No one would have believed in the last years of the nineteenth century that this world was being watched keenly and closely by intelligences greater than man’s and yet as mortal as his own; that as men busied themselves about their various concerns they were scrutinised and studied, perhaps almost as narrowly as a man with a microscope might scrutinise the transient creatures that swarm and multiply in a drop of water.

… Yet across the gulf of space, minds that are to our minds as ours are to those of the beasts that perish, intellects vast and cool and unsympathetic, regarded this earth with envious eyes, and slowly and surely drew their plans against us. And early in the twentieth century came the great disillusionment.

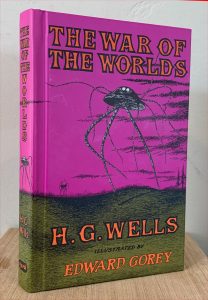

This is one of the most famous of all science fiction novels, of course, and the template for countless alien invasion stories that were to follow. (I noticed how Wyndham’s THE DAY OF THE TRIFFIDS seems modeled on this.) It was the fourth of Wells’ early and most enduring novels. And it’s a novel whose film adaptations — in 1953 and 2005 — tend to dominate the memory over that of the book, as so many films made from books do. So, in prep for writing descriptions for the sfadb novel ranking list, I reread the novel again this past week, taking note particularly of differences between book and films.

- The novel is set in and around London, while the 1953 film is famously set in LA. In fact the novel is replete with locations of towns and villages and rivers in Southern England. It was first published in Pearson’s Magazine in 1897 before the book edition appeared in 1898. The detail was presumably meant to appeal to the local audience.

- The unnamed narrator visits an astronomer friend, and they see through a telescope puffs of incandescent gas erupting from Mars.

- “Falling stars” are then seen near towns southwest of London, including Woking, where the narrator lives. Upon investigation, people find large cylinders, 30 yards in diameter. Their lids screw open, and gray bulks with tentacles emerge. Then heat-rays from the cylinders wipe out nearby observers, and on the next day, Saturday, towns are attacked. A second and third falling star is seen.

- Narrator and his wife flee their home to a cousin in Leatherhead. Huge tripods are seen striding over the countryside, with ropy tentacles hanging beneath. Towns are destroyed; soldiers are killed. Narrator falls in with a curate, who moans about events.

“What does it mean?” he said. “What do these things mean?”

I stared at him and made no answer.

He extended a thin white hand and spoke in almost a complaining tone.

“Why are these things permitted? What sins have we done? The morning service was over, I was walking through the roads to clear my brain for the afternoon, and then—fire, earthquake, death! As if it were Sodom and Gomorrah! All our work undone, all the work—— What are these Martians?”

“What are we?” I answered, clearing my throat.

He gripped his knees and turned to look at me again. For half a minute, perhaps, he stared silently.

“I was walking through the roads to clear my brain,” he said. “And suddenly—fire, earthquake, death!”

He relapsed into silence, with his chin now sunken almost to his knees.

Presently he began waving his hand.

“All the work—all the Sunday schools—What have we done—what has Weybridge done? Everything gone—everything destroyed. The church! We rebuilt it only three years ago. Gone! Swept out of existence! Why?”

Another pause, and he broke out again like one demented.

“The smoke of her burning goeth up for ever and ever!” he shouted.

A bit later the narrator fires back:

“Be a man!” said I. “You are scared out of your wits! What good is religion if it collapses under calamity? Think of what earthquakes and floods, wars and volcanoes, have done before to men! Did you think God had exempted Weybridge? He is not an insurance agent.”

- The narrator’s account breaks to give his brother’s of what has been happening in London: haphazard news, disruption of trains, sense of panic, the beginning of an exodus on foot north by six million people.

- The brother falls in with two ladies in a carriage, heading north then east, to coast, and witnessing an ironclad ram called “Thunder Child” attacking two of the tripods, destroying them but also itself.

- The second part of the novel closes in on the narrator, as he worries about his wife, and holes up with the curate in a wrecked house where another cylinder has landed. As in the films, there is an extended sequence as the people hiding in the house watch as a Martian extrudes its tentacle into the wreckage, probing… Days pass; the curate goes slowly insane and succumbs.

- Narrator eventually emerges and makes his way to London, which seems deserted, except for bodies and lots of black powder. And he realizes the Martians are dead, slain by bacteria, “the humblest things that God, in his wisdom, has put upon this earth.”

- He makes his way back to Woking, where his wife and cousin await him.

- Finally he speculates about the possibility of another attack, and what the future of mankind, and of the Martians, may be.

\\

Points about the book (that are different from the films).

- The Martian ‘ships’ are tripods, i.e. hoods walking on three legs, with tentacles dangling beneath to pick things up (not floating semi-winged things with stalks holding tripart ‘eyes’, as in the 1953 film, as cool as those looked).

- The Martians themselves are huge heads with tentacle-like ‘hands,’ but with no digestive system. In fact they inject blood directly from other living creatures, and they prefer humans, their own sources on Mars having run out. And later studies reveal (this is all in Chapter 2 of Book Two) that they don’t sleep, have sex, ever get sick, wear no clothes, and don’t use wheels. And are perhaps telepathic. (I don’t remember the intent of the invaders to *consume* people being in the films…)

- Explicit in the book is the natural selection angle of Martians succumbing to bacteria that humans had evolved to resist.

Quotes:

- Ch. 3: “Few of the common people in England had anything but the vaguest astronomical ideas in those days.”

- One of the carriage ladies has never been out of England: “She seemed, poor woman, to imagine that the French and the Martians might prove very similar.”

- Near the end: “The broadening of men’s views that has resulted can scarcely be exaggerated. Before the cylinder fell there was a general persuasion that through all the deep of space no life existed beyond the petty surface of our minute sphere. Now we see further. If the Martians can reach Venus, there is no reason to suppose that the thing is impossible for men, and when the slow cooling of the sun makes this earth uninhabitable, as at last it must do, it may be that the thread of life that has begun here will have streamed out and caught our sister planet within its toils.”

- And finally: “I must confess the stress and danger of the time have left an abiding sense of doubt and insecurity in my mind.” He observes how daily life has resumed in so many ways.

I go to London and see the busy multitudes in Fleet Street and the Strand, and it comes across my mind that they are but the ghosts of the past, haunting the streets that I have seen silent and wretched, going to and fro, phantasms in a dead city, the mockery of life in a galvanised body. And strange, too, it is to stand on Primrose Hill, as I did but a day before writing this last chapter, to see the great province of houses, dim and blue through the haze of the smoke and mist, vanishing at last into the vague lower sky, to see the people walking to and fro among the flower beds on the hill, to see the sight-seers about the Martian machine that stands there still, to hear the tumult of playing children, and to recall the time when I saw it all bright and clear-cut, hard and silent, under the dawn of that last great day. . . .

And strangest of all is it to hold my wife’s hand again, and to think that I have counted her, and that she has counted me, among the dead.

The entire text of the novel is here.