Two items today

- How Big Oil uses “red herring” issues to deflect attention away from the big issue

- Ted Chiang on the potential corrosive effect of AI on capitalism

Plus, a brief reflection on the SF writers who’ve had things to say about their contemporary world.

Salon, Kathleen Dean Moore, 13 May 2023: How Big Oil is manipulating the way you think about climate change, subtitled “A logic professor explains how a persistent, subtle fallacy has infected public discussion of climate change”

Will this can’t be a new story; what fallacy does this professor link it to?

In medieval times, gamekeepers trained dogs to the hunt by setting them on the trail of a dead rabbit they had dragged through the forest. Once the dogs were baying along the rabbit’s scent, the gamekeeper ran across the trail ahead of them, dragging a gunny sack of red herrings. Red herrings are smoked fish that have been aged to a ruddy, stinking ripeness. If any dog veered off to follow the stench of the red herrings, the gamekeeper beat him with a stick. Thus did dogs learn not to be lured into barking up the wrong tree.

This practice became the namesake of one of the best-known types of fallacies, the red herring fallacy. As a philosophy professor, this is how I explain the fallacy to my students: If the argument is not going your opponent’s way, a common strategy — though a fallacious and dishonorable one — is to divert attention from the real issue by raising an issue that is only tangentially related to the first.

Well that’s interesting — the derivation of the phrase “red herring.”

If our collective philosophical literacy were better, we might notice that this fallacy seems to be working spectacularly well for the fossil-fuel industry, the petrochemical industry, and a bunch of other bad actors who would like to throw us off the trail that would lead us fully to grasp their transgressions. We shouldn’t keep falling for it.

He gives examples.

- The train derailment in Ohio raised issues about railroad safety; the concerns should have been about the use carcinogenic chemicals.

- Another: Passing laws against new natural gas infrastructure. (The writer mentions Eugene, Oregon, but Berkeley CA has floated the idea too.) The red herring concern is gave vs. electrical stoves. The real issue is the continued support of the fossil fuel industry and the need to just stop burning fossil fuels.

- Another: Carbon sequestration. The real concern should be to simply stop burning fossil fuels.

- Another: Calculations of carbon footprints. This is Big Oil making it *our* problem, not theirs; individual efforts are minuscule.

- Another: debates at the UN Climate Change Conference about relatively trivial issues like compensation for countries harmed by climate change, when the real issue is transitioning as quickly as possible away from a fossil fuel economy.

Finishing:

You have to be alert and you have to be smart, I tell my students, because the people who would deceive you are sophisticated professionals. But the pros are making a serious mistake, and that is to assume that the average American is not much smarter than a Cocker Spaniel, and so can easily be misled. The work ahead is to prove them wrong.

But they’re not wrong, especially when one political party is essentially united against expertise and anyone telling them what they need to do, to save the planet or anything else.

\\

The New Yorker, Ted Chiang, 4 May 2023: Will A.I. Become the New McKinsey?, subtitled “As it’s currently imagined, the technology promises to concentrate wealth and disempower workers. Is an alternative possible?”

Another piece by Ted Chiang! Before reading: the issue perhaps is that pondered by Yuval Noah Harari, about how AI or one sort another will put people out of work and who will therefore need to find other things to do. And who is McKinsey?

Chiang recalls the Midas parable and its true meaning (greed, not careful wording). Then.

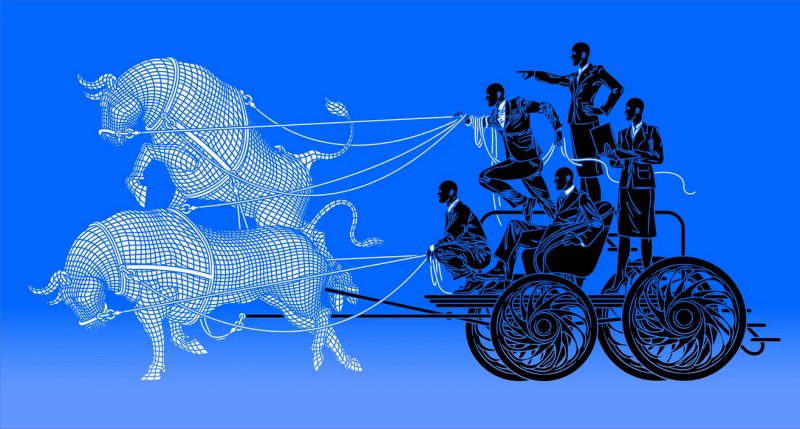

So, I would like to propose another metaphor for the risks of artificial intelligence. I suggest that we think about A.I. as a management-consulting firm, along the lines of McKinsey & Company. Firms like McKinsey are hired for a wide variety of reasons, and A.I. systems are used for many reasons, too. But the similarities between McKinsey—a consulting firm that works with ninety per cent of the Fortune 100—and A.I. are also clear. Social-media companies use machine learning to keep users glued to their feeds. In a similar way, Purdue Pharma used McKinsey to figure out how to “turbocharge” sales of OxyContin during the opioid epidemic. Just as A.I. promises to offer managers a cheap replacement for human workers, so McKinsey and similar firms helped normalize the practice of mass layoffs as a way of increasing stock prices and executive compensation, contributing to the destruction of the middle class in America.

He identifies the issue as that of A.I. [this seems to be New Yorker‘s house style for what many of the rest of us just style as “AI”] exacerbating the worst effects of capitalism. AI is like McKinsey, to which responsibility for making things worse can be passed off to.

Suppose you’ve built a semi-autonomous A.I. that’s entirely obedient to humans—one that repeatedly checks to make sure it hasn’t misinterpreted the instructions it has received. This is the dream of many A.I. researchers. Yet such software could easily still cause as much harm as McKinsey has.

[…But] It will always be possible to build A.I. that pursues shareholder value above all else, and most companies will prefer to use that A.I. instead of one constrained by your principles.

He gets around to the Harari notion.

Many people think that A.I. will create more unemployment, and bring up universal basic income, or U.B.I., as a solution to that problem. In general, I like the idea of universal basic income; however, over time, I’ve become skeptical about the way that people who work in A.I. suggest U.B.I. as a response to A.I.-driven unemployment. It would be different if we already had universal basic income, but we don’t, so expressing support for it seems like a way for the people developing A.I. to pass the buck to the government. In effect, they are intensifying the problems that capitalism creates with the expectation that, when those problems become bad enough, the government will have no choice but to step in. As a strategy for making the world a better place, this seems dubious.

Then discusses a notion I hadn’t heard of before.

You may remember that, in the run-up to the 2016 election, the actress Susan Sarandon—who was a fervent supporter of Bernie Sanders—said that voting for Donald Trump would be better than voting for Hillary Clinton because it would bring about the revolution more quickly. I don’t know how deeply Sarandon had thought this through, but the Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek said the same thing, and I’m pretty sure he had given a lot of thought to the matter. He argued that Trump’s election would be such a shock to the system that it would bring about change.

What Žižek advocated for is an example of an idea in political philosophy known as accelerationism. There are a lot of different versions of accelerationism, but the common thread uniting left-wing accelerationists is the notion that the only way to make things better is to make things worse. Accelerationism says that it’s futile to try to oppose or reform capitalism; instead, we have to exacerbate capitalism’s worst tendencies until the entire system breaks down. The only way to move beyond capitalism is to stomp on the gas pedal of neoliberalism until the engine explodes.

Chiang expresses his doubts about this strategy: “things can get very bad, and stay very bad for a long time, before they get better.”

And then corrects the common idea about “Luddites,” a corrective I’ve seen before.

People who criticize new technologies are sometimes called Luddites, but it’s helpful to clarify what the Luddites actually wanted. The main thing they were protesting was the fact that their wages were falling at the same time that factory owners’ profits were increasing, along with food prices. … The Luddites did not indiscriminately destroy machines; if a machine’s owner paid his workers well, they left it alone. The Luddites were not anti-technology; what they wanted was economic justice. … The fact that the word “Luddite” is now used as an insult, a way of calling someone irrational and ignorant, is a result of a smear campaign by the forces of capital.

The article goes on, to considerable but fascinating length. A couple more quotes.

Today, we find ourselves in a situation in which technology has become conflated with capitalism, which has in turn become conflated with the very notion of progress. If you try to criticize capitalism, you are accused of opposing both technology and progress. But what does progress even mean, if it doesn’t include better lives for people who work? What is the point of greater efficiency, if the money being saved isn’t going anywhere except into shareholders’ bank accounts?

*

The only way that technology can boost the standard of living is if there are economic policies in place to distribute the benefits of technology appropriately. We haven’t had those policies for the past forty years, and, unless we get them, there is no reason to think that forthcoming advances in A.I. will raise the median income, even if we’re able to devise ways for it to augment individual workers. A.I. will certainly reduce labor costs and increase profits for corporations, but that is entirely different from improving our standard of living.

*

The essay ends:

The tendency to think of A.I. as a magical problem solver is indicative of a desire to avoid the hard work that building a better world requires. That hard work will involve things like addressing wealth inequality and taming capitalism. For technologists, the hardest work of all—the task that they most want to avoid—will be questioning the assumption that more technology is always better, and the belief that they can continue with business as usual and everything will simply work itself out. No one enjoys thinking about their complicity in the injustices of the world, but it is imperative that the people who are building world-shaking technologies engage in this kind of critical self-examination. It’s their willingness to look unflinchingly at their own role in the system that will determine whether A.I. leads to a better world or a worse one.

\

With Ted Chiang providing technological commentary recently, I pause to wonder, who are the science fiction writers who’ve had intelligent things to say about their modern world? Decades ago we had Asimov and Clarke, who published essays in mainstream media about the impacts of technology. Lately we’ve had David Brin for some time, with many opinions about everything but especially politics (see here); and we’ve had Cory Doctorow for as long or longer (with bimonthly columns in Locus Magazine. And now we have Ted Chiang, who’s publishing in higher-profile venues (The New Yorker!) than any of those others ever did, or have.