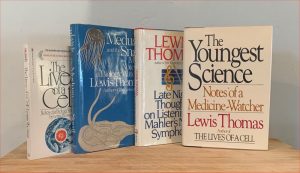

Subtitled “Notes of a Medicine-Watcher,” this is a 1983 collection of essays in an autobiographical structure by the author of three acclaimed books of essays, beginning with THE LIVES OF A CELL. (I reviewed the third one here).

Subtitled “Notes of a Medicine-Watcher,” this is a 1983 collection of essays in an autobiographical structure by the author of three acclaimed books of essays, beginning with THE LIVES OF A CELL. (I reviewed the third one here).

The startling take-away from this book is how little actual medicine there was a century or so ago. That’s what’s alluded to in the title. The essays follow the author’s childhood, his father a doctor working out of their home, followed by stages of his career, with focuses on “1911 Medicine” and “1933 Medicine.” In the early decades of the 20th century, most diseases were simply untreatable. A couple key passages.

Page 27, recounting his own education in 1933:

…the purpose of the curriculum was, if anything, even more conservative than thirty years earlier. It was to teach the recognition of disease entities, their classification, their signs, symptoms, and laboratory manifestations, and how to make an accurate diagnosis. The treatment of the disease was the most minor part of the curriculum, almost left out altogether. There was, to be sure, a course in pharmacology in the second year, mostly concerned with the mode of action of a handful of everyday drugs: aspirin, morphine, various cathartics, bromides, barbiturates, digitalis, a few others….

He was an intern in a hospital, where patients were kept in open wards, with rows of beds along each side of a large room all in view of the ward nurse.

The greatest part of the work done on these wards was simply custodial. Patients came in with their illnesses, almost all of them severe; you did not go to the emergency room for admission to the Boston City Hospital unless you felt in danger for your life. Once you were admitted, transported on wheeled litters through the tunnels of the hospital, up the elevators, and onto the wards, it became a matter of waiting for the illness to finish itself one way or the other. If being in a hospital bed made a different, it was mostly the different produced by warmth, shelter, and food, and attentive, friendly care, and the matchless skill of the nurses in providing these things. Whether you survived or not depend on the natural history of the disease itself. Medicine made little no difference.

And this continued to the 1950s, with the widespread use of penicillin and vaccines.

Other interesting ideas:

p.51, author compares the evolution of language to biological evolution.

p.83: “In real life, research is dependent on the human capacity for making predictions that are wrong, and on the even more human gift for bouncing back to try again. This is the way the work goes. The predictions, especially the really important ones that turn out, from time to time, to be correct, are pure guesses. Error is the mode.”

p.91: How he spends the war on Guam and in Okinawa.

p149: An interesting idea, from Oliver Wendell Holmes: “the key to longevity was to have a chronic incurable disease and take good care of it.” This is because such people are more careful with their care than people who have no such worries, and so are likely to avoid risky behaviors.

p195: How Hubert Humphrey was a patient at the cancer center where author then worked.

p204: About how heart and kidney transplant patients are subject to cancer: 10% within the first year; 50% by 10 years.

p206: “One of the splendid features of the scientific enterprise has always been the urgency with which the participants have insisted on displaying the results of their work as soon as it is completed. With very few exceptions [involving commercial secrets] there are no kept secrets in research.”

p220: He describes his own illnesses and hospital stays.

p235: He listens to Beethoven’s quartets, late at night, at high volume.

p236: How author believes that childhood lasts longer in males than in females.

p239: How he wasn’t paid for the essays that became his three earlier books–but he was given a page for each short essay to write about anything he liked, with no editorial veto.

And ending the book, p247-8, a perspective from 1983:

I am not so optimistic about us. Human beings are getting themselves, and the rest of the world, into deeper and deeper trouble, and I would not lay heavy odds on our survival unless we begin maturing soon. Up to now, we have been living through the equivalent of an early childhood for our species. …Thermonuclear war is the worst case to contemplate [but we have other threats:] overpopulation and crash, deforestation and crash, pollution and crash. With luck we may come through. The luck will have to be incalculable, and unbelievably on our side over the next few decades. The good thought I have about this is that we are, to begin with, the most improbable of all the earth’s creatures, and maybe it is not beyond hope that we are also endowed with improbably luck.