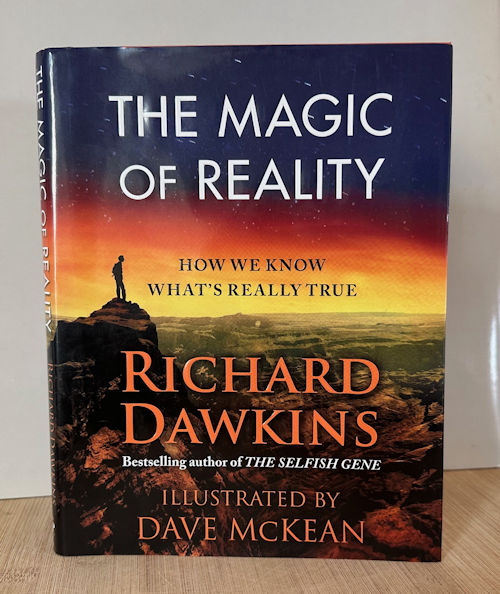

Subtitled: How We Know What’s Really True

Illustrated by Dave McKean

(Free Press, Oct. 2011, 271pp, including 6p of index and acknowledgements)

When I was organizing my nonfiction books notes and posts last December, I was surprised that I had nothing on this book, though I was sure I read it. My records show I read it shortly after publication, in 2011. I suppose the reason I didn’t write up any notes is that it’s Dawkins-lite, somewhat like FLIGHTS OF FANCY (review here), heavily illustrated and aimed at, perhaps, younger readers. The themes are pretty basic. Still, those themes are also fundamental. So I reread the book last month, to capture the book’s ideas here. There are three essential ideas.

The first essential idea is in the subtitle. The book is a tour of a several basic scientific topics, not just to provide the current state of knowledge on those topics, but to explain *how* people reached these conclusions. You don’t get that in intro science courses in high school or even college, unless you specifically take history of science courses. (At least, in my experience.) Thus some people are put off by what they see as the impudence or even arrogance of scientists dictating what’s true and what’s not — especially when what they claim to be true conflicts with religious myths.

The second essential idea is that there have always been myths about what people have imagined to be true. Almost every chapter begins with examples of myths from various cultures, about each topic: what the sun is; who the first person was; what a rainbow is; and so on. This is what struck me when I first read the book, especially how Dawkins casually mixes the very popular myths (those of “the Hebrew tribes of the Middle East [with their] single god, whom they regarded as superior to the gods of rival tribes” for example) alongside mostly forgotten myths from other cultures (in this case, myths from the Tasmanian aborigines, and from the Norse people of Viking seafarers). There’s some speculation as to why those cultures might have imagined their particular myths, though in most cases nothing is obvious; and Dawkins pauses to wonder to what degree those myths contain any truth at all, by modern standards. (Answer: not much.)

The third, most essential idea is that reality is much more interesting, and more magical in a poetic sense, than all those myths.

The book is replete with illustrations, of both the myths and of the historic scientific developments, all by Dave McKean, who is famous among other things as a science fiction artist, having done cover for many SF books. (Here’s a bibliography.)

1, The first chapter spells out what reality is, and what magic is. Reality is everything that exists, including things we don’t perceive directly but can deduce exist or must have existed. We use ‘models’ [theories] to figure out what might exist; then we go looking for evidence. Science is about explanation; its enemy is the supernatural, which explains nothing. There are three kinds of magic: supernatural, stage, and poetic. The first is found in myths and stories; the second consists of tricks done on a stage, either honestly (e.g. Penn and Teller) or by charlatans claiming psychic powers; and the third is the feeling that comes from beautiful music or a sky full of stars, things moving or exhilarating. The facts of the world are magical in that sense.

A key principle throughout is the slow magic of evolution, which we didn’t understand until the 19th century. How things change gradually, a bit at a time, over generations.

The next nine chapters address individual topics. I’ll briefly summarize each one.

2, Who Was the First Person? This is where Dawkins reviews the myths of the Tasmanians, the Hebrews, and the Norse. The reality is: There wasn’t one. Every person had two parents, and they were people too. But not forever. Dawkins imagines a stack of photographs of all your grandfathers, where some 50,000 generations back they would be Homo erectus. But there’s never any pair anywhere in the stack that marks the shift from erectus to sapiens. That’s the tapestry of life.

3, Why are there so many different kinds of animals?. Evolution. Populations of animals shift over time (especially when separated by topographical features), just as languages do; when people can no longer understand one another, we call their languages separate. Same for species and when separate groups of a species become disinclined to mate.

4, What are things made of? From the four elements of the ancients — air, water, fire, and earth — to the idea and discovery of atoms, the states of matter, how each element has a different number of protons.

5, Why do we have night and day, winter and summer? History is replete with myths about these. Reality involves the discovery that the Earth rotates, giving only the illusion that the sun goes around it; that the Earth revolves around the sun at an angle from the axis on which the Earth rotates; how summer and winter are reversed in the northern and southern hemispheres. [[ This, I would guess, is something most modern people still do not understand. ]]

6, What is the sun? Lots of myths here too. Sun and moon, man and woman, or brother and sister; a chariot driven across the sky. Actually, the sun is a star. Dawkins provides the usual distance comparisons, and examples of how some other stars are much, much larger than our own, or smaller. The sun’s energy drives life on Earth.

7, What is a rainbow? More myths, more than one connecting a rainbow to a big flood. But of course the rainbow is an effect of sunlight through water droplets; you can never stand at the end; and the sun actually includes many ‘colors’ or wavelengths of light that our eyes cannot see. Humans see only a tiny band in the middle of a huge spectrum. [[ And it’s not a coincidence that we see the brightest bands in that spectrum… it’s adaption. ]]

8, When and how did everything begin? All myths assume the existence of some kind of living creature before the universe itself came into being; oddly, none explain where that creator came from. In reality, there were two leading ‘models’ of the universe until the mid-20th century, when evidence came down on the side of the ‘big bang’ model (as opposed to the ‘steady-state’ model). That came through a chain of deductions: the distance to nearby stars by parallax, to farther stars by ‘standard candles’, how prisms and spectroscopes revealed black lines in spectra which in turn revealed the elements in those stars, how Doppler shifts in those lines revealed that all the galaxies are moving away from one another. Extrapolate back into time: the big bang.

9, Are we alone? Myths about life elsewhere in the universe are all modern: alien abductions and so on. Answer: we don’t yet know, but probably yes. We can make informed guesses, from the number of stars, the number of planets, the likelihood any given planet can support life, and so on.

10, What is an earthquake? Many myths about those. The reality is that there are tectonic plates, and the shapes of the continents have changed over 100 million years. And when the edges of those plates slip against each other, that’s an earthquake. The original idea was ridiculed, being so counter-intuitive (that huge land masses moved), but the evidence eventually won out.

The last two chapters aren’t about particular scientific knowledge, but are a primer about critical thinking, chance and probability, and human nature.

11, Why do bad things happen? In fiction, and myths, there is a kind of natural justice, that doesn’t exist in reality. Quakes and diseases aren’t caused by sin, or evil gods. Instead we should wonder: why does *anything* happen? Bad things need explaining only if they’re more common than they ‘should’ be. We often think they do — e.g. Murphy’s Law — but this is due to a bias of human nature: we’re more sensitive to potential threats than other events. All things happen because of luck, chance, and cause. When people say ‘everything happens for a reason’ they usually imply a reason like sin. But this is leftover from childhood notions of things happening for some reason. Similarly ideas of good and bad luck arise from a misunderstanding of the law of averages.

So the universe doesn’t care what we want. Things just happen. Still, if you’re alive, there may be many things out to get you. Animals, or viruses. Natural selection requires it. Both sides work to survive. And so it pays for wild animals to be paranoid, e.g. that a rustle in the grass might be a predator. This attitude explains many human superstitions. When it goes too far, we say they are paranoid.

Dawkins wonders if illness and evolution are part of a work in progress. And ponders parasites, the immune system, vaccines, how an overactive immune system can lead to allergies and auto-immune diseases. Which perhaps are byproducts of an evolutionary war against cancer.

12, What is a miracle? Nowadays nobody believes in fairy-tale magic, and we understand that stage magic is trickery. But some people do believe in supernatural events that they call ‘miracles.’ Someone you dreamed about dies the next morning. Jesus turning water into wine. Mohamed flying to heaven on a winged horse.

These are due to rumor, coincidence, and snow-balling stories. We usually hear such stories after being passed from person to person. Humans are pre-programmed to see faces of other humans, and this errs in seeing faces everywhere. [[ In clouds, in tortillas. ]] We like creepy stories and don’t bother with evidence. Miracle stories get written down and become hard to challenge, especially in books that are old. They become tradition. Stories like those dreams are simply coincidences. We only tell such stories when they happen, not all the times the person you dreamt about *didn’t* die the next morning. And stories grow in the telling.

A good way to think about miracles comes from David Hume, who said that miracles would be transgressions of the laws of nature. He said, you shouldn’t believe a miracle unless its falsehood would be even more miraculous. An example of a claimed miracle was about two English cousins who took photos of ‘fairies’ in their garden. [[ Arthur Conan Doyle, Sherlock Holmes author, fell for them. ]] Some incidents can harm people, e.g. the panic about witches in Salem, driven by girls making up stories. A famous one was in 1917 at Fatima in Portugal, when two girls claimed to have seen the Virgin Mary, later drawing huge crowds, and a ‘miracle’ involving the sun falling from the sky, supposedly seen by 70,000 people. Consider three options, p257: the sun really did move; nothing moved and the 70,00 experienced an hallucination; or or nothing happened at all, and whole incident was misreported, exaggerated, or simply made up. If the sun had really moved, millions of people over the hemisphere would have seen it. Not to mention destroying the earth. And the crowd had been told to stare at the sun.

People invent stories all the time. And we know that lots of fiction has been made up about this Jesus. Such as the Cherry Tree Carol. [[ I had never heard of this one; an English ballad is based on it. ]] Everyone agrees it’s fiction. It was made up only 500 years ago. We can conclude similarly about all so-called miracles.

Finally. There remain many things scientists cannot explain. But that doesn’t mean that they won’t, eventually. Technology from one generation would have seemed like magic a generation before — Clarke’s third law. Something seemingly supernatural only means we need to improve our science, not give up and call it a miracle.

Truth has a magic of its own. The magic of reality.

\\

To summarize: This is a basic sort of book, not one you’ll necessarily learn something from, if you’ve read other books, and gone to college. But it’s an excellent summary of how we know things that we know, and how ideas of the supernatural can be dismissed. This is a book I would give to a smart 15-year-old.