- Carlo Rovelli on science and art;

- Big Think on failed predictions;

- Immortality as a philosophical paradox;

- Michio Kaku on the four types of planetary civilizations.

NY Times, guest essay by Carlo Rovelli, 16 Oct 2023: The Secret to Unlocking One of the Universe’s Greatest Mysteries

Rovelli is the author of several short, elegant books about physics and cosmology. This essay is an excerpt from his latest. Black holes and white holes aside, what I like here are these paragraphs about science and art. He evokes the themes of E.O. Wilson’s “consilience,” which I also use in the essay I’m just finishing up about how science fiction, if sufficiently honest, is a kind of consilience. Insights into reality, the reality religion ignores in favor of narrative shellac over everything.

Anaximander left at home the idea that all things fall in the same direction: For the Earth itself not to fall, falling must be different than what we thought. Kepler left at home the idea that things move in circles, which seems so natural. Einstein left behind the idea that all clocks tick in tune with each other, which still seems obvious to many of us, and yet is wrong. If we leave too many things at home, we lack the tools needed to forge ahead; if we take too many, we fail to find the paths to new understanding. There are no recipes for success. There is only trial and error. Trying and trying again.

This is what we do, the long study and the great love that is scientific inquiry. We combine and recombine in different ways what we know, looking for an arrangement that clarifies something. We leave out pieces that previously seemed essential, if they get in the way. We take risks, albeit calculated ones. We linger at the border of our knowledge. We familiarize ourselves with it, and we spend a long time there, walking back and forth along its length, searching for the gap. We try out new combinations. New concepts.

I think that this is also how the best art works. Science and art are both concerned with the continual reorganization of our conceptual space, of what we call meaning. What happens when we react to a work of art is not happening in the art object itself, of course — still less in some unphysical “world of the spirit.” It lies in the complexity of our brain, in the kaleidoscopic network of analogical relationships with which our neurons weave what we call meaning.

We are involved, engaged — for this takes us out of our habitual sleepwalking, reconnecting us with the joy of seeing something anew in the world.

It is the same joy that science gives us. The light in a Johannes Vermeer painting opens our eyes to a resonance of light in the world that we had not previously been able to seize; a fragment of a poem by Sappho opens up a world in which to rethink desire; one of Anish Kapoor’s voids of pure black disorients us, like the black holes of general relativity. And like the latter, it suggests that there are other ways of conceptualizing the impalpable fabric of reality.

Between observation and understanding, the road can be long. Copernicus and Einstein, for instance, obtained their momentous results based on observations that had been well known in the past — in the case of Copernicus, for more than a millennium. It is the capacity to change the organization of our thoughts that allows us to make the leap.

\\\

Some more science-based, or at least reality-based, items for tonight.

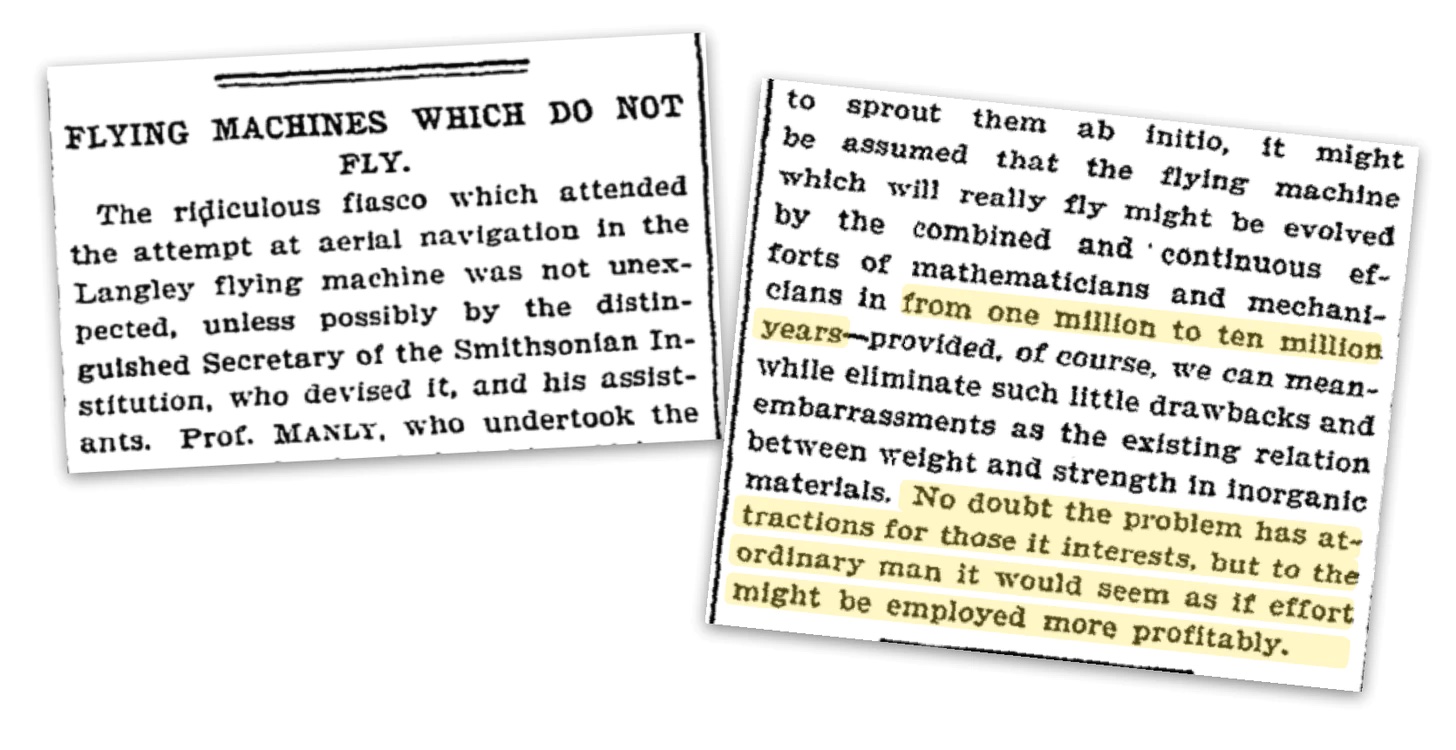

Big Think, Louis Anslow, 18 Oct 2023: In 1903, New York Times predicted that airplanes would take 10 million years to develop, subtitled “Only nine weeks later, the Wright Brothers achieved manned flight. The pathologically cynical always will find a reason to complain.”

Key Takeaways

• The media once deemed flight, both in air and space, impossible or an act of egotism. • Perhaps most infamously, the New York Times predicted that airplanes would take one to ten million years to develop. Merely nine weeks later, the Wright Brothers achieved manned flight. • The pathologically cynical always will find a reason to complain.

The article is a chronology of failed predictions that air flight and space flight were impossible, including the famous “Space travel is utter bilge” comment from 1955 — from the British Royal Astronomer. Another piece, opposing the “Moondoggle” of the 1960s, was by Russell Kirk, a prominent conservative who also dabbled in science fiction and fantasy. Arthur C. Clarke covered such topics in his book Profiles of the Future, published 1962 and revised several times, which I reviewed here.

My take, that the article doesn’t mention, is that these failed predictions were outliers. That’s why they’re still news 50 and 100 years later. At the same time, they’re evidence of human biases toward the familiar; people have difficulty believing that things can change, that the future will not be like the present, that the actual universe is quite different from local surroundings.

\\

Big Think, Scotty Hendricks, 16 Oct 2023: 5 philosophical problems with immortality, subtitled “Is immortality a tantalizing possibility or a philosophical paradox?”

Key Takeaways

• The idea of living forever is attractive, but does it make any philosophical sense? • There are more than a few philosophical problems with immortality and the ways some people think it works. • The nature of identity is central to understanding immortality: Does the same “self” persist after death, and what truly defines us?

The five: What is death?; What is immortality, anyway?; What gets to live forever?; What are we made of?; Weak arguments.

My take: I don’t believe in life after death, or immortality, and I think those who do haven’t thought this through. Living forever *how*? In what circumstances? On a cloud in Heaven? Really?? With how many of your deceased relatives? All of them? In what condition? Walking along a beach (as at the end of Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life)? And then what? Wouldn’t whatever it is become eternally boring??

Life is a process, with progress, and in fantasy Heaven there can be no progress, because everything is eternal. And thus boring.

\\

Big Think, Michio Kaku, 17 Oct 2023: The four types of planetary civilizations, explained by Michio Kaku, subtitled “Humanity is a type 0 civilization. Here’s what types 1, 2, and 3 look like, according to physicist Michio Kaku.”

Like many of the pieces on this site, this is a summation of work done earlier by others.

Type one would be planetary: They control the weather. They control anything planetary because they have the energy of a planet.

Then there’s type two: A type-two civilization has exhausted the power of their planet and they use the sun. They basically take the energy from their sun to power their machines, sort of like the Federation of Planets in “Star Trek.”

Then there’s type three: Galactic. They roam the galactic space lane, they play with black holes, sort of like the Empire of “Empire Strikes Back.” That would be a type-three civilization.