- Looking at today’s Phil Plait column at Scientific American, about his responses to a 2001 Fox TV program that claimed the Apollo 11 Moon landing was a hoax;

- The history since then about so many other conspiracy theories;

- And how some conspiracy theories are driven by “personal incredulity,” a reliance on “common sense,” and an unwillingness to deal honestly with the real world.

Today, let’s mull on this piece by astronomer Phil Plait from his current gig as a columnist for Scientific American.

At least back in the 1970s you didn’t have politicians spouting conspiracy theories like this one.

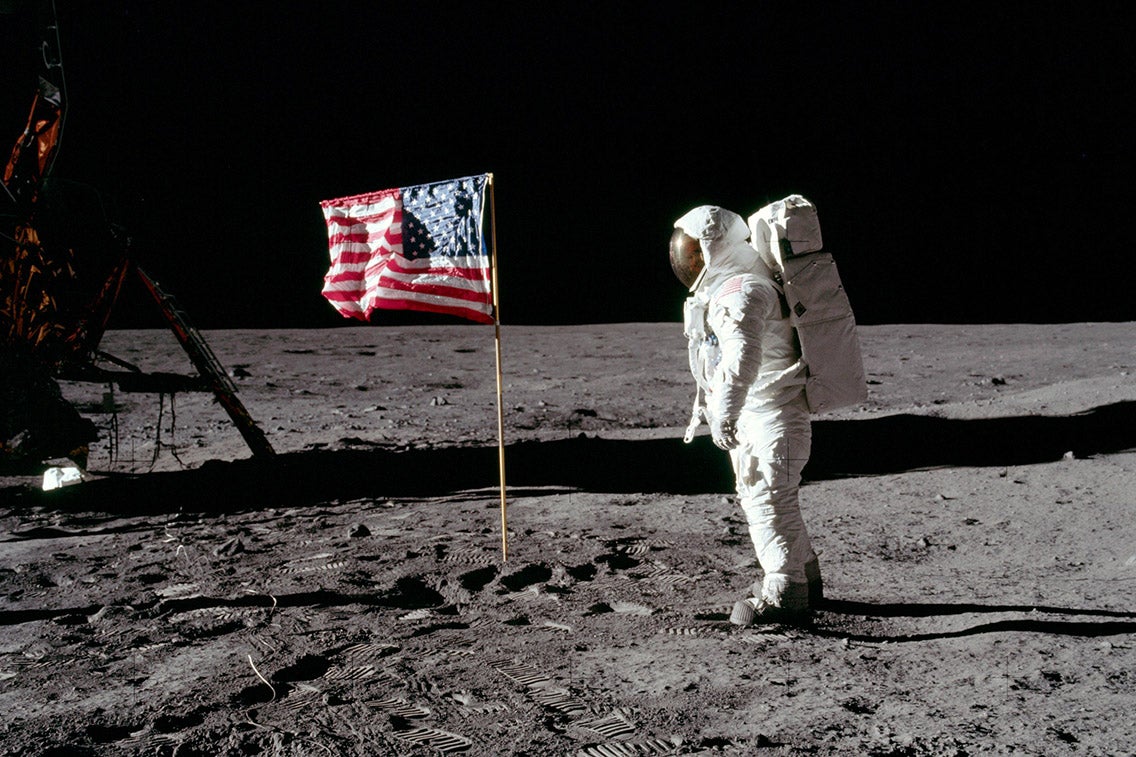

Phil Plait, Scientific American, 14 Sep 2023: Moon Landing Denial Fired an Early Antiscience Conspiracy Theory Shot, subtitled “Apollo moon landing conspiracy theories were early hints of the dangerous anti-vax, antiscience beliefs backed by politicians today”

Plait recalls seeing a 2001 TV program on Fox (of course!) called “Conspiracy Theory: Did We Land on the Moon?” (I’m even giving you the IMDb link). He’d just written a book, Bad Astronomy (which I reviewed here in 2022) covering the so-called moon-landing hoax, and many similar topics.

Plait recalls his initial reaction to the program:

I watched it with equal parts disdain, disgust and frustration. The claims made were nothing new, and laughably bad. The modus operandi of this conspiracy was to lay out a claim but give only a partial explanation of it, withholding the last bit of evidence needed to truly understand it; that way, you can “just ask questions” without having to go to the effort of actually answering them satisfactorily.

I sat down and wrote an article debunking the show point by point (warning: 1990s eye-straining Web layout at that hyperlink) and waited until after the show aired to post it online. The response was overwhelming: I received hundreds of emails, some supportive, many not so much (“crackpottery” is a term I prefer). I even heard from people at NASA thanking me, including from an Apollo astronaut who, I’ll note, actually had walked on the moon.

Online traffic to my review exploded. And it’s no exaggeration to say it helped launch my career as a science communicator and antiscience debunker. I went on to give public talks all over the world based on the ridiculous claims in the show.

But this came at a cost. The TV program was extremely popular, so much so that Fox re-aired it a few weeks later. I was extremely aggravated, as a space nerd and huge Apollo fan, to see one of the greatest achievements of our technological society dishonored in such a way.

Today, though, this conspiracy theory is mostly relegated to the waste bin; you hardly hear about it anymore. People have moved on.

Or have they? Via Facebook’s inscrutable algorithms, which seem to feed me a different selection of videos every day, I am *still* getting conspiracy theory posts about Apollo 11 and 9/11. They’re still out there.

Plait goes on. The problem is, since Apollo 11, there are always new conspiracy theories that pop up to replace the last one.

Even at the time, when I gave my talks mocking the show and the conspiracy theory, I was careful to note that this type of antiscience thinking is dangerous. What if a politician—many of whom are not known for their grasp of science—were to buy into this nonsense and waste a vast amount of taxpayer money and NASA’s time investigating it?

Thus: the “antivaccine nonsense.” The creationists and their “intelligent design” (with its “Bad logic and withholding of needed evidence in their claims”). Global warming. And Donald Trump, whose attacks on reality were so numerous they became nearly impossible to keep track of.

Conspiracy thinking necessarily turns the scientific process upside-down, making a conclusion first and then seeking evidence to support it, while ignoring or attacking any evidence against it. This mindset is ripe for shaping by political tribalism, which amplifies closed belief systems, inuring them from outside remediation. Cultlike behavior, such as that of the QAnon movement, may start as an outlier in such an environment but now we see it as everyday ideology from some members of Congress who were reelected in the midterms, showing that they still have support not only despite, but because of, what they believe and say. And do.

Obviously, believing that NASA faked the moon landings is not the cause of all these execrable and obviously false beliefs, but they go hand in hand. A willingness to believe claims without evidence, to dismiss expert experience, and to entertain conspiratorial ideas are all at play here, and smaller, more “fun” ideas like the Apollo hoax are a foot in the door to a universe of nonsense. They may seem harmless, but they lead nowhere good.

This is the nature of the razor-thin path of scientific reality: there’s a limited number of ways to be right, but an infinite number of ways to be wrong. Stay on it, and you see the world for what it is. Step off, and all kinds of unreality become equally plausible.

All familiar themes. I have three thoughts to add.

First, the appeal of conspiratorial thinking aside, some of them arise from the limited cognition of people whose inherited human nature was formed, over hundreds of thousands of years on the Savannah, to interpret the world at certain scales (everything to the horizon) and timespans (a generation or two, or perhaps whatever history is implied by the stories told of tribal ancestors). Learning that the world is a sphere, or that humans traveled to the Moon, simply breaks the cognitive intuitions of many people, who therefore simply refuse to believe it. This is a common psychological bias, called the “argument from personal incredulity.” It is something you have to get over, if you are interested in apprehending the real world rather than just conforming to the prejudices of your tribe/community/family. Wisdom is an individual project.

Second, that evidence and deduction reveals a world far vaster than our intuitions support, undermines most people’s reliance on “common sense.”

Third, there’s a new book (by Richard Haass) with the subtitle “The Ten Habits of Good Citizens.” The book goes to the idea that in addition to certain “rights” guaranteed citizens, through constitutions, perhaps citizens have certain responsibilities and obligations. My thought here doesn’t correspond exactly to anything in that book. Rather, my thought is that being a responsible citizen might entail dealing with the world honestly, and not being taken in by conspiracy theories. Buck up. Take the world as it is.