- Phil Plait on the scale of the cosmos;

- Beware of pluralistic ignorance;

- How math education can be better taught with examples about money.

Today’s cosmic lesson.

Scientific American, Phil Plait, 8 Mar 2024: The Scale of Space Will Break Your Brain, subtitled “The scale of the cosmos exceeds the bounds of human comprehension. But that doesn’t mean the universe is beyond our understanding” [free link]

Here’s a piece by my favorite pop astronomer (I reviewed one of his books here) about the size of the cosmos. I have a particular fascination for scales of time and space, since they turn out to far exceed anything humans understand intuitively. We resort to exponential notation, and models like Carl Sagan’s Cosmic Calendar. I’ve been collecting such models on this blog when I come across them. What is Plait claiming? What does he mean that this is not “beyond our understanding”?

Plait begins by mentioning the different units that astronomers use, like light-year. Then he starts introducing relative comparisons.

One way to help you grasp this scale is to take it step by step.

The moon is the closest astronomical object to us in the entire universe. On average it’s about 380,000 km from Earth. That’s already a pretty long way; nearly 30 Earths could fit side-by-side over that distance! Or think of it this way: the Apollo astronauts, traveling faster than any human before them, still took three days to reach the moon’s vicinity.

And that’s the closest heavenly body.

The sun is about 400 times farther away from us than the moon is: 150 million km. How far is that? If you could pave a road between Earth and the sun, at highway speeds, it would take you about 170 years to drive there. Better pack a lunch. A commercial jet would be better—it would take a mere 17 years.

When working with objects inside the solar system, it’s convenient to use the Earth-sun distance as a sort of cosmic meter stick. We call it the astronomical unit, or AU, and it’s defined by the International Astronomical Union (the keepers of all astronomical numbers, names and other agreed-upon conventions) to be exactly 149,597,870.7 km. In these terms, Mercury is about 0.4 AU from the sun and Venus about 0.7. Their distances from Earth depend on where all the planets are in their orbit—and increase when respective planets are on opposite sides of the sun—so Venus actually ranges from about 0.3 to 1.7 AU from Earth.

And so on. He considers “the separation between objects in terms of their size.” Alpha Centauri is 30 million “suns” away, and so on. Whereas,

The nearest big galaxy to the Milky Way is Andromeda, which is 2.5 million light years from us. That’s an interesting number because it’s “only” 20 times the size of the Milky Way itself. On the scale of galaxy sizes, galaxies are actually pretty close together.

And so on. He concludes,

After all that, I’ll let you in on a secret: even astronomers can’t truly grasp these scales. We work with them and we can do the math and physics with them, but our ape brain still struggles to comprehend even the distance to the moon—and the universe is 2 million trillion times bigger than that.

So yeah—space is big. And it’s true that we are very, very small. These scales can seem crushing. But I’ll leave you with this: while the cosmos is immense beyond what we can grasp, using math and physics and our brain, we can actually understand it.

And that makes us pretty big, too.

So: he means we can “understand” these distances using math and physics and our brain. Which means, well, a very few of us understand them. (And some people simply deny them.)

\\

And then today’s psychological lesson.

Big Think, Jonny Thomson, 8 Mar 2024: How to spot “pluralistic ignorance” before it derails your team, subtitled “When all your teammates fall for ‘the emperor’s new clothes,’ the results can be disastrous — here’s how to bust the groupthink.”

This goes to my repeated advice: you will not gain understanding of the world from within any kind of crowd. Not a congregation, not a sports stadium, not even in a business meeting. Crowds have different motivations — group solidarity — than acknowledging reality.

Key Takeaways

• “Pluralistic ignorance” occurs when a group of people stay silent or fail to act because they wrongly think everyone else believes differently from them. • It’s the psychological version of “the emperor’s new clothes” and it reveals a fundamental issue in our “theory of mind.” • Here we look at three examples of pluralistic ignorance in the workplace — and how we can beat it.

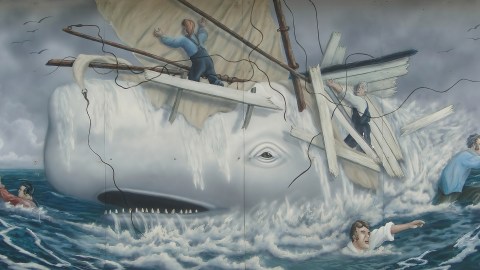

The examples include Captain Ahab in Moby Dick, and a 1950s experiment in which

if you put people in a group who all claimed an answer was wrong, they were almost always more likely to agree with them, even when they thought the answer was different. This still proved true even when the answer was obviously wrong.

The third:

John Darley and Bibb Latané showed a similar effect in the 1970s, when “job applicants” for a fake job would sit in a room increasingly full of smoke and not say anything so long as others didn’t, either.

Ways to avoid this: build a question-friendly environment; beware the social loafer; break patterns of group think.

\\\

And another psychology matter, related to math education.

NY Times, Peter Coy, 4 Mar 2024: The Key to Better Math Education? Explaining Money. [gift link]

In one of the books I recently read, probably Pinker’s, there was a point that human beings are poor at statistics and risk assessment — except in situations when their personal prosperity is at stake. Then our minds are honed for cheater-detection. This item sounds analogous. Coy begins:

I offer to pay you $200 in one year if you give me $190 today. Good deal or bad deal?

It’s the kind of math problem you might encounter in real life, as opposed to, say, whether the cosecant of a 30-degree angle is 1 or 2. You can imagine students perking up and paying attention when they realize that they need to know algebra to avoid being cheated on a loan.

Math and personal finance make a perfect fit. Students grasp concepts such as exponential growth and regression to the mean much better when they see how those subjects apply to their daily financial lives.

It goes on about “a finance-infused high school math curriculum, FiCycle,” with examples.