- Adam Frank on science and the need to account for human experience;

- How “entropy bagels” and other complex structures emerge from simple rules;

- Headlines about the fringe: that North Carolina GOP nominee; how Trump is degenerating; his empty pseudo-religion; his big con.

- And “Don’t Dream It’s Over,” the first Crowded House hit.

The Atlantic, Adam Frank, 5 Mar 2024: The Universe Is Nothing Without Us, subtitled “I was called to science to seek a truth that transcended humanity. What I found instead is much more rewarding.”

I’ve admired the couple Adam Frank books I’ve read (see search for Adam Frank), and I recently even ordered an older book by him that I’ll get to. This essay seems tied to his newest book, The Blind Spot: Why Science Cannot Ignore Human Experience, co-written with Marcelo Gleiser and Evan Thompson.

Now, I’m skeptical of what this article seems to be about, and what the new book seems to be about, and about what Gleiser’s book last year and for that matter Alan Lightman’s book last year seem to be about: a yearning for some kind of humanistic transcendence. Not for God exactly, but for some kind of higher “meaning,” though the history of philosophy and science until now should have taught us that these yearnings turn out to be wishful thinking. Meaning needs to be redefined, as I suggested a couple posts ago.

–But, I’ll read these books, and now this article. Let’s see what it says.

Frank talks of growing up, being attracted by books about the solar system, learning about physics and astronomy. He goes to university. Eventually he comes to doubt the materialist view:

But as my scientific practice deepened, my faith in the perfection of a human-free perspective on the world began to waver. The older I grew, the less satisfied I became with the notion that the beauty I saw in a sunset was just an illusion manufactured by my nerves, which, in turn, were nothing but atoms; the more difficulty I had believing that atoms alone, bouncing around in a void, could describe everything that was real.

His doubts arose while studying quantum mechanics; “the world is inherently fuzzy.” Later, studying phenomenology. Then he met Marcelo…

For a month, we spent endless hours talking in Marcelo’s office, at cafés, and over dinner. We each knew that the orthodox story of science was a mistake. Although it had once made sense, now it was leading to paradoxes and dead ends in fields as varied as physics, biology, and consciousness. We also saw its profound and mostly negative effects on society at large.

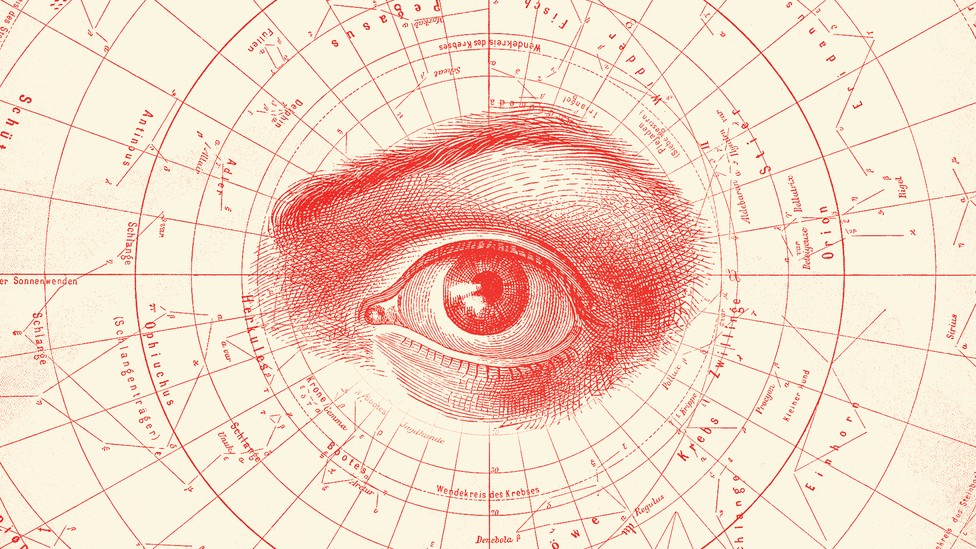

Then, on a rainy walk across campus, we lit upon the central theme. The human eye has a blind spot—an invisible hole in our vision—where the optic nerve connects to the retina. It lies at the heart of our visual field and also makes seeing possible. In the same way, something unseen lies at the heart of science that also makes it work: direct experience.

Unpacking that blind spot took Marcelo, Evan, and me into long jam sessions of big ideas and sharp detail. If we’d met as teenagers, I think we’d have spent energy like that arguing over our favorite bands—or, better yet, formed our own. In the end, that’s kind of what happened. After many years, our work together has led to a new book, The Blind Spot: Why Science Cannot Ignore Human Experience.

Ahhh, beware assigning human motivations to the universe at large. The universe does, in fact, exist independent of human existence. Beware wishful thinking. But I’ll read their books.

\\\

Humans perceive design (and thus god) even when apparent design is the result of simple rules inherent in basic reality — because basic human nature did not evolve to perceive even basic mathematical concepts, which were irrelevant in the ancestral environment.

Quanta Magazine, Jordana Cepelewicz, 27 Feb 2024: ‘Entropy Bagels’ and Other Complex Structures Emerge From Simple Rules, subtitled “Simple rules in simple settings continue to puzzle mathematicians, even as they devise intricate tools to analyze them.”

At the same time, simple rules lead to complex patterns that cannot be simply understood.

Repetition doesn’t always have to be humdrum. In mathematics, it is a powerful force, capable of generating bewildering complexity.

Even after decades of study, mathematicians find themselves unable to answer questions about the repeated execution of very simple rules — the most basic “dynamical systems.” But in trying to do so, they have uncovered deep connections between those rules and other seemingly distant areas of math.

For example, the Mandelbrot set, which I wrote about last month, is a map of how a family of functions — described by the equation f(x) = x2 + c — behaves as the value of c ranges over the so-called complex plane. (Unlike real numbers, which can be placed on a line, complex numbers have two components, which can be plotted on the x- and y-axes of a two-dimensional plane.)

No matter how much you zoom in on the Mandelbrot set, novel patterns always arise, without limit. “It’s completely mind-blowing to me, even now, that this very complex structure emerges from such simple rules,” said Matthew Baker of the Georgia Institute of Technology. “It’s one of the really surprising discoveries of the 20th century.”

The complexity of the Mandelbrot set emerges in part because it is defined in terms of numbers that are themselves, well, complex. But, perhaps surprisingly, that isn’t the whole story. Even when c is a straightforward real number like, say, –3/2, all sorts of strange phenomena can occur. Nobody knows what happens when you repeatedly apply the equation f(x) = x2 – 3/2, using each output as the next input in a process known as iteration. If you start iterating from x = 0 (the “critical point” of a quadratic equation), it’s unclear whether you will produce a sequence that eventually converges toward a repeating cycle of values, or one that continues to endlessly bounce around in a chaotic pattern.

Beware assigning to God anything you personally don’t understand, or find especially amazing. (The Argument from Personal Incredulity.) Yet why would the universe be so mysteriously complex? Because it *is* mysteriously complex, or because it only seems so, given our evolutionary derived minds refined for survival in a very specific kind of environment? There’s likely a way in which the universe couldn’t have been designed/evolved any differently, to exist. As I’ve been discussing.

\\\

Today’s headlines about the fringe.

Slate, Molly Olmstead, 6 Mar 2024: Whew, North Carolina’s Winning GOP Nominee for Governor Sure Has Said Some Things, subtitled “Meet Super Tuesday’s breakout offensive candidate.” Homepage title: “The Next Governor of North Carolina Could Be a Holocaust Denier Who Hates Pretty Much Everybody”

Salon, Amanda Marcotte, 6 Mar 2024: Trump is degenerating before our eyes — MAGA voters don’t notice or don’t care, subtitled “GOP base is now so consumed by incoherent QAnon babble that Trump’s obvious deterioration doesn’t even register”

And two more at Salon:

Salon, Chauncey DeVega, 6 Mar 2024: “They’ve told me he’s Jesus”: Unpacking Trump’s empty pseudo-religion, subtitled “Evangelicals have embraced a ‘despot wrapped in piety’ — and our expert panel says that’s exceptionally dangerous”

Salon, Heather Digby Parton, 6 Mar 2024: Trump’s big con is a flop, subtitled “Trump’s only legislative accomplishment was a massive tax cut for the rich — and the results are now in”

\\\

Still revisiting albums by Crowded House, Neil Finn, the Finn Brothers, et al. This is the song that put Crowded House on the map.

My late friend Larry Kramer worked for Capitol Records at the time — 1988 — and when we drove from LA to Phoenix, for a Westercon, the first sf convention I attended since I’d started writing for Locus, he had a pre-release cassette of the first Crowded House album, which included this song, that we listened to in the car. The order of tracks was different on the cassette than on the later released CD. But this is a song I identify with driving across the California and Arizona deserts, back in 1988, to reach a stifling hot Phoenix. The first time I met Robert Silverberg. And Shayne Bell. And Charles Brown!