- Comments about that article that distinguished between “liberals” and “progressives”;

- Yet another piece about how “voters feel one way about the economy but act differently”;

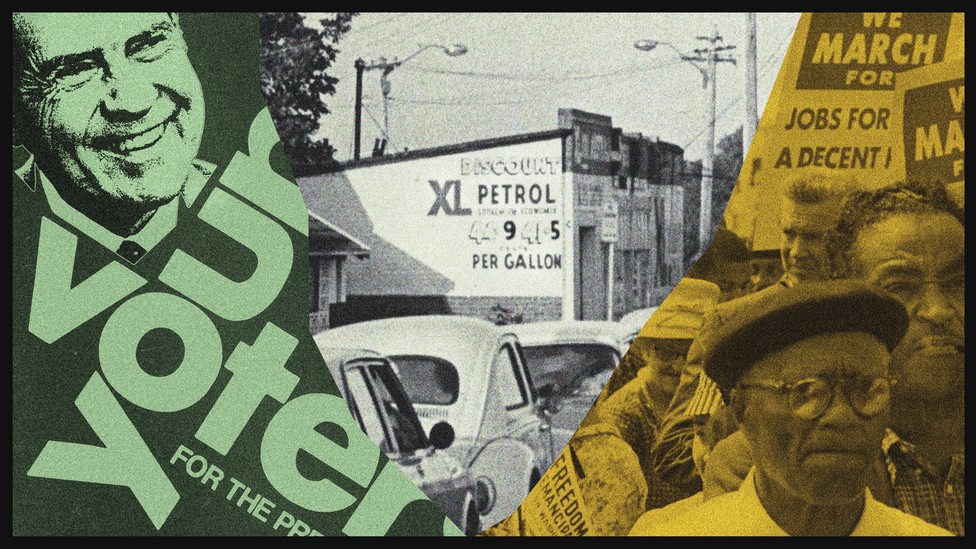

- An historical overview about how the US economy is no longer the greatest in history;

- Music from Radiohead: “There, there”. “Just ’cause you feel it, doesn’t mean it’s there.” Keying to a central theme on this blog.

Relatives in town for a busy Thanksgiving weekend, but I think I have an hour or two to post a few substantial items now.

NY Times, 23 Nov 2023, Letters: The Labels We Attach to Political Beliefs

These respond to the Pamela Paul essay I linked to eight days ago. Her take on liberals vs. progressive was that the former held to traditional liberal beliefs, while the “progressives” were driving the cancel culture from the left. Of these letters, here’s the one that most pertains to my theme about how these ideas are reflections of history.

To the Editor:

How about it doesn’t matter whether progressives are liberals? We must move beyond the old labels. We are separated by rationalists and irrationalists.

What was once liberal is simply (as it mostly always has been) common sense, common decency, and management of inevitable change for the benefit of the general welfare and liberty and justice for all. Basically, what any reasonable and broad view of society would see as doing the right thing.

Almost anyone’s reading of social and political history would agree that we live in a better, more decent and fair nation because of the right things that rationalists did: abolish slavery, rein in the robber barons, establish labor laws, and approve women’s suffrage, civil rights, voting rights, Social Security and Medicare. The right things to do, which the irrationalists opposed.

In this new century social attitudes have changed, geopolitical power has changed, technology has exploded, the climate has changed. But what hasn’t changed is the need and desire to do the right and decent thing. And there is only one side that continues that fight.

When we finally pull our heads above the surface of the water we’re swimming in, we might see that there is no longer a divide of right and left, red and blue, liberal and conservative; it’s one simply of right and wrong. Rationality vs. irrationality.

Lyndon Dodds

San Antonio

Except that I would not call them “irrationalists.” We are all a bit irrational at time, we can’t help it. I would call it realists vs. traditionalists. Or something along those lines.

\\

Yet another article about the the disconnect between how Americans feel about the economy, vs. how they personally behave.

NY Times, 20 Nov 2023: The Great Disconnect: Why Voters Feel One Way About the Economy but Act Differently, subtitled “Americans are angry and anxious, and not just about prices, which may be driving economic sentiment more than their financial situations, economists said.”

By traditional measures, the economy is strong. Inflation has slowed significantly. Wages are increasing. Unemployment is near a half-century low. Job satisfaction is up.

Yet Americans don’t necessarily see it that way. In the recent New York Times/Siena College poll of voters in six swing states, eight in 10 said the economy was fair or poor. Just 2 percent said it was excellent. Majorities of every group of Americans — across gender, race, age, education, geography, income and party — had an unfavorable view.

To make the disconnect even more confusing, people are not acting the way they do when they believe the economy is bad. They are spending, vacationing and job-switching the way they do when they believe it’s good.

Submitted as evidence. I’ve speculated about this divide before, but won’t just now.

\\

Here is a substantial piece that challenges my current go-to explanations for how politics changes in the 1960s, and how America’s economy has changed since then. (It’s not that I’ve been wrong, exactly, just incomplete.)

The Atlantic, Rogé Karma, 25 Nov 2023: Why America Abandoned the Greatest Economy in History, subtitled “Was the country’s turn toward free-market fundamentalism driven by race, class, or something else? Yes.”

A long piece that I will try to capture in a few quotes. The article opens with several paragraphs the lay out the issue and the competing answers.

If there is one statistic that best captures the transformation of the American economy over the past half century, it may be this: Of Americans born in 1940, 92 percent went on to earn more than their parents; among those born in 1980, just 50 percent did. Over the course of a few decades, the chances of achieving the American dream went from a near-guarantee to a coin flip.

What happened?

One answer is that American voters abandoned the system that worked for their grandparents. From the 1940s through the ’70s, sometimes called the New Deal era, U.S. law and policy were engineered to ensure strong unions, high taxes on the rich, huge public investments, and an expanding social safety net. Inequality shrank as the economy boomed. But by the end of that period, the economy was faltering, and voters turned against the postwar consensus. Ronald Reagan took office promising to restore growth by paring back government, slashing taxes on the rich and corporations, and gutting business regulations and antitrust enforcement. The idea, famously, was that a rising tide would lift all boats. Instead, inequality soared while living standards stagnated and life expectancy fell behind that of peer countries. No other advanced economy pivoted quite as sharply to free-market economics as the United States, and none experienced as sharp a reversal in income, mobility, and public-health trends as America did. Today, a child born in Norway or the United Kingdom has a far better chance of outearning their parents than one born in the U.S.

This story has been extensively documented. But a nagging puzzle remains. Why did America abandon the New Deal so decisively? And why did so many voters and politicians embrace the free-market consensus that replaced it?

Since 2016, policy makers, scholars, and journalists have been scrambling to answer those questions as they seek to make sense of the rise of Donald Trump—who declared, in 2015, “The American dream is dead”—and the seething discontent in American life. Three main theories have emerged, each with its own account of how we got here and what it might take to change course. One theory holds that the story is fundamentally about the white backlash to civil-rights legislation. Another pins more blame on the Democratic Party’s cultural elitism. And the third focuses on the role of global crises beyond any political party’s control. Each theory is incomplete on its own. Taken together, they go a long way toward making sense of the political and economic uncertainty we’re living through.

So: three ideas. I’ve been most attention to the first one. But the writer here provides some convincing arguments that, of course, real life is more complex than single explanations, and multiple explanations usually are necessary. On the third point, this is a factor not generally remembered — an example, as with current issues like gas prices, that politicians are not to blame for everything going wrong. There was another piece besides what the Republicans and Democrats did.

According to the economic historian Gary Gerstle’s 2022 book, The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order, that piece is the severe economic crisis of the mid-’70s. The 1973 Arab oil embargo sent inflation spiraling out of control. Not long afterward, the economy plunged into recession. Median family income was significantly lower in 1979 than it had been at the beginning of the decade, adjusting for inflation. “These changing economic circumstances, coming on the heels of the divisions over race and Vietnam, broke apart the New Deal order,” Gerstle writes. (Leonhardt also discusses the economic shocks of the ’70s, but they play a less central role in his analysis.)

Then as now, voters blame politicians for things that are outside the politicians’ control.

The piece also has this deep insight — essentially, about how Ronald Reagan was a brilliant politician. (Which is completely aside from whether he did good or bad.)

“Government is not the solution to our problem,” [Reagan] declared in his 1981 inaugural address. “Government is the problem.”

Part of Reagan’s genius was that the message meant different things to different constituencies. For southern whites, government was forcing school desegregation. For the religious right, government was licensing abortion and preventing prayer in schools. And for working-class voters who bought Reagan’s pitch, a bloated federal government was behind their plummeting economic fortunes. At the same time, Reagan’s message tapped into genuine shortcomings with the economic status quo. The Johnson administration’s heavy spending had helped ignite inflation, and Nixon’s attempt at price controls had failed to quell it. The generous contracts won by auto unions made it hard for American manufacturers to compete with nonunionized Japanese ones. After a decade of pain, most Americans now favored cutting taxes. The public was ready for something different.

\\\

Today’s music, again from Radiohead’s Hail to the Thief album. The song “There There”.

Key lyrics:

Just ’cause you feel it

Doesn’t mean it’s there

And

We are accidents

Waiting, waiting

To happen

We are accidents

Waiting, waiting

To happen