This week’s novella covered by the Facebook Group reading Gardner Dozois’s big anthology first discussed here is “Beggars in Spain” by Nancy Kress, first published in the April 1991 issue of Asimov’s Science Fiction.

It won both the Hugo and Nebula for best novella, placed 2nd in that year’s Locus Poll/Awards (to a story by Kristine Kathryn Rusch), and won three lesser awards/polls. It was the basis for a novel of the same name, published in 1993, that in turn formed the basis for a trilogy with later novels Beggars and Choosers (1994) and Beggars Ride (1996).

Kress began writing in the late 1970s, produced three fantasy novels in the early 1980s (which I’ve never read), then settled into writing science fiction, increasingly with a bent toward hard SF of a biotechnical sort, considering issues ranging from genetic engineering to alien psychology. She received award nominations (and one win) for three or four stories in the ’80s, with the one under discussion here, “Beggars in Spain,” won both the Hugo and Nebula and remains her most famous story. Her first big hit.

It’s one of the greatest science fiction novellas of all time.

\

The premise is that a genetic modification has been developed that will allow humans to live without sleeping. The story begins as this treatment is still confidential, but a well-off couple has learned of it and wants the modification for their upcoming daughter.

There are three or four plot-lines, and themes, going on. Dramatically, the couple obtains the treatment and becomes pregnant — but with twins. Of their two baby girls, only one is modified, the other ordinary. This sets up tensions as the girls grow up. The parents split, father taking the modified girl, Leisha, mother keeping Alice. More dramatic tensions.

A second theme is what happens as the sleepless grow to adulthood and live adult lives. Without needing sleep, are they more productive, more successful? The premise of the story is — yes.

This transitions to a third theme, which is how the Sleepless are treated by the rest of society. As the number of Sleepless grows, and are more obviously successful, they become resented and pilloried by society at large, even attacked and driven from their professional positions, and finally (spoiler) into a kind of exile. (It’s even discovered the treatment extends their lifespans — a premise that doesn’t seem entirely necessary, except perhaps for future plotting purposes — and that just makes the resentment worse.)

And a fourth theme emerges from the others, beginning with the philosophical position (of which the father is a follower, it’s mentioned early on) called Yagaiism, after Yagai, the inventor of a generator which powers the world, who has become a popular philosopher, emphasizing personal achievement and how contracts run the world.

As the increasingly oppressed Sleepless contemplate withdrawing from society entirely, they debate the responsibility they might owe society, bouncing Yagaiism off pragmatism, even survival. The key hypothetical is what a passer-by would owe a beggar on a street in Spain. What does a beggar have to trade (in Yagai’s terms, what good is he)? If nothing, if you help him, why? So what do the Sleepless — with their genuine talents and achievements — owe to a society that oppresses them?

It’s this rare balance of human drama, sfnal extrapolation of a new discovery, and philosophical implications of the consequences of that discovery, that makes this story impressive in every way.

\

I read the full novel and its first sequel back when first published, 30 years ago, but don’t retain close memories. It’s been 30 years! But my notes emphasize how the novels settle onto theme of haves vs. have-nots. Intelligentsia as opposed to the willfully ignorant. A theme that never gets tired.

\

Kress is under-appreciated, I think, as a writer of hard science fiction, perhaps because she doesn’t write about physics or starships, and perhaps because her stories are so infused with strong characterizations and complex interpersonal relationships that they don’t resemble the sometimes dry, technical writing of the more nerdish hard SF guys (guys). Kress perhaps occupies a unique position in SF as a writer of characters, and a writer who can extrapolate from actual science.

\

I reviewed several Kress stories during the decade I wrote reviews for Locus, and I’ll quote a couple of those reviews here. The most notable is the novella “Dancing on Air” (Asimov’s July 1993), for its resemblance to “Beggars in Spain.” From the June ’93 Locus:

The July Asimov’s features Nancy Kress’s “Dancing on Air”, a full-bodied novella with similarities to 1991’s “Beggars in Spain”. Another biological development is sweeping society. Here it’s nano-tech bioenhancement, which can create a guard dog that talks, or ballet dancers who can perform hitherto impossible feats. The ballet world is the focus of the story, with the American scene puritanically resisting the bioenhancement movement that has been embraced by European dancers. But two American dancers have recently been murdered, and both were bio-enhanced after all. This attracts the attention of a reporter from an online New York news service whose own daughter is an aspiring dancer. Kress plays the themes on all these levels brilliantly, though not flawlessly — the initial murder mystery, for instance, was just a ploy, its solution mentioned in passing and then forgotten. But the story excels in many ways: in the tense relationship between mother and daughter; in the authoritative depiction of the ballet world; in the technical plausibility of the biotechnology and its impact on society.

(One might notice a quirk of the Locus house-style here: punctuation goes outside quote-marks unless actually part of the story title.)

\

A later story that I reviewed for Locus was “Flowers of Aulit Prison” (Asimov’s Oct/Nov 1996), winner of both a Nebula and a Sturgeon.

The new stories in the issue include Nancy Kress’s “The Flowers of Aulit Prison”, one of two stories this month set among an alien species and involving a human being as a secondary character. Uli Pek Bengarin, a member of the people of World, is in atonement for having killed her sister; she has been declared unreal for having violated the shared reality of her people. She’s given a chance for repentance by serving as an “informer” at a prison holding others who are unreal, including a Terran who has killed a World child. (Actually, the people of World suspect that all aliens are unreal, so disordered is their thinking.) Uli engages in debate with the Terran, who tries to explain his point of view, and why children were involved in his experiments with memory. After she leaves the prison and makes her report, Uli is left troubled and unsure of her own status. She goes searching for the Terran’s contacts, anxious to learn if she is really a murderer at all.

The story moves from a depiction of a weird alien society to the familiar Kress territory of biomedical SF. Struggling with broken Terran words (“skits-oh-free-nia”) Uli learns that her people’s brain chemistry is partially the basis their conception of reality, and might even be a handicap relative to the Terrans. That’s all very interesting, but I would have liked to see more about how this society functions on an everyday basis. There are some fascinating suggestions, such as the discussion of why baby-stealing isn’t much a crime among the people. But the focus is on Uli and her crisis of conscience, and it makes for a powerful story, even if the larger premise feels inadequately explored.

\

A story I reread a couple years ago (but not this past week) was Kress’ first award-winner, published in 1985, winner of a Nebula the next year. A short story.

“Out of All Them Bright Stars” (F&SF March 1985)

The story is set in a rural diner nearing closing time when one of *them* walks in — one of the blue-skinned aliens who have come to Earth, for unknown reasons, their ship now in orbit. Now here’s one all by itself. The story is all about the reactions of the humans in the diner: the waitress Sally, who treats it politely; the assistant Kathy, who freezes in alarm; the owner Charlie who bursts out of the back room, angrily ordering Sally to get rid of it, using racial epithets. Until government men show up to take the alien away. Sally is left with two things: wondering why the alien came here, to this particular place, what the aliens are up to. And with the troublesome revelations about the characters of her co-workers.

It’s a subtle story, all about the variety of human reactions to the unknown, to the other. But not a revelatory one. We knew this.

\

Finally, three Kress stories I just read or reread this past week.

“Trinity” (Asimov’s Oct 1984)

This is a novella, the first Kress story to receive a major award nomination, for a Nebula. Also, it’s the one Kress story Dozois chose for his first Best of the Best anthology, the one preceding the one under current Fb group consideration.

It’s a complex story of family relations and potential scientific discovery, and God. The scientific premise is about experiments with “twin trance,” in which holotanks and biofeedback are used to connect twins, perhaps to engage telepathy. Early experiments produced something more startling — a third entity inside the tank that appeared briefly. What was it?

And it’s about very complex family dynamics. Seena is the narrator. She conducted early twin trance experiments in which she got positive results but… all the subjects died. Since then she gave up the field and has become a museum curator. Devrie is her sister, who has fallen under the spell of a man who has set up an institute on an island in the Caribbean to study the twin trance phenomenon, thinking this might be away to perceive God. And offstage is their father, whose experiments in clones produced a clone of Devrie, Keith, long since adopted away to a family in New England.

Devrie uses Seena to contact Keith and bring him to the institute for an experiment to contact God (since Devrie and Keith as clones are virtually twins). There are some, as I said, very complex family dynamics along the way, some arguably incestuous. But the experiment goes ahead.

In Kress’ comments to this story in her collection of the same name, she mentions how someone told her that all her stories were about the absence of God. And maybe how that was true, to a point.

This story, without being too spoilerish, is about those who need to believe, and those who resist the idea of believing. And how those who need to believe resist the idea of something outside ordinary human conception.

\\

Two shorter stories.

“The Mountain to Mohamed” (Asimov’s Apr 1992) (Hugo/Nebula nominee, Locus Poll 2nd place)

This is about a near future in which “genescans” have enabled insurance companies to decline coverage to anyone with any kind of pre-existing condition. This has created an entire underclass of people who cannot legally be treated by the medical establishment. It involves a medical resident, Dr. Jesse Randall, who has made a covert deal to treat non-covered patients despite his hospital’s concern about malpractice suits. He gets a call, meets a group of men, is led to a house where a young girl is suffering appendicitis. He treats her, apparently successfully, but days later is served with a lawsuit. He realizes he’s been set up. But it’s not personal: it’s that underclass fighting back against the establishment, any way it can.

This is a fine story with many miniature character sketches. Patients he meets, each with their own story. Even a sidebar in which old people in Florida complaining about how nobody is willing to work anymore. (A perennial complaint.) The way Dr. Jesse finds to work outside the system, and prevail despite it, is inspiring, and moving.

At the same time, everyone dies of something, eventually, so what is the logic for not denying treatment for everyone?

\

“Nano Comes to Clifford Falls” (Asimov’s Jul 2006)

Here’s a story I had never read until this week.

The story is set in a rural town in which the narrator, Carol, is weeding her garden, when she hears that nanotech is coming to her town. (The city got it earlier.) Four machines are installed downtown. The mayor makes a speech. Within weeks the town has changed; everyone has flashy new cars, new clothes, even parts of new houses. Meanwhile, Carol tends her children through sickness and health. Then the men start quitting their jobs, because why work? The teachers quit. Carol takes it upon herself to home-school her own children, and the neighbors’. And things get worse, especially in the cities. Carol, and the others, take matters into their own hands, and begin a new society.

This is a cute, sweet, story, but it’s not science fiction (there’s no consideration about how the nanotech machines work, how they’re powered, where their resources come from, etc.), it’s a parable. The nanotech machines might as well be bags of magic. Ultimately it’s about how people react to it, of course: as the story puts it, those who like to work, those who don’t. And their fates are like the fates of lottery winners.

\\

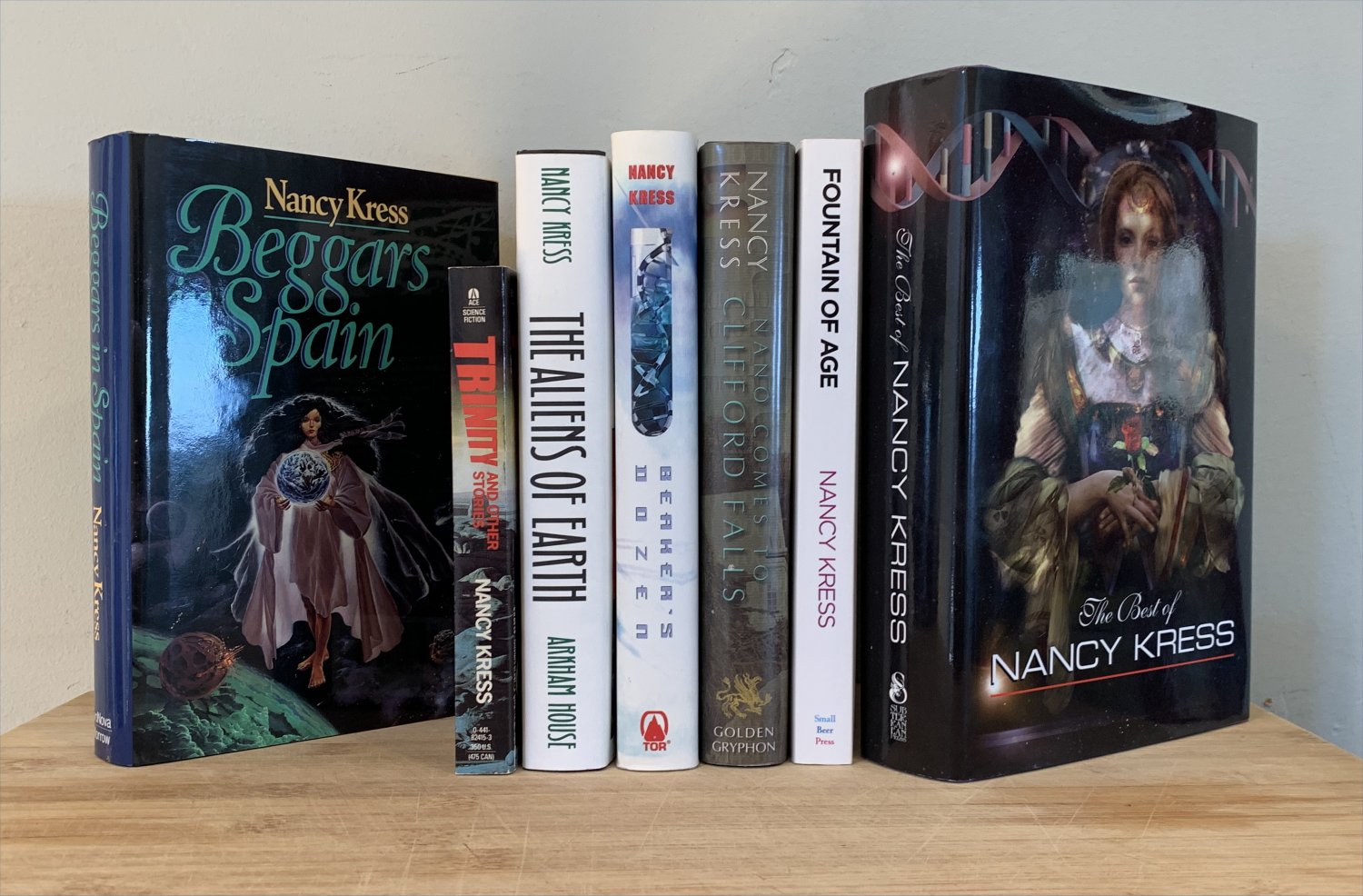

Finally I’ll note that Nancy Kress has been a prolific writer of both novels and short fiction for going on four decades now, and there are significant stories by her that I’ve never read, in particular the novellas “Fountain of Age” (2007) and “The Erdmann Nexus” (2008). Also, I did read “And Wild for to Hold” (Asimov’s July 1991) a novella published just a few months after “Beggars in Spain,” and I recall liking that even more than “Beggars in Spain.” But I don’t have notes on it, and will need to reread it. For what it’s worth, it’s the first story in her Best of Nancy Kress, while “Beggars in Spain” is the last in that book. Her own selected bookends.