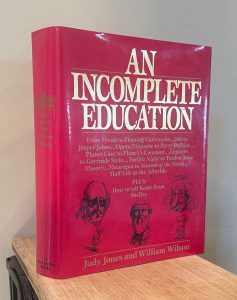

I think I mentioned this book before. It’s a compilation of rough summaries of twelve general topics, from American Studies to World History, with literature, music, philosophy, religion, science, and others in between, written for people who worry that their general education has been lacking in one area or another. As I always have. I bought the book years ago — it’s copyright 1987! It’s one of those books you glance through from time to time. This past February, I read the 36 page section on philosophy, and took notes.

The book doesn’t pretend to be a set of academic overviews; it’s very biased toward the popular ‘greatest hits’ of each subject, i.e. what ordinary people think of when thinking about those subjects. And the tone is a bit wise-acre, even snarky.

The first section identifies the five major areas of philosophy.

- Logic: what’s valid, invalid.

- Ethics: what’s good, right.

- Aesthetics: beauty and art, standard and judgments. Is there a relationship between beauty and goodness?

- Epistemology: how do we know what we know?

- Metaphysics: the big one, the search for ultimate categories of existence, essence, time, space, etc.

I’ve always been most fascinated by the fourth (since, as I’ve noted again and again, so many people, especially conservatives, seem to believe things that are objectively not true), and then the fifth (which is in part what science fiction is about). The section then mentions other ‘ologies,’ like Ontology, the study of being; Eschatology, concerning end states, death, the afterlife, immortality, redemption; Teleology, the idea of purpose in nature; Idealism, and Materialism.

The second section summaries key points about twenty major philosophers, and for each one, identifies best known works, readability, qualities of mind, catchphrases, influence, personal gossip, and current standing. This is where the authors occasionally get snarky. The twenty are: Plato, Aristotle, Saint Augustine, Saint Thomas Aquinas, Niccolo Machiavelli, Rene Descartes, John Locke, Baruch Spinoza, Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz, David Hume, Immanuel Kant, George Friedrich Wilhelm Hegel, Arthur Schopenhauer, Soren Kierkegaard, William James, Friedrich Nietzsche, Henri Bergson, Alfred North Whitehead, Ludwig Wittgenstein, and John Dewey.

(What, Whitehead but not Russell? Don’t understand why. Is it because Russell wrote too many popular books?)

Following sections are about “five famous philosophical mind games”: Zeno’s arrow; Plato’s cave; Burdan’s ass; Occam’s razor; and Pascal’s wager. Then about ‘deduction vs. induction’ and ‘a priori vs. a posteriori’.

And then, what struck me as most interesting, a section, pp330-333, called “What Was Structuralism?” subtitled “And why are we telling you about it now that it’s over?” My notes:

A French intellectual movement that peaked in the 1960s. More of a method. Its principles: components of a system have meaning only in their relations to one another; those relationships are binary; all cultural phenomena are governed by the same principles, and are thus related. They reflect the way the human mind sorts things. Began with linguistics. Levi-Strauss took it up, interpreting primitive cultures and mythologies. Men think in myths, he said. Was an attempt to apply science to areas it had never been applied, though it came to have Marxist overtones, in questioning who has power and why. Roland Barthes could analyze any experience into structuralist terms. Also: Michel Foucault; Jacques Lacan; Umberto Eco (semiotics). Similar: Noam Chomsky, Jean Piaget.

It preceded post structuralism, aka deconstruction. Derrida, and some of the others. About questioning a work along the fault lines of its assumptions. Which leads to questioning authority, a very Eighties survival tactic.

[[ this sounds a tad like consilience, except that dividing everything into binaries seem simplistic ]]

(End notes I took while reading the book.)

I noticed the term in my rereading of E.O. Wilson in March; Wilson dismisses structuralism much as he does other academic trends that he feels are culturally driven and unmoored from reality. Growing up, I was vaguely aware of such trends, like deconstructionism, in which the literal text of a book or story could never be taken at face value; rather, it was about the biases of the writer and his culture, and answered the question, why did the writer write this story and not some other? I still think that’s a valid question, but not in the way they thought. (See my forthcoming essay; it’s not about culture, it’s about the biases of human nature.)

The final section of this chapter about philosophy is about “Three Well-Worn Arguments for the Existence of God.” Where philosophy and cosmology overlap: a lot like wishful thinking. The cosmological argument; the ontological argument; the teleological argument.

These are arguments that will go on until the end of time, or at least the end of the human species. There will always be people who find these arguments persuasive, because of their limited education and experience — relying on base human nature, prioritizing tribal values. (Education is a process that has to start over again for every single individual, and doesn’t necessarily happen.) And those who, given their greater perspectives and understanding about the world, find those arguments childish.