This week’s Sunday novella is “Tendeléo’s Story” by Ian McDonald. It was first published as a chapbook by PS Publishing (in the UK), both in hardcover and paperback, in 2000. Subsequently it’s been published, aside from in the Dozois anthologies under review, in The Best of Ian McDonald in 2016 and in Neil Clarke’s anthology Not One of Us in 2018. I have the paperback edition of the chapbook, copy 25 of 500, signed by the author (whom I’ve never met).

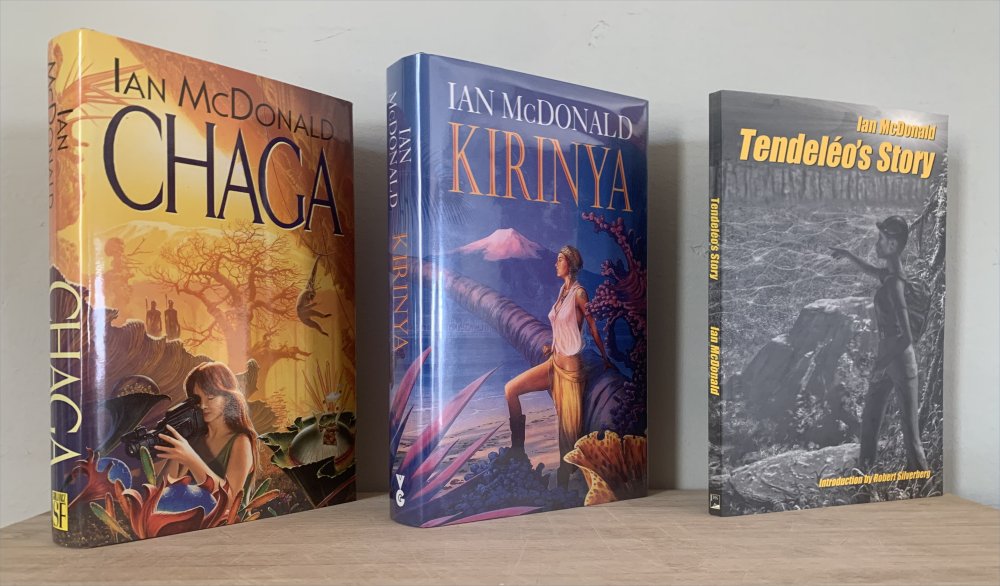

The story is part of the author’s “Chaga” sequence, following the novelette “Toward Kilimanjaro” (1990, also reprinted in his Best of) and the novels Chaga (1995, aka Evolution’s Shore in the US) and Kirinya (1998). The novels, I gather (I haven’t read them), tell much more about the origin of the alien “packages” that land on Earth and transform its biosphere, and are told from the points of view of Western scientists and journalists.

In contrast, as the title here suggests, the focus is on a single character, a resident of a small town in Kenya, as the alien Chaga infestation slowly moves toward her area. Tendeléo Bi, born 1995, is 13 when this happens, and soon UN officials are showing up to test the residents for infection and to direct their evacuation. In the commotion confidant and defiant Tendeléo and her sister decide to go see the edge of the Chaga themselves, a trip which gives McDonald the opportunity to fill readers in about the background of the Chaga if they’ve not read the earlier novels. We then follow Tendeléo and her family as they are evacuated to a shanty town in Nairobi, and live in squalor until rescued by a fellow pastor of Tendeléo’s father. Ever-determined, she hunts for jobs and gets one as a runner for a drug lord. And she blackmails an American embassy worker to get a chip ID that allows her escape the country.

The story switches POVs between hers and that of a man in Manchester, England, named Sean, who encounters her as a singer in a music club and immediately falls in love. They move in together, and discover that she’s already been affected by the Chaga — she heals very quickly, the nanoprocessors of the alien infection rebuilding her body. Health officials quickly deport her. And Sean goes to Africa to find her. For all the grimness and otherworldly terror implicit through most of the story, the story ends happily, even movingly, the coming of the Chaga regarded by the locals in Kenya as a chance to rebuild their world.

The tension here is between “First World” values — to destroy or at least control the alien invasion — and third world values, those of the locals directly affected, who discover the change the Chaga brings is not necessarily to be feared. Perhaps this was McDonald’s motive for revisiting the story, to experience it first-hand, so to speak, understand it from the inside. Also, this was about the time McDonald began setting books and stories in non-Western locales: India, Brazil, Istanbul. The grand theme here may be the increased inability of the Westerners to understand a world and a universe in conventional terms (the enormous mobile base of the UN scientists can do nothing to stop it; Christians are baffled trying to fit the reality of Chaga into their traditional mythology), giving way to direct experience and willingness to change.

McDonald is a pithy philosopher and historian.

Page 78:

For a thousand years Christianity had ruled England with the question: ‘Why?’ Build a cathedral, invent a science, writing a play, discover a new land, start a business: ‘why?’ Then came the Elizabethans with the answer: ‘Why not?’

Page 22, about Tendeléo’s father’s faith:

It was that it was strong in the small, local questions because it was weak in the great ones.

Page 51, contemplating what the death of a man means:

A man dies, and it is easy to say when the dying ends. The breath goes out and does not come in again. The heart stills. The blood cools and congeals. The last thought fades from the brain. It is not so easy to say when a dying begins. Is it, for example, when the body goes into terminal decline? When the first cell turns black and cancerous? When we pass our DNA to a new human generation, and become genetically redundant? When we are born?

And of course the Chaga, whose presence and description evokes Ballard and Wyndham, whose invasive catastrophes were however set in England. Page 26:

It was as though someone had cut a series of circles of coloured paper and let them fall on the side of the mountains. The Chaga followed the ridges and the valleys, but that was all it had to do with our geography. It was completely something else. The colours were so bright and silly I almost laughed: purples, oranges, lots of pink and deep red. Veins of bright yellow. Real things, living things were not these colors… I saw jumbles of reef-stuff the colour of wiring. I saw a wall of dark crimson trees rise straight for a tremendous height. The trunks were as straight and smooth as spears. The leaves joined together like umbrellas. Beyond them, I saw things like icebergs tilted at an angle, things like open hands, praying to the sky, things like oil refineries made out of fungus, things like brains and fans and domes and footballs. Things like other things. Nothing that seemed a thing in itself. And all this was reaching towards me.