science fiction teases at; would alien intelligences be able to comprehend the world in ways humans cannot?

Daniel C. Dennett, p62-63: How can an aggregation of trillions of selfish, myopic cells discover the unwitting teamwork that turns that dynamic clump into a person who can love, notice, wonder, and keep a promise?

I have several of Dennett’s books, and reviewed this one. The answer will have to be something about understanding the nature of emergence — how masses of small things that we do understand in detail can combine into larger systems that cannot be understood in the same way.

David Deutsch, p66: Are the ways qualia relate to computation, creativity to free will, risk to probability, morality to epistemology, all the same question?

I reviewed this Deutsch book, which made the case that a small number of high-level theories are in fact analogous in significant ways. So the answer is probably yes, at some level, if only because there are only a certain number of ways to arrange or relate fundamental concepts.

Jared Diamond, p68: Why is there such widespread public opposition to science and scientific reasoning in the United States, the world leader in every major branch of science?

Diamond is the author of Guns, Germs, and Steel, of course. The answer is probably the oddly tenacious hold that religion still has on Americans, in contrast to other highly developed nations. And it’s only a small minority of Americans leading all those branches of science.

Nick Enfield, p77: Is the accumulation of shared knowledge forever constrained by the limits of human language?

Probably, for reasons similar to Dehaene’s concern. Also relevant is how many languages (e.g. Japanese) have peculiar concepts that don’t exist in other languages.

Brian Eno, p78: Have we left the Age of Reason, never to return?

Probably better to wonder to what extent, i.e. how much of the world population, ever experienced it in the first place. As long as technological civilization exists, it will remain to some extent, at least for those who understand the world and make it work.

Helen Fisher, p86-87: What will courtship, mate selection, length of marriages, and family composition and networks be like when we are all living over 150 years?

They’ve already been changing since life expectancy began lengthening over the past couple hundred years with the development of modern medicine. Life-long marriages will become less common, and traditional family structures will relax, try as the conservatives strive to institutionalize the old ways into law.

Alison Gopnik, p104-105: How can the few pounds of grey goo between our ears let us make utterly surprising, completely unprecedented, and remarkably true discoveries about the world around us, in every domain and at every scale, from quarks to quasars?

Because the universe is natural (not supernatural) and works to repeatable principles; our brains necessarily evolved to live in a world with such principles and patterns; also, the same as Daniel Dennett’s issue above.