Items today are follow-ups to items from the past couple days, it turns out.

- Ethan Siegel at Big Think puts that dark matter claim into the perspective of how science works;

- Tom Nichols’ update of The Death of Expertise aligns with yesterday’s piece about America’s decline;

- A new book by Fareed Zakaria attempts to explain the backlash to the liberal revolution of the past three decades.

First of all, a very thorough response to that study that claimed to disprove the idea of dark matter, which I last wrote about here.

Big Think, Ethan Siegel, 22 Mar 2024: Ask Ethan: Has a new study disproven dark matter and dark energy?, subtitled “There are a wide variety of theoretical studies that call our standard model of cosmology into question. Here’s what they really mean.”

Key Takeaways

• Like clockwork, every few weeks a new study comes out claiming to overturn a cosmological cornerstone: there’s no Big Bang, dark matter or dark energy doesn’t exist, the age of the Universe is wrong, etc. • While all of these claims routinely make a splash in the popular media, they hardly ever garner attention among the community of scientists who study these phenomena, and for good reason. • Theorists need room to explore new ideas or resurrect old ideas, even if they’re in severe conflict with what we already know. It’s how theories develop, but let’s not fool ourselves into believing them prematurely.

First of all, Siegel addressed this claim here, last year when it first appeared.

Second, in today’s piece he provides some insight into the workings of scientific research, and the publications of scientific papers, which of course are much more complicated than most people realize. First he establishes what would be needed to overturn any kind of current scientific consensus.

In order to supersede a current line of scientific thinking, or to supplant the leading theory with an alternative, there are generally three hurdles that need to be cleared. They are as follows.

- You must, with your new theory, reproduce all of the pre-existing successes of the old theory.

- You must, as motivation for your new theory, successfully explain something that the prevailing theory either fails to explain or is agnostic about (i.e., has no explanation for).

- And then, as the critical test, your new theory must make novel predictions about a yet-unmeasured phenomenon that differ from the prevailing theory’s predictions, and then you must go out and make those critical measurements.

This is a high bar to clear, and when it comes to alternatives to our consensus picture of the Universe — either from a particle physics or a cosmology standpoint — it’s too restrictive. If we demanded that an alternative theory clear all three of these bars before accepting it for publication in a scientific journal, we would have published no new theory papers in particle physics or cosmology for several decades.

What I’ve never appreciated is how, because of this high bar, scientists are allowed to, essentially, speculate.

Instead, what we allow researchers to do is to consider an alternative idea, explore it, develop it, and consider it as a possibility even if it directly conflicts with already existing data. We allow them to say, “We know this is not reflective of reality, but in the interest of exploring what might someday lead us down a fruitful path, or provide a new avenue along a path previously thought to be closed off completely, we now consider it anew.”

And some scientists hate this. Yet the system allows for it.

The second half of this is about how the scientific press works. Scientists get such speculative papers published in journals, not always peer-reviewed; journals issue press releases; and aggregator websites — like phys.org, the source of the piece I posted about on the 16th — simply pass those press releases as news.

And he concludes, concerning this particular claim, that it leaves many of the observations explained by the standard theory unexplained.

And the piece has a lot of cool charts and graphics.

So file this piece under: interesting, but in no way substantive. Speculative at best. And another lesson in learning how to absorb the news, even scientific news.

\\\

This piece aligns with yesterday’s article. It’s an excerpt from an updated edition of Tom Nichols’ The Death of Expertise, which I reviewed about five years ago here.

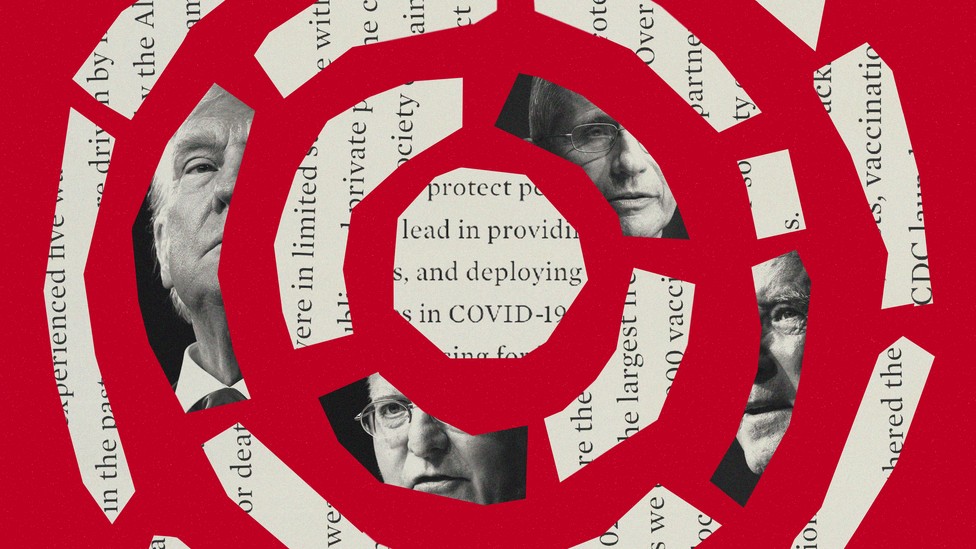

The Atlantic, Tom Nichols, 22 Mar 2024: When Experts Fail, subtitled “They saved us from disaster during the pandemic—but they also made costly errors.”

I’ll quote just the first para of this article.

Experts hate to be wrong. When I first started writing about the public’s hostility toward expertise and established knowledge more than a decade ago, I predicted that any number of crises—including a pandemic—might be the moment that snaps the public back to its senses. I was wrong. I didn’t foresee how some citizens and their leaders would respond to the cycle of advances and setbacks in the scientific process and to the inevitable limitations of human experts.

As I summarized in my review of the original book, “Some would say, experts have been wrong before, so why listen to them now? Because even being wrong on occasion, they are far more often right.” And somehow most people do not understand this.

\\\

One more for today, not unrelated to the previous item.

Washington Post, Fareed Zakaria, 22 Mar 2024: Opinion | How to beat the backlash that threatens the liberal revolution

It opens:

We are living in an age of backlash to three decades of revolutions in different realms. Since the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the world saw the liberalization of markets, the democratization of politics and the explosion of information technology. Each of these trends seemed to reinforce the other, creating a world that was overall more open, dynamic and interconnected. For many Americans, these forces seemed natural and self-sustaining. But they were not. The ideas that spread across the globe during this era of openness were American, or at least Western, ideas, undergirded by U.S. power. Over the past decade, as that power began to be contested, those trends began to reverse. These days, politics around the world is riddled with anxiety, a cultural reaction to years of acceleration.

I’ll note that it’s an excerpt from Zakaria’s new book Age of Revolutions: Progress and Backlash from 1600 to the Present, to be published next Tuesday. I’ll note that I very much liked his previous book, Ten Lessons for a Post-Pandemic World, which I reviewed here. And I’ll note this idea of progress and backlash is exactly what I’m more worried about lately, with Americans’ growing rejection of both science and democracy.

And this applies to science fiction. Is there a limit to collective human intelligence, as the pace of change has increased over the past century? Was science fiction primarily a 20th century phenomenon? Has science fiction’s optimism about the future been misplaced?