- About a writer I’d never heard of, Tim Urban, and his book, and their connection to Luigi Mangione;

- The psychological motivations of the drone alarmists.

NY Times, David Wallace-Wells, 18 Dec 2024: Can Anyone Make Sense of Luigi Mangione? Maybe His Favorite Writer. (gift link)

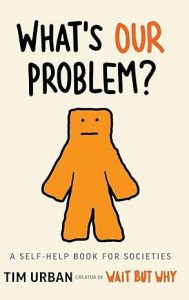

Luigi Mangione of course is the guy implicated in the murder of the UnitedHealthcare CEO in New York City a few weeks ago. So who would his favorite writer be? Ayn Rand? Well probably not. Who then? Tim Urban. Who? According to this interview by Wallace-Wells he’s a “popular blogger, essayist and author of the website Wait but Why and a 2023 book dilating on the problems of uncivil political discourse, called ‘What’s Our Problem?'” And an old friend of the interviewer (whose book on the future of climate change I reviewed here).

Urban doesn’t know why Mangione would have liked his book, and wonders if he misunderstood it. So what it his book about? Urban:

If I had to sum up the essence of my book, it’s a reminder of why liberalism is good — the kind of liberalism that Martin Luther King Jr. was talking about when he said that the founding fathers wrote a promissory note and check bounced. I think of it as a house that we’re all living in. Inside the house you have progressives and conservatives and you have far right and far left, and you have centrists and you have libertarians, and you’ve got all kinds of people and they’re sitting there arguing, but we all agree the house is good. But the house isn’t in perfect condition — this door isn’t working the way it’s supposed to, the heating isn’t working, let’s fix it. And some people argue: That’s not how you fix the house, or it’s working fine, or it’s not working fine for me. This is what’s going on inside the house, and that’s great — that’s liberalism. Fight about the house and over time the house gets better. And then there are movements that I see as outside the house, with wrecking balls. And their movement is, let’s break the house.

And the point of the book isn’t that you should never be mad at the health care industry — it’s that the house’s liberal nonviolent tools have historically been the most effective way to fix things. Granted, I’m sure people who hate the health industry are saying, “Where’s the change? We’ve been trying and it’s still awful.” And that may be true. But when you use political violence, what you’re doing is you’re trying to fix something in the house while smashing through one of the house’s support beams. And if you keep doing that, now someone else will assassinate someone on your side, and before you know it, it’s the road to hell.

And this exchange (between Wallace-Wells and Urban):

But if we’re taking this seriously as an ideological act, one way of explaining it would be that this is someone who has concluded that the house is broken and cannot be fixed from within.

That is a radical position that I don’t agree with and I don’t think history supports. The amazing thing about liberalism is that it enables improvement over time with nonviolent means, and as flawed as it is, the alternative is worse.

\

More revealing is the Amazon page for the book: What’s Our Problem?: A Self-Help Book for Societies. First of all, it’s self-published, by “Wait But Why” (also the name of his blog). Second of all, the 596-page hardcover edition is $57.20, an exorbitant price compared to books from any traditional publisher, though there’s also a cheaper paperback for $37.99. The print editions just came out last month, but the Kindle edition came out in February 2023. And third of all, the Amazon page doesn’t quote any formal reviews, just blurbs by Lex Fridman, Andrew Yang, Elon Musk (?!) and Bari Weiss.

Nevertheless. Especially revealing is opening the “Read sample” function on Amazon. The book blends text with lots of cartoon-diagrams, rather like some of Robert Reich’s books (and web pages). I’m impressed by the ideas he opens with: a diagram showing how small recorded history is compared to all of human history; a chart contrasting the first 999 pages (so to speak) with the last 1000th; and a section contrasting the Primitive Mind with the Higher Mind, with a ladder between the two. It looks very similar to the contrasts I’ve been making between tribal mentality, or morality, and the modern cosmopolitan mentality, and his discussion looks very similar to the points I’ve been making about how the world is now facing problems that cannot be solved by isolated tribes using the tribal (conservative) mindset. Is this the theme of his book? Further pages show various spectra in how people think about things; again, I’ve contrasted conservative black and white thinking with liberal perception of complexity, of shades of gray and even colors. There’s a comparison between “can I believe it” and “must I believe it,” a key point from one of Michael Shermer’s book, IIRC. How to think like an attorney, vs like a zealot; the idea of intellectual cultures.

All of this is just up my alley; perhaps he’s read a lot of the same books I have and arrived at similar conclusions? But while the book apparently includes 100 pages of notes, the Amazon preview doesn’t include them. I wish the book would get some professional reviewer attention, but if it hasn’t by now, it probably won’t. A quick Google search turns up only reviews by other bloggers.

\

There’s also a website, Wait But Why with this post about his writing the book.

Well, I’ll think about it.

\\\

One more about the drones. Like a lot of mysterious phenomena, they say more about human psychology than about reality.

Washington Post, Opinion by Garrett M. Graff, 18 Dec 2024: Panic over mystery drones says more about people than UFOs, subtitled “Life’s great mysteries aren’t solved while taking out the trash or driving along a deserted highway.”

The rising panic over mystery drones swarming the skies of Mid-Atlantic states reminds us that, in the centuries-long hunt to identify UFOs, humans are usually the weakest link.

America has real national security challenges in the new era of unmanned aerial vehicles in warfare. But an invasion of mystery drones over New Jersey isn’t one of them.

As it turns out, just as eyewitnesses often bungle the details of, say, a car accident on the corner, we are notoriously unreliable when it comes to identifying and reporting UFOs. A huge percentage of “sightings” turn out, upon investigation, to be the planet Venus or other surprisingly bright astronomical phenomena; people on the ground regularly misjudge distances in the sky so that even objects miles away are perceived to be close by.

The UFO mistaken-identity problem is a big part of the reason that the military and scientists now refer to such sightings more precisely as UAP, or unidentified anomalous phenomena — a label meant to capture that many sightings might not be “objects” at all but are more likely to be known, or as yet unknown, astronomical and atmospheric phenomena.

With examples of serious investigators who made serious mistakes. And again, about the psychological:

I’ve always been fascinated by the self-centered confidence that underlies so many UFO reports, that people’s first instinct upon spotting a bright, moving light in the night sky is not to assume the obvious — say, a star, meteor, satellite or faraway jetliner — but instead to imagine that, after an alien craft journeyed thousands of light-years across interstellar space to visit Earth, the aliens would pick that moment on a random Tuesday night to reveal themselves to someone on a dark, rural road or in a suburban backyard. Occam’s razor, the useful medieval theory that argues the simplest explanation is usually the best, would tell you that the sound of hoofbeats more likely means horses than zebras.

And this.

Beyond that, our cultural fascination with UFOs stems from the fact that it is a rare area where we can all gaze upon the deepest frontier of knowledge. As an ordinary person, I can’t add much to the already-advanced scientific and mathematical questions of our time: I’m not liable to crack string theory wide open during a weekend barbecue, nor is my tinkering in the garage likely to deliver to humanity the secret to nuclear fusion.

And yet, as the New Jersey drone mystery reminds us, every time any of us looks out the kitchen window, glances into the backyard sky or drives down an empty highway, we can believe we might see that one glowing light that changes everything.