A couple weeks ago I noted, without any kind of deep analysis, a David Brooks essay about his experience of faith, and how it involved random emotional feelings of transcendence and nothing about perceiving the actual nature of reality.

OnlySky, Bruce Ledewitz, 3 Jan 2025: What David Brooks’s search for God can teach secularists, subtitled “Brooks’s essay is the kind that often exasperates nonbelievers. But is there something of value to secular civilization in his God-optional conclusions?”

Does he mean, is there some kind of rhetorical ploy that seculars can use to similarly appeal to peoples’ subjective senses of awe and meaning?

There will never be a secular civilization until we secularists can produce the kind of essay New York Times columnist David Brooks just published about his search for God. The importance of the essay lies not in the content of his journey but in its seriousness and depth. Brooks confronts secularists with the old Kantian question—what can we hope for in life?

My accommodation with this question is that I’m not interested in ways to create a secular civilization. I don’t think it will ever happen. Human nature is unlikely to change anytime soon, and you can’t argue people out of positions they’ve arrived at culturally or emotionally. The best I can do is explore ways that an individual can become wise, and perceive why subjective and supernatural impressions are usually not descriptions of reality. And that reality, if you look closely at it, is much more interesting. Subjective and supernatural impressions only reflect human nature, which has become optimized for survival, not for perception of reality.

Ledewitz summarizes Brooks’s key points.

First, Brooks asserts that the search for God is not, as he had thought, a matter of belief—not about arguments over whether God exists. The search for God is more akin to falling in love. The experiences that lead one to God are “numinous”—”the scattered moments of awe and wonder that wash over most of us unexpectedly from time to time.”

The second lesson is that religion is not made up of such moments. Quoting the poet Christian Wiman, Brooks writes that “Religion is the means of making these moments part of your life rather than merely radical intrusions so foreign and perhaps even fearsome that you can’t even acknowledge their existence afterward.” Religion creates a framework for spirituality as the road to God.

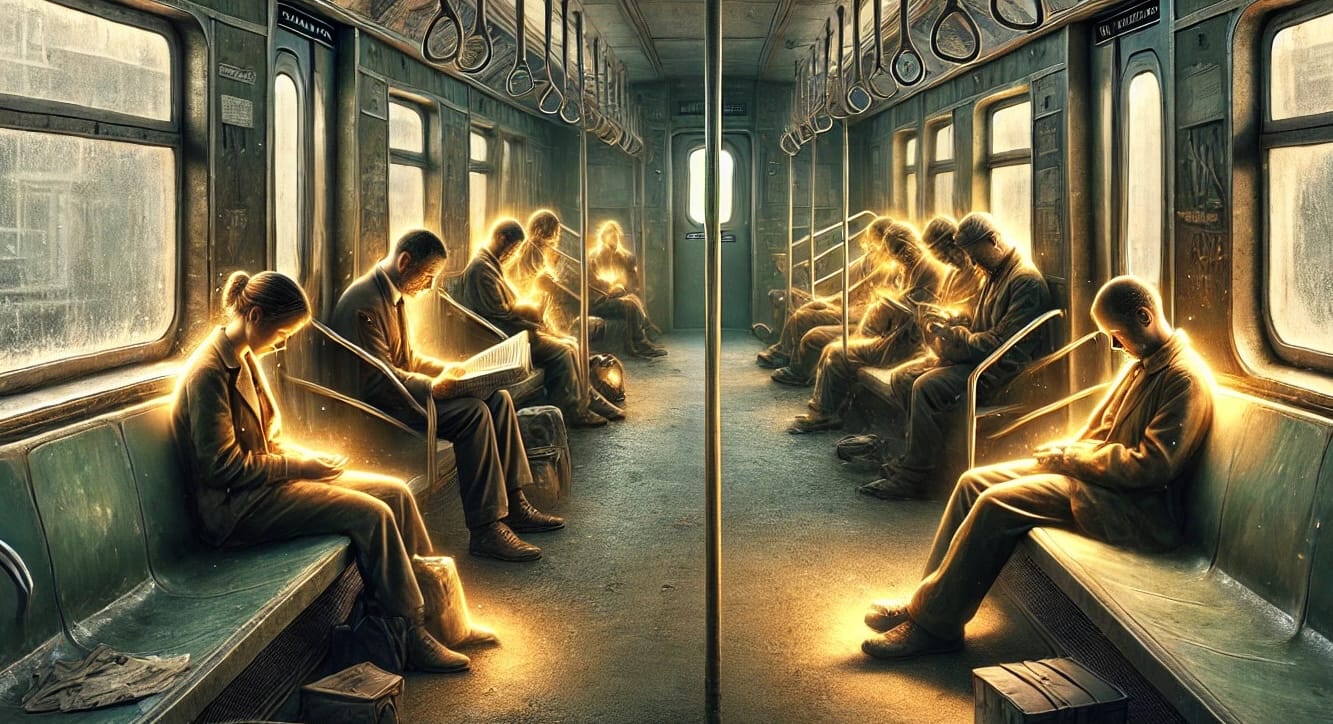

Brooks’ third point is that spiritual experiences can and should change the believer’s consciousness and conduct. These experiences have an ethical component. For Brooks, the sudden realization of his shared humanity with others on a crowded subway car led to his contemplation of the “infinite value” of each person.

Fine, fine, but it doesn’t take *religion* to arrive at these insights. The problem with religion is that various people all around the world might have these insights and think they justify their own particular tribal or cultural mythology — to the point where they need to battle the unbelievers. (See: New Orleans attack.) All it takes to accommodate these insights is a morality that has advanced beyond the tribal to one that acknowledges the humanity of every person in the world. And that certainly hasn’t happened due to religion, as the third point claims.

Ledewitz seems to understand this.

But this unhappiness follows not from the decline of religion, but the failure of secularism to offer anything more than a tired, dispirited and unconvincing materialism in place of religion—a failure to offer a Hallowed Secularism, as I put it in the title of a book years ago. This renewed search for religion is not really about religion as such. It is a search for a universe that is on our side, as the theologian Bernard Lonergan put it—a universe of purpose, goodness and beauty.

And of course we can assign such unhappiness to the various psychological biases like those of narrative and the just-world fallacy. These biases, or beliefs, have helped the species survive, which is their point; they helped people feel better in the ancestral environment, and people are now unsettled by the modern world that seems to challenge those assumptions.

Ledewitz checks in with some writers who are trying to identify a secular world of awe, even transcendence. Which happens to be real.

Clearly, a life enmeshed with awe and wonder is available to the secularist. There is already a well-established phrase for this search—many secularists say they are “spiritual but not religious.” Even a secularist as committed to sober reason as Richard Dawkins wrote a book in 2011 entitled The Magic of Reality. Many of the great scientists and mathematicians in the West have been intoxicated by the beauty of truth.

…

If we secularists value transcendence, if we believe that secular life also can be a grand adventure—beautiful and exciting—even for ordinary people, we need an accessible story of reality that similarly creates a framework for meaning.

A lot of work along this line is going on, from Brian Swimme’s The Universe Story, to Bobby Azarian’s The Romance of Reality, to Nicholas Christakis’s Blueprint. These are fully natural antidotes to reductionist materialism.

Of course a few books will persuade only the few thousand people who happen to read them, and are not already convinced. I continue to think that humanity will remain besotted by religion and the supernatural indefinitely, with only a minority — a minority that has always existed, despite more or less suppression by religious and authoritarian states — able to find the freedom to understand and explore reality. This minority has brought about our modern world.

Ledewitz concludes:

Is there any way to link our secular path and Brooks’s religious one? The answer is most certainly yes. Brooks goes wrong in thinking he is looking for a kind of person who is God and therefore behaves like a person. That error is the source of the simplistic notion of the wonder-working God. Many theologians have argued that Brooks’s search for this kind of God is a form of idolatry.

But if that understanding of the personal God is abandoned, there is a lot, almost all, of Brooks’s essay that a secularist can accept and learn from. The issue concerns fundamental ontology—what is real. If the universe really is a kind of mysterious goodness, and we receive intimations of that goodness in spiritual experiences, that is a great story. It is a natural story and a reasoned story. It does not require any surrender of scientific discovery. It is in fact good news. It can be our secular gospel.

\\\

Believers like to imagine there is a “god-shaped hole” in the brain, which of course should be filled by their own conception of god. Jerry Coyne on Richard Dawkins on this subject.

Jerry Coyne, 3 Jan 2025: Dawkins in the Spectator on that pesky “God-shaped hole”

I’ve posted several times on the claim that humans have an innate longing for God that must be filled by either religion or some simulacrum of religion. This is the famous “God-shaped hole” in our psyche claimed by believers and those whom Dan Dennett called “believers in belief.” This trope appears regularly, and the last time I discussed the “God-shaped hole” was on Christmas Eve when a Free Press article described an atheist mother lamenting the absence of religious traditions to which she could expose her children on Christmas.

With the recent kerFFRFle in which some people (including me) argue that wokeness and gender activism have taken the form of a quasi-religion—a claim that’s the subject of a whole book by John McWhorter—some people have taken to blaming atheists for creating this hole and for the need for something to replace traditional faiths. By taking away people’s religion, they say, we have made society worse as erstwhile believers start glomming onto all kinds of nonsense. (Apparently religion is a good form of nonsense.)

Actually, the premise of Nicholas Humphrey’s Leaps of Faith — another book I read years ago and should catch up with here on this blog — is that the diminution of religious faith, in the face of the Enlightenment and the scientific revolution, has led to consolation from supernatural beliefs, and increased credence in any number of fanciful conspiracy theories.

Believers of course use this “god-shaped hole” to justify the existence of their own god. Here’s my take on that reasoning: Perhaps what people don’t understand is that they have a science fiction shaped hole. If only their tastes were the same as mine, and they read more science fiction, the world would be a better place.