Late afternoon, Sunday of Thanksgiving weekend. Just finished putting lights up on our two second floor balconies, that should come on automatically an dusk. — 5:10pm, they’ve just come on. Oops, except for one string that came on only half-way. Sigh.

Beginning this post at 4:30pm to read some newspaper and web pieces I’ve captured links to but not yet read.

- Why George Santos and those like him lie about nonsense;

- How social media warps views about the American economy;

- How the culture war’s claims that comedy is being suppressed isn’t true;

- How young Americans don’t trust religion, or anything else;

- And listening to Radiohead’s In Rainbows.

NY Times, Elizabeth Spiers, 24 Nov 2023: The Very Good Reason People Like George Santos Lie About Nonsense

The gist: because you get so used to them lying about everything, they know they can lie about anything. Including the really important stuff. But I’ll quote.

All politicians lie. So many people consider that idea self-evident that I’ve heard it deployed as both a defense of lying and a reason to disengage from our democratic system entirely.

There’s a class of lying so extreme, however, that it exceeds either analytical framework. These aren’t lies about what a politician will do for voters; they’re lies about what the politician had for breakfast, what book he’s reading, whether he played on his college volleyball team. And I’m not talking just about George Santos.

Santos, Eric Adams, and of course Trump. Tucker Carlson used this point as a defense, and won.

An opposition researcher once told me that politicians who hold office at the federal level are invariably a bit delusional. In campaign mode, they’re forced to tell a story about themselves that is idealized and laundered of flaws; eventually they tell that story so many times they begin to believe it. Some slip down the slope into bigger lies.

That’s an unfortunate and all too common arc, but the difference between those people and men like George Santos is that Mr. Santos never even started out with the truth. It’s reasonable to be skeptical of what all politicians say, in the same way that it’s reasonable to be skeptical of promises in advertising or impressions on a first date where both parties are on their best behavior. But the kind of lying we’re talking about here is toxic to the body politic. It fosters not healthy skepticism, but cynicism, and normalizes the idea that dishonesty is just the cost of doing business in politics.

The problem is that some people, apparently, either cannot tell when politicians lie this extremely, or don’t care.

\\

One more about Americans’ view of the economy. Yes, we can blame social media, and those who rely on it.

AlterNet, Carl Gibson, 24 Nov 2023: ‘Not just wrong but dangerous’: How social media is warping Americans’ view of the economy

Since President Joe Biden took office, unemployment has declined and stayed low, real wages are up for low-income workers, inflation is trending downward, consumer spending remains high and disposable income per capita is steadily rising. So why are so many Americans mad about the economy?

According to a new Washington Post report, social media could be playing an outsized role in determining how Americans perceive the strength of the current economy. The Post pointed to a viral 2022 TikTok in which a customer at an Idaho McDonalds posted that he paid over $16 for a limited edition “smoky” double quarter pounder BLT with large fries and a Sprite.

…

In addition to Topher Olive’s TikTok, the platform is full of viral content in which creators incorrectly assert that America is in the midst of a “silent depression.” Another viral TikTok falsely claims that Americans have “the lowest purchasing power we have ever had in American history.” The Post highlighted another post in which a creator wrongly stated that “we currently are making less than at the height of the Great Depression.” The prevalence of viral content souring Americans on the economy now puts Biden administration between a rock and a hard place, as it has to walk a fine line between touting its on-paper economic accomplishments while not dismissing the concerns of struggling working-class Americans.

\\\

LA Times, Kliph Nesteroff, 26 Nov 2023: Opinion: How the culture war demonized comedy and convinced America we’re more polarized than ever

Excerpt from a book by the writer.

The modern news cycle presents us with a new controversy every week. If social media is any indication, comedians, actors, musicians and filmmakers are continually under attack. We are engaged in a battle for the soul of the nation. Free speech is dying. The country is polarized like never before.

These are common beliefs. But do they hold up to scrutiny?

In the old days of newspapers, one could read disturbing articles and horrific headlines — but readers looked at them once and threw them away. Today, with social media, we scroll through the same horrific headlines over and over again, reinforcing a perception of catastrophe. There are awful things happening in America to be sure, but a good deal of what we are exposed to is intentionally composed to incite or manipulate the reader, placing it in the category of “culture war.”

The culture war can be defined by a simplistic philosophy: “We are good. They are evil.” The term “they” is left intentionally vague, a convenient placeholder for whoever needs to be demonized at any given time.

This deliberate corrosion of American culture comes from the right, of course.

The modern culture war was largely crafted by Paul Weyrich, a political strategist who exploited hysteria for political purposes. Weyrich was a lecturer for the John Birch Society’s speaking circuit in the early 1960s. The John Birch Society was founded in 1958 by Junior Mints manufacturer Robert Welch with other businessmen, including Fred C. Koch, father of the Koch brothers. They accused Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. of belonging to a Soviet conspiracy and warned that the Civil Rights Act of 1964 would lead to tyranny.

The writer goes on with examples from popular culture, including comedy. But he claims those common beliefs are false.

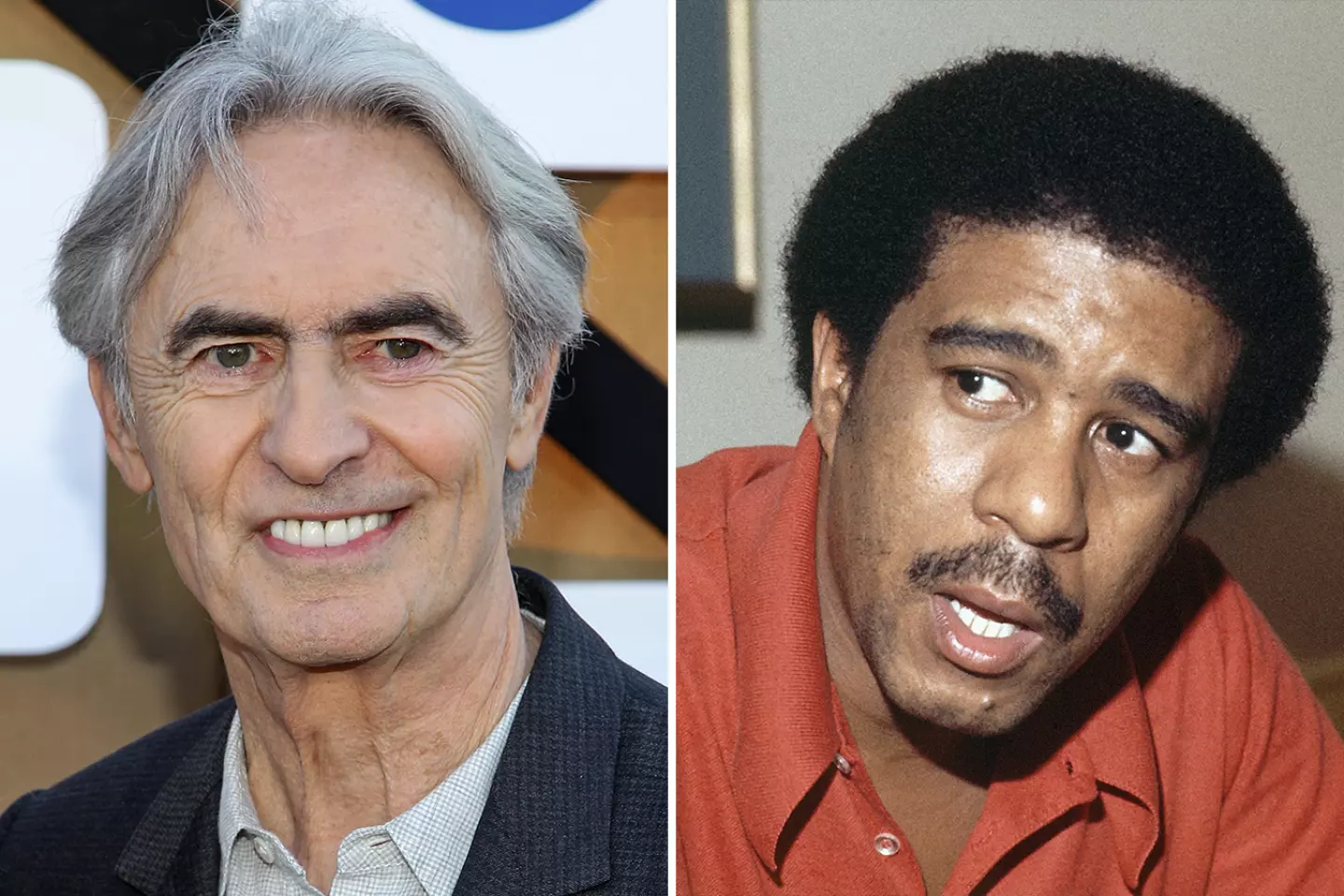

Despite what we are frequently told, comedy in particular has far more freedom of speech today than at any previous time in American history. For most of the 20th century, comedy about politics, religion or sexuality was forbidden, and a comedian who swore onstage risked jail time. As late as 1974, Richard Pryor was arrested for “disorderly conduct” simply for cussing in his stand-up act.

The relentless complaints found on social media are used as evidence that “you can’t joke about anything anymore” — but the same argument existed in the 1950s and ‘60s when most complaints came through the mail.

Good point about how newspapers always got lots of letters of complaint, but would print one in a hundred. Now all those complaints are out there on social media. That doesn’t mean more people are complaining.

But the culture warriors like to feel oppressed. Conclusion:

“There’s no question there’s now more freedom of expression in comedy today,” says Ernest Chambers, an Emmy-winning comedy writer who produced “The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour” for two seasons. “I mean, having been through the Smothers Brothers situation — what we could and could not say 50 years ago compared to now? It’s no comparison. People just don’t know their history.”

That’s precisely the way the advocates of the culture war like it.

\\\

This ties in to the comments I made four days ago about not doing your own research, but rather finding a source you can trust. But who to trust?

NY Times, Jessica Grose (subscriber only newsletter), 25 Nov 2023: Americans Under 30 Don’t Trust Religion — or Anything Else

This piece is part of a series about Americans moving away from religion: Read part one, part two, part three, part four and part five. (I probably have not read all of these.)

He [Ryan Burge, a political scientist at Eastern Illinois University who is a pastor and the author of “The Nones: Where They Came From, Who They Are and Where They Are Going.” (Amz)] thinks the big story here is that so many younger nones categorize themselves as nothing in particular rather than as atheists or agnostics. If you’re an atheist or an agnostic, you have a defined worldview. Whereas with many young Americans, Burge said, “they look at all the religion options and say, ‘I really don’t want to pick a side.’ And that’s what nothing in particular is. It’s not religious, obviously, but it’s also not secular, either. It’s kind of, ‘No, thank you. I’ll pass on the question of religion.’”

And while some of their disaffiliation is driven by the same reasons we’ve seen for older millennials and Gen X, what distinguishes the under-30 set is a marked level of distrust in a variety of major institutions and leaders — not just religious ones. So it makes a certain kind of sense that they don’t want to associate too closely with any defined group.

Religious institutions having high-profile sexual abuse cases were part of the problem. So to:

Several under-30s whom I spoke to said their views on L.G.B.T.Q. acceptance and the role of women in their churches were also factors in their moves away from organized religion.

More commonly:

When I talked to several readers under 30 about moving away from the faith traditions they were brought up in, more than one used the metaphor of a Jenga tower: When they lost faith in the religion they were raised in, it was as if load-bearing blocks were being removed and eventually the entire structure collapsed.

The essay closes:

Even though being a none tends to be culturally accepted among younger Americans, that doesn’t mean that distancing oneself from religion is easy. Kevin Miller, who is 29 and lives in Tennessee, also used the Jenga analogy — after one block fell, it all collapsed pretty easily. But he underscored how painful the experience has been for him: “Especially in my faith journey,” he said, “there’s such a heavy emphasis on, it’s like, you and Jesus. And I really felt like Jesus was my very best friend. And so to move beyond that was losing your closest friend.” Building a fulfilling world back up took him years.

I could comment about how weird the idea of feeling like Jesus is one’s best friend strikes me, that is, I could expand on this, but I won’t.

But the broader point is: what institutions are these people supposed to trust? Are there none? I think there are. They just haven’t noticed them; they’re not particularly well-educated. They’re like fish, unaware of water. But saying ‘they don’t know how good they have it’ — compared to the past, compared to other nations — doesn’t solve anything. How then?

\\\

Listening to this today — Radiohead’s 7th studio album, following Hail to the Thief (which I still think of as its peak), and followed by the two the band has released since.