Two items today.

- How Republicans are determined to impeach President Biden, despite lack of any evidence of his committing any crime (in striking contrast for former president Trump);

- How many people think crime is worse than ever, and the economy is worse than ever, despite evidence otherwise.

Ideology is easy; drawing conclusions from evidence is hard. Politics is easy; solving problems is hard. Religion is easy; science is hard. Fantasy is easy; (honest) science fiction is hard. (By “hard” I mean difficult, but of course that word has a particular meaning when discussing science fiction.)

NY Times, David French, 12 Sep 2023: Where Is the Evidence, Speaker McCarthy?

There is a certain pattern to modern impeachment inquiries. They typically begin after the discovery of blatantly incriminating evidence. In 1998 the House of Representatives began its impeachment inquiry only after DNA tests on Monica Lewinsky’s blue dress exposed that Bill Clinton had lied under oath about their affair.

In 2019 the House opened its impeachment inquiry only after it received reports that Donald Trump had attempted to coerce President Volodymyr Zelensky of Ukraine into investigating Trump’s chief domestic political opponent. The day after Nancy Pelosi announced the inquiry, the White House released a rough transcript of Trump’s call with Zelensky, and Americans could see that Trump did indeed press Zelensky to investigate Joe Biden, as a “favor” in response to Ukraine’s request for Javelin anti-tank missiles.

And we all know what happened after Jan. 6, 2021. The House initiated the second impeachment of Trump only after his weekslong festival of lies about election fraud culminated in a violent attack on the Capitol.

On Monday, House Speaker Kevin McCarthy ordered the House Oversight, Judiciary and Ways and Means Committees to start an impeachment inquiry into Biden without anything approaching comparable evidence. Indeed, the absence of such evidence was used as a perverse justification for the impeachment inquiry. The pretext is the purported need to grant greater investigatory authority to House committees examining whether Biden lied about his business dealings with his son Hunter and whether the president granted Hunter “special treatment” in the ongoing criminal investigation of Hunter’s potential tax and gun crimes.

But at the risk of sounding crass, where is the blue dress? Where is the phone call? Where is the riot? There’s little question that Biden family members — especially Hunter but also Joe Biden’s brother James and daughter-in-law Hallie — have profited enormously over the course of Joe Biden’s political career. But evidence that the president was himself involved in Hunter’s schemes or shared in any of the profits is thus far lacking, as is any evidence that the president violated the law.

I’ve noted this many times: conservatives don’t do evidence. They seem unable to draw conclusions from evidence; they already have their conclusions, based on ideology. They have no interest in attempting to solve any actual problems, which they routinely deny exist (e.g. climate change).

\\

Another ongoing story, in this example with data graphs. (It’s a subscriber-only post, but I can capture some of his graphics and embed them here.)

Paul Krugman, NY Times, 12 Sep 2023: Crime, Inflation and Public Perceptions

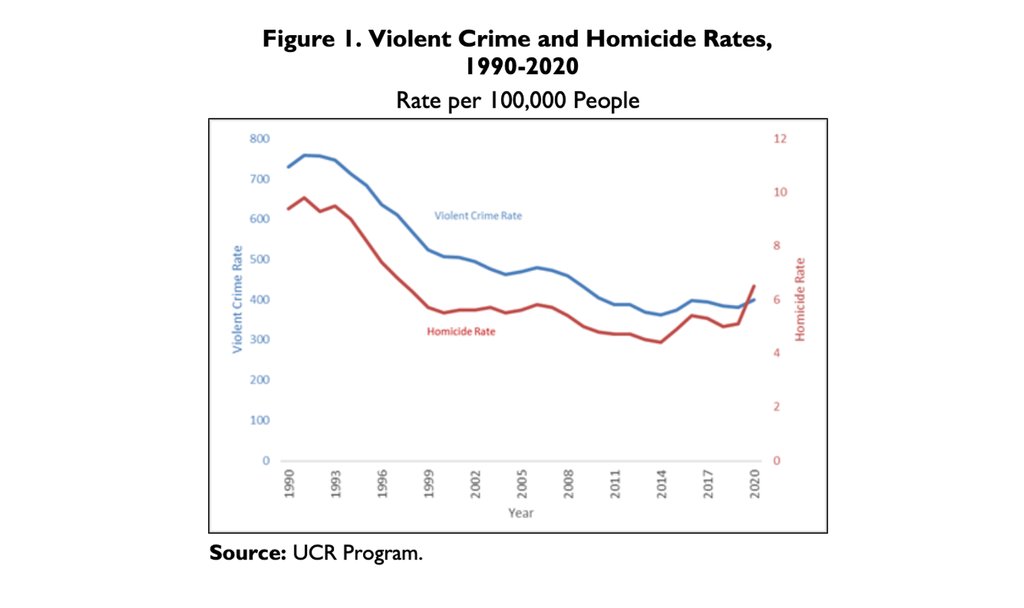

Again, the gist of this is that many people *believe* crime is worse than ever even though statistics say it is not. Crime peaked in the 1990s, and has dropped every since, except for an uptick due to the pandemic.

A key here:

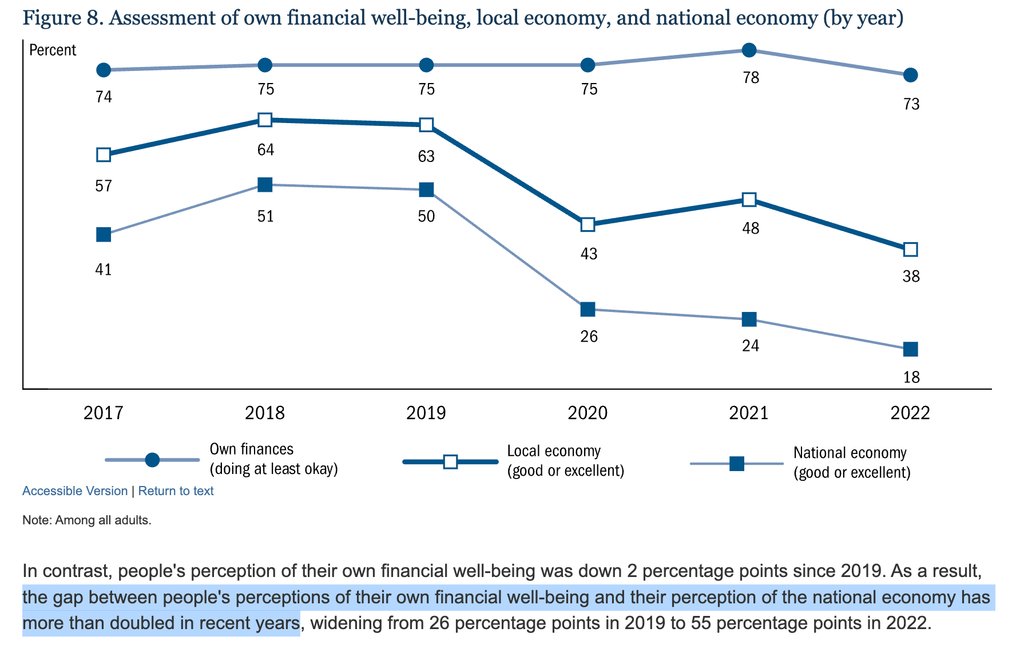

Why am I talking about public perceptions of crime? Well, last week, I wrote about the gap between public perceptions of a terrible economy and the reality of an economy that is doing very well by normal standards. I also noted that Americans seem relatively upbeat about their own financial circumstances; they just think that bad things are happening to other people.

People think their personal circumstances are OK; but bad things are happening everywhere. This is a psychological issue with people who don’t understand evidence and conclusions. Then Krugman makes an interesting admission about his circumstances writing for the NY Times, and identifies a key reason people believe what they do: they simple don’t have time to pay attention to anything other than what their social networks are telling them. I agree with that, and I may have said it before.

Not surprisingly, I got a lot of pushback. That’s OK; after all these years writing for The Times I have a pretty thick skin, although I have to admit to being annoyed at pundits who try to cut off discussion by asserting that anyone who questions widely held beliefs is an “elitist” who thinks Americans are stupid. For the record, I don’t think Americans are stupid. I think they have jobs to do and children to raise and lives to live. They don’t have time to study policy issues, so most of them get their sense of what’s happening to the country from what they see on TV or hear from politicians. Unfortunately, some of what they’re told isn’t true.

He then goes on to address views about the economy, and again, most people think their own situation is OK, but that the economy in general is in shambles (despite all the evidence).

So why do people believe that the state of the economy, or crime rates, are so much worse around the country than what they personally experience? Because politics. Someone’s lying. And who would be lying? Well, perhaps the party whose beliefs are most out of step with the evidence, with reality.

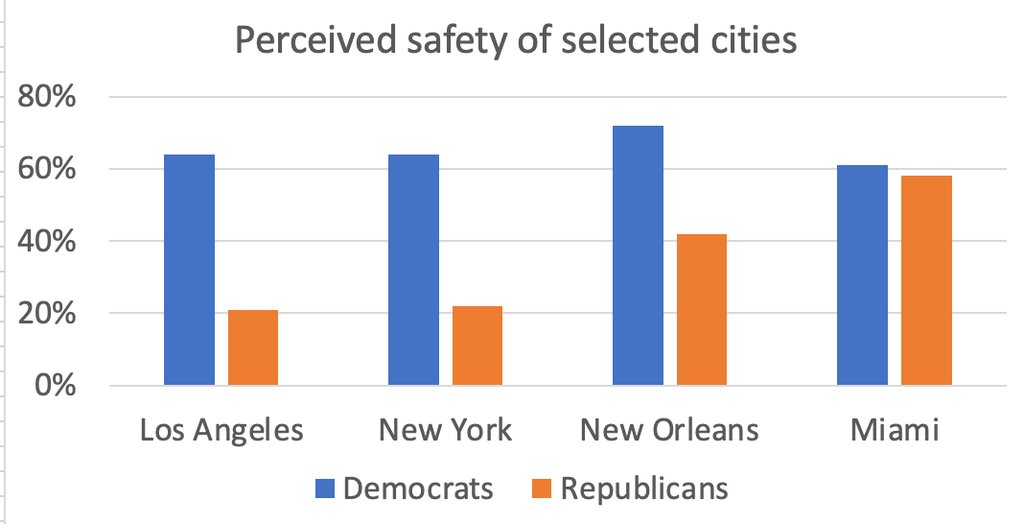

And there are huge partisan gaps in assessments of how safe cities are:

Krugman finishes:

As it happens, the Republican perception of Los Angeles and New York as unsafe compared with southern cities is wildly off base. Both have low homicide rates — half as high as Miami’s — and New York City is overall one of the safest places in America.

What does all this tell us, besides the fact that Americans are very confused about crime? It shows that on an important public issue, people can hold beliefs about what is happening to other people — people who live in other places, or in the nation as a whole — that are not just false but also at odds with their personal experience.

Why should this kind of disconnect be restricted to crime? There are, in fact, strong reasons to believe that there’s a similar disconnect when it comes to the economy. And we shouldn’t be afraid to say that out of fear that we’ll be considered elitist.