There have been several articles recently about how, and why, economists think the economy is doing just fine, while ordinary people (voters) don’t. Why would this be? Are these ordinary people simply poisoned by partisan propaganda? Or is it something deeper? A couple substantial ideas show up, among four pieces examined here.

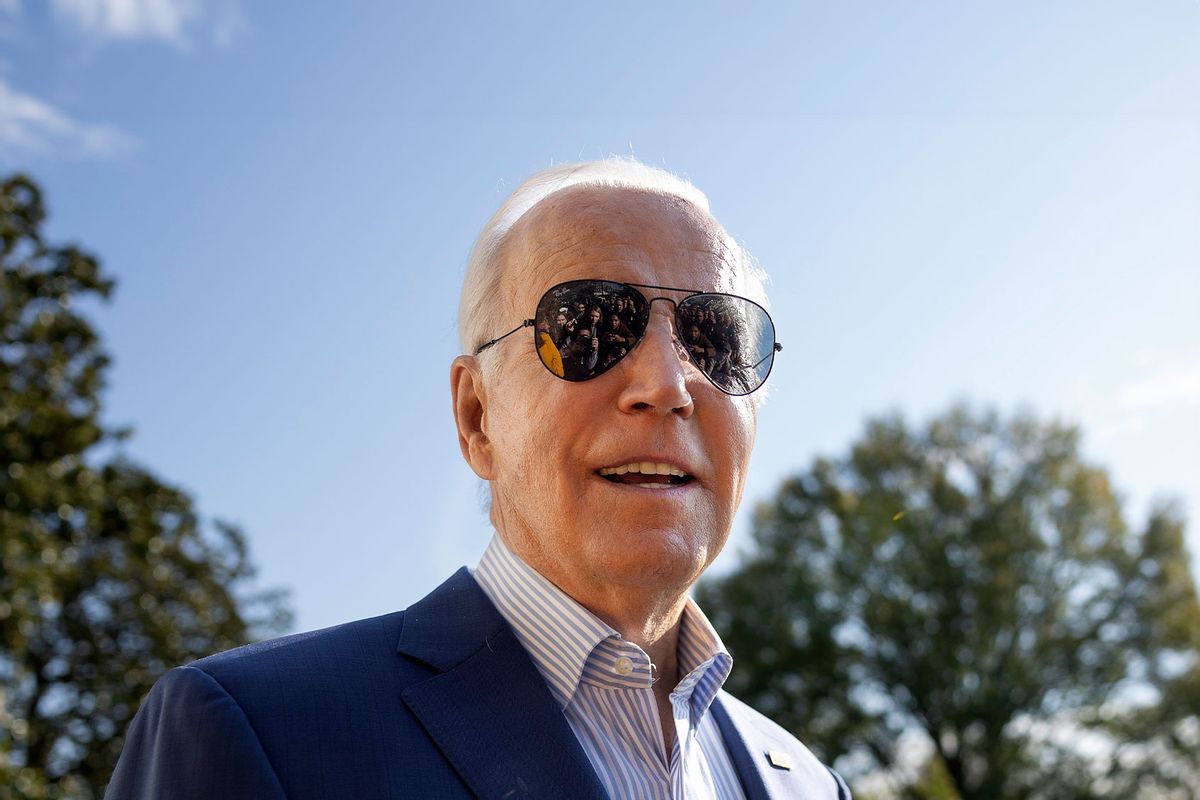

Salon, Kirk Swearingen, 13 Nov 2023: Joe Biden’s economy is, honestly, pretty amazing: How come he doesn’t get credit?, subtitled “Many voters claim Biden’s economy is bad and Trump’s was better. What fantasy version of America do they live in?”

This writer considers his own personal experience.

If the economy is so bad, why are shops and restaurants so packed?

I understand that anecdotal evidence is hardly worth mentioning, but it does make you wonder if people are as concerned about the prices of goods and services as polling data says they are. As you stand in line at that restaurant or circle the mall parking lot looking for a space, do you wonder about the disparity between what people apparently tell pollsters about the economy and what you can see with your own two eyes?

Could this be part of the answer? People nowadays don’t know a truly bad economy looks like? (Does anyone alive now remember the Depression? Or the sacrifices people made during World War II?) Could be.

Biden’s bad economy? What does that even mean? Never mind the lowest unemployment numbers in decades and the other telling economic data points: Just look around. Even the Murdoch-owned Wall Street Journal acknowledges how strong the economy has been under this president:

Not only has economic output made up all the ground lost during the pandemic but it is above where it would have been had the pandemic never happened, judging by what the Congressional Budget Office projected in early 2020.

So what gives? Why do so many people tell pollsters that they think Trump and the Republicans would do a better job with the economy when that has literally never been true in my lifetime? (When Republicans claim they’re great with the economy, there must be a “worthless statement clause” buried in the fine print.)

Some good lines:

Republicans tell people what they long to hear, while Democrats are forever hamstrung by trying to tell people what they need to hear in order to function as responsible citizens in a democracy. But busy, overworked, stressed-out people don’t want complexity, and most people have no abiding interest in politics. But they do crave neatly packaged explanations that blame their own problems, and the world’s, on somebody else.

So while Republican voters keep on complaining about the Biden economy, they also keep on consuming like mad. They don’t like the higher prices of the last few years, which is understandable enough, and it doesn’t matter to them that all industrialized countries saw similar rates of inflation during the post-pandemic recovery, or that the inflation rate in the U.S has come down faster than in most other countries.

More good stuff — sharp observations — throughout.

\\\

The Atlantic, James Surowiecki, 10 Nov 2023: Why Americans Can’t Accept the Good Economic News, subtitled “They’re better off but not feeling it—which could be a really big political problem.”

“Are you better off today than you were four years ago?” That question, first posed by Ronald Reagan in a 1980 presidential-campaign debate with Jimmy Carter, has become the quintessential political question about the economy. And most Americans today, it seems, would say their answer is no. In a new survey by Bankrate published on Wednesday, only 21 percent of those surveyed said their financial situation had improved since Joe Biden was elected president in 2020, against 50 percent who said it had gotten worse. That echoed the results of an ABC News/Washington Post poll from September, in which 44 percent of those surveyed said they were worse off financially since Biden’s election. And in a New York Times/Siena College poll released last week, 53 percent of registered voters said that Biden’s policies had hurt them personally.

As has been much commented on (including by me), this gloom is striking when contrasted with the actual performance of the U.S. economy, which grew at an annual rate of 4.9 percent in the most recent quarter, and which has seen unemployment holding below 4 percent for more than 18 months. But the downbeat mood is perhaps even more striking when contrasted with the picture offered by the Federal Reserve’s recently released Survey of Consumer Finances.

Concluding,

So, even allowing for the high inflation we saw in 2022, no one could really look at the U.S. economy today and say that the policy choices of the past three years made us poorer. Yet that, of course, is precisely how many Americans feel.

Although that pessimism does not bode well for Biden’s reelection prospects, the real problem with it is even more far-reaching: If voters think that policies that helped them actually hurt them, that makes it much less likely that politicians will embrace similar policies in the future. The U.S. got a lot right in its macroeconomic approach over the past three years. Too bad that voters think it got so much wrong.

\\\

Paul Krugman, NY Times, 9 Nov 2023: What History Tells Us About the Feel-Bad Economy

Biden is not, in fact, presiding over a bad economy. On the contrary, the economic news has been remarkably good, and history helps explain why.

Nonetheless, many Americans tell pollsters that the economy is bad. Why? I don’t think we really know; what we can say is that historical experience throws some cold water on one popular view about the sources of American discontent.

…

The simple reality of the past year or so is that America has accomplished what many, perhaps most, economists considered impossible: a large fall in inflation without a recession or even a big rise in unemployment. If you don’t trust me, listen to Goldman Sachs, which on Wednesday issued a report titled “The Hard Part Is Over,” noting that we’re managing to combine rapid disinflation with solid growth, and that it expects this happy combination — the opposite of stagflation — to continue.…

Yet voters aren’t happy. The most widespread story I’ve been hearing is that people don’t care about the fact that prices have been leveling off; they’re angry that prices haven’t gone back down to their prepandemic levels.

This makes some psychological sense, Krugman admits, but history does not support the idea.

This isn’t the first time we’ve seen a temporary surge in prices that leveled off but never went back down. The same thing happened after World War II and again during the Korean War, the latter surge being roughly the same size as what we’ve seen since 2020. Unfortunately, we don’t have consumer sentiment data for the 1940s, although some political scientists believe that the economy actually helped Harry Truman win his upset election victory in 1948. But we do have such data for the early 1950s, and it suggests that people were relatively upbeat on the economy despite higher prices. Why should this time be different?

Also, it seems worth noting that many voters have demonstrably false views about the current economy — believing, in particular, that unemployment, which is near a 50-year low, is actually near a 50-year high.

And he concludes,

So what’s actually going to happen in the next election? I have no idea, and neither do you. What I can say is that if you believe that Biden made huge, obvious economic policy mistakes and could easily have put himself in a much better position, you probably haven’t thought this thing through.

And this resonates with my thinking: most people simply don’t pay close attention, or think things through. And social media, and the disinformation merchants, have undermined many people’s trust in “official” sources (of economic news, in this case), and have driven them into tribal allegiances divorced from reality.

\\\

One more.

NY Times, Peter Coy, 8 Nov 2023: Why Voters Are So Down on the Biden Economy

The theme here, again, is that economists and ordinary people use the same terms to talk about different things. Also, the example the writer provides suggests how Republicans, as they pursue their culture wars, may be losing voters who resent attention to such matters.

Economists, meet Sara. She is in her early 50s, white, an office manager who lives in South Carolina and a Republican who is unenthusiastic about Donald Trump. When she thinks about the direction of the country right now, what she’s most worried about is the economy. And whom does she blame for the economy?

Politicians in Washington, D.C., collectively. They have lost sight of how we live and work as middle-class people. We can give free Narcan to whoever we want to in the parking lot of McDonald’s because they’re OD’ing, but we cannot get diabetic medication to those kids who did not choose to be diabetic. People are losing their jobs and can’t afford health care, and you’re going to legislate whether or not somebody can read a book?

There is a lot to unpack in that angry paragraph, which came from a focus group, convened in September by Times Opinion, of 13 Republican voters who are looking at candidates other than Trump. (More of their responses here.) On diabetic medication, for example, there’s actually good news. The Inflation Reduction Act capped the cost of insulin for Medicare recipients at $35 a month. Lilly, Novo Nordisk and Sanofi have cut prices for patients of all ages.

But the part I want to focus on is what Sara and other Americans who aren’t economists mean when they use terms like economy, inflation and unemployment.

It’s often not what economists mean. And I think the differences in perspective go a long way toward explaining why President Biden receives such poor marks on the economy despite strong growth in the country’s gross domestic product, as well as low unemployment and falling inflation.

The writer goes on with examples of this disconnect. Also this:

Pollsters have long observed that voters who are unhappy in general will tend to express unhappiness in every answer, and not attempt to make fine distinctions.

And

Trump may also be benefiting from rose-colored hindsight. More voters have a favorable impression of Trump’s overall record now (48 percent) than they did when he left office (38 percent), according to the ABC News/Washington Post poll.

A close-term example of the rose-colored past, that some imaginary utopia once existed that we should all return to. Things were better when my side won!

And

As for the decline in inflation that Biden brags about: Only 38 percent said they believed the official statistics, against 62 percent who didn’t.

That disbelief says a lot. I don’t think it’s entirely a measure of distrust in the statistical agencies. I think it’s deeper than that. People are saying that, for whatever reason, prices went up. And they’re saying they can’t make ends meet. Anyone who tries to tell them that inflation has fallen is going to be ignored, or worse. Which means the incumbent president is in a bad spot.

\\\

The grand theme here is that as the world has become more complex — over past centuries, and past decades since the 1960s for various reasons — more and more people deny or reject that complexity and retreat into fictitious simplicity. Which authoritarians, like Trump, who divide the world into black and white, provide.