-

- What psychology is good for, and its recent accomplishments;

- The idea of Ostranenie, a kind of defamiliarization, which of course is one of those things science fiction does at its best.

Big Think, Elizabeth Gilbert and Nick Hobson, 1 Oct 2023: Is psychology good for anything?, subtitled “Recent high-profile instances of fraud in psychology have led some to wonder if there’s anything useful about the field at all.”

Key Takeaways

• Psychology has been under fire for over a decade for problems with reproducibility. Recent high-profile cases of alleged fraud against researchers at Duke and Harvard have brought the field’s troubles back into the spotlight. • One researcher suggested that if discarding a substantial number of psychology studies has a negligible effect on our understanding of human nature, then perhaps psychology is irrelevant. • However, the field of psychology has made many reliable, important contributions to our understanding of the mind and behavior. Some of these contributions are so well-established and widespread that we fail to appreciate their impact.

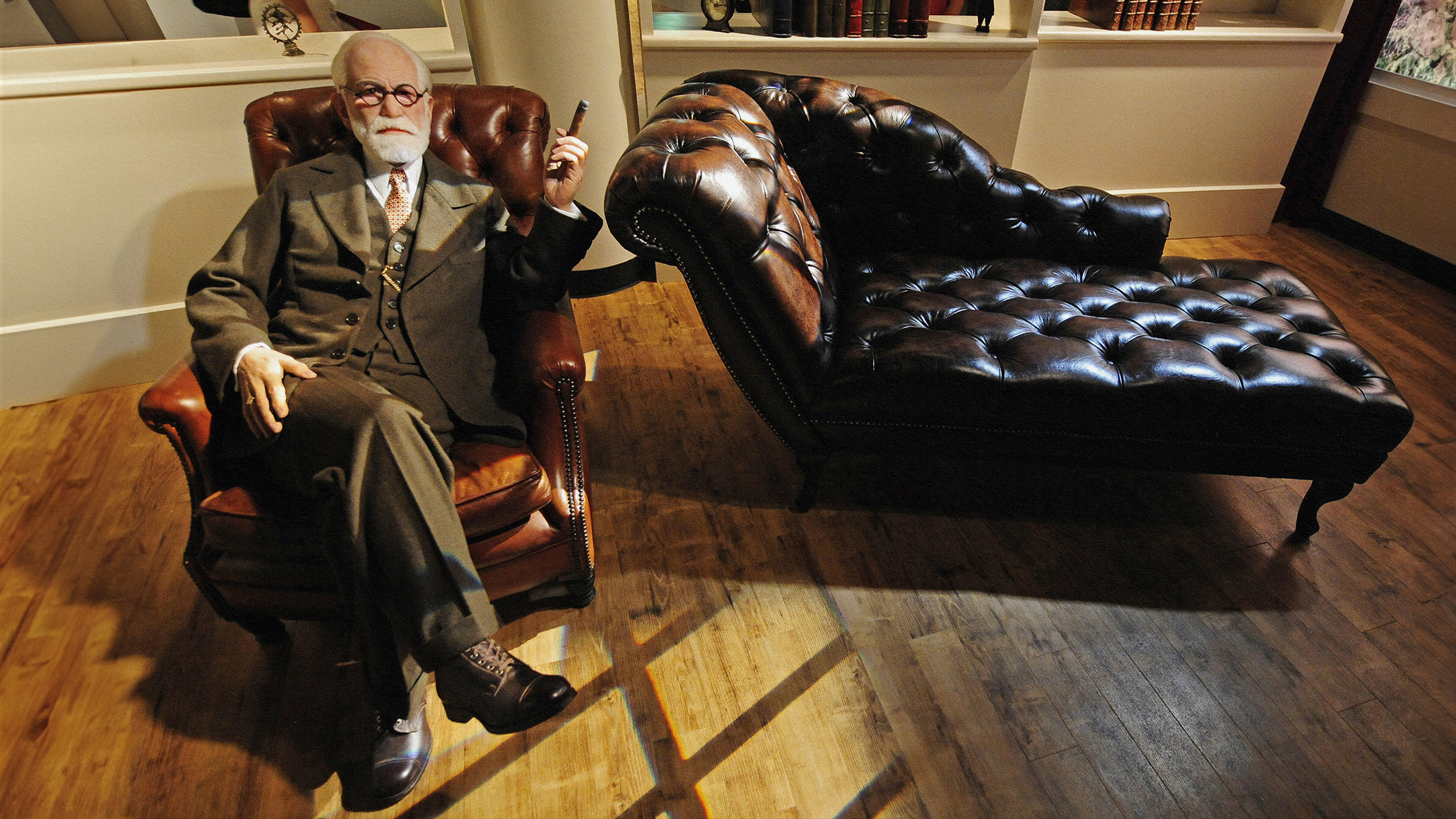

First some comments of my own. First, I think a lot of people still conflate psychology with psychiatry, the latter being a field of medicine concerned with mental conditions, more colloquially seen as involving counselors who sit people on sofas to discuss their personal situations. While psychology is the scientific study of the mind and behavior. It may be easy to dismiss psychiatry as a lot of talk, but psychology too has been dismissed as a lot of theorizing without evidence. For all their influence, the ‘theories’ of Freud and Jung were mostly hypotheses, at best models, with precious little actual evidence to back them up. After a long time spent in “behaviorist” thinking — from people like Skinner and Pavlov — in which inner states of mind were irrelevant and all that counted was outward behavior, which could be ‘trained’ the way dogs are trained — the field became genuinely scientific, grounded in theory and validated through experiment, only in the last few decades. The grounding was via evolution, leading to the entire field of cognitive biases and their evolutionary rationales. This is the field that has fascinated me over the past 20 years, with books by Ariely and Shermer and Kahneman, which I have read and summarized here on my blog. And that’s my potted understanding of psychology.

To the article. The ‘hook’ to the piece is the idea that many published studies have failed to replicate, raising the suggestion of fraud, catnip to those who want to dismiss any science that conflicts with their ideological or religious convictions. While outright fraud does occur among scientists — who are people too, with the same motivations and biases as the rest of us (and who think they might get away with cheating, even though they must be aware, the way science works, that any such fraud would eventually be revealed) — such incidents are greatly exaggerated by the media, simply because they’re so rare, and thus “news.” More fundamentally, that scientific studies sometimes fail to replicate is simply an indication that, among all the sciences, all the easy stuff has been discovered and has become highly validated, while the newer studies are looking for subtle effects not easily distinguished from the among the ‘noise’ of any scientific experiment. It’s not surprising that some of them are not replicated. But that in no way discredits the core discoveries of all the sciences — including psychology.

Before we dive in, let’s define what we mean by “psychology.” Psychology is a field that involves the use of scientific methods, such as experimentation, for systematic observation and prediction of human behavior. (Psychoanalysis, dianetics, hypnosis, or any research areas that don’t practice such methods are pseudoscience, not psychology.) As a science, psychology must ensure it does indeed contribute to our understanding of the world with empirical observation, sound measurement, and, ideally, replicable results.

Here is what what was assumed true, before modern psychology:

Less than 50 years ago, economists assumed people were fully rational, juries assumed confident eyewitness were accurate, and news watchers assumed only evil people would do evil things. Only 20 years ago, most businesspeople believed that cultures from across the world made decisions in the same way, physicians assumed the brain and body were essentially independent, and politicians thought only young people and conspiracy theorists were particularly susceptible to misinformation.

I think many of the critiques of science, including psychology, quibble about details. While the big pictures these sciences have formulated over the past century, the past few decades, are relative solid, even if there are so many people who would prefer their conclusions to be false.

And here are the conclusions of modern psychology:

None of those notions are right, and these psychological corrections are now so well-established that they seem banal. We are fish surrounded by so much psychological water, we don’t even notice it. In case you’re still skeptical, here’s just a brief list of robust psychological findings that help us understand humans better and improve our lives.

- Effective treatments for depression, anxiety, and phobias

- The five-factor model of personality traits and how personality relates to life outcomes

- An understanding of typical childhood development and learning

- How memory is constructed and can be altered

- Executive function, inhibitory control, and how they interact with automatic processing

- How attention works, including inattentional blindness and task-switching costs

- Moral judgments and how they affect decision-making

- Many classic cognitive bias findings, including sunk costs, gain-versus-loss framing, and anchoring

- Motivation and the importance of basic human drives for autonomy, competence, and relatedness

The article ends by noting that reproducibility problems are not unique to psychology (though it doesn’t quite identify how I see the reason for this). And it mentions “Paul Bloom’s recent book” — Bloom is somewhat notorious for having written a counter-intuitive book, in 2016, called Against Empathy: The Case for Rational Compassion, in which he argues against empathy, as an honest emotion that focuses too closely on individuals, without taking any bigger picture into account. The recent book is Psych: The Story of the Human Mind, published last February, and I have ordered it in order to understand, beyond the issue of psychological biases, the conclusions of modern psychology.

\\\

Here’s another Big Think article, about an abstruse concept.

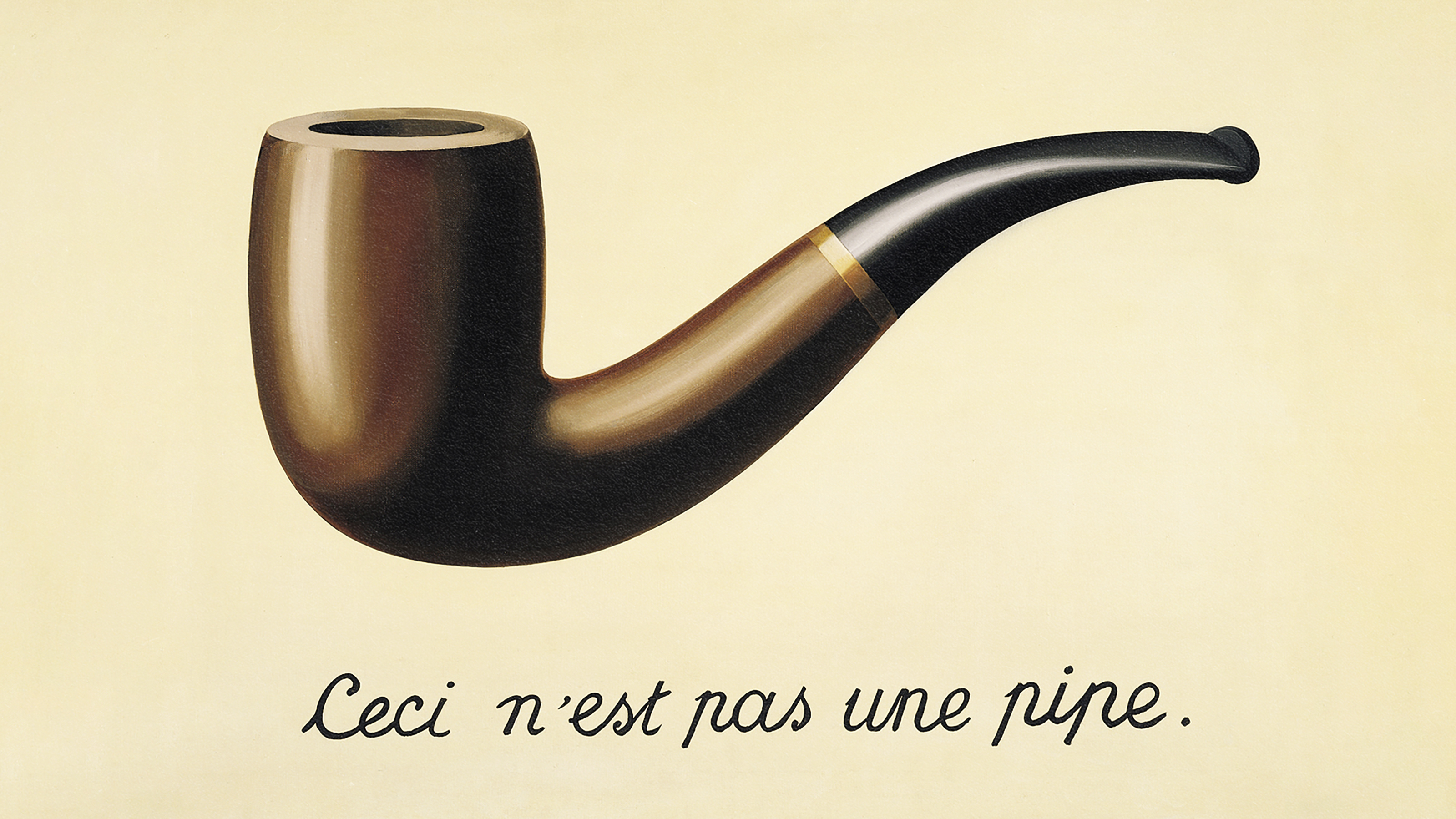

Big Think, Jonny Thomson, 29 Sep 2023: Defamiliarization: How “ostranenie” can redefine life, art, and business, subtitled “Defamiliarization is a common tool in the arts. Here we learn how seeing things from a different angle can lead to billion-dollar success.”

Key Takeaways

• Ostranenie — or “defamiliarization” — is a term from the philosophy of art. • Many successful companies, including Cirque du Soleil and Apple, have used ostranenie to great effect. Ostranenie is not the same as “pivoting” — it’s a way of seeing.

I’ll quote from this before commenting. End of the piece:

3 ways to apply ostranenie

Ostranenie is not quite the same as “pivoting,” where you reinvent your business or a product in a new way. It’s more a state of mind or way of seeing. Here’s how you can apply it in your business.

Love the problem. Every business sells a solution to a problem. They are satisfying a want. It’s easy to get swept away in the minutiae of the latest product design, and so we often forget to ask, “What is it we’re actually doing?” Netflix was selling entertainment, not DVDs. Steve Jobs was selling communication, not phones. What problem are you solving, and is this product the best way to solve it?

Bring in outsiders. Engage individuals outside of your industry or even hire consultants who don’t have a background in your field. These people can provide a fresh perspective, free from the biases and habits that industry insiders might have. Outsiders can challenge established norms and ask seemingly naive questions that can lead to breakthrough insights. In other words, you want to hire Tolstoy’s horse.

Embrace your inner alien. If you’re not inclined to hire an outsider, you can just as easily channel your inner alien. Imagine you are visiting extraterrestrials and trying to explain to them what you are doing. Imagine how they might respond. At your next meeting, take a leaf from the Nathan Pyle playbook: Get everyone to explain their job, task, or product in Strange Planet language. By looking at your product or service without preconceptions, you might see opportunities or issues that you’ve overlooked.

The third point gets at my point: this is what the best science fiction does.