- A long New Yorker essay about San Francisco, which acknowledges the minuses and the plusses;

- An ethereal track by Enya: “Exile”.

Another piece about San Francisco, a long piece in The New Yorker. Reading it now. Is it fair? Yes, reasonably.

The New Yorker, Nathan Heller, 16 Oct 2023: What Happened to San Francisco, Really?, subtitled “It depends on which tech bro, city official, billionaire investor, grassroots activist, or Michelin-starred restaurateur you ask.”

It’s long; about 50 page-downs on my screen. Opening para:

In the past few years, accounts of San Francisco’s unravelling—less like a tired sweater than a ball of yarn caught in a boat propeller—have spread with the authority of gossip or folklore. As the pandemic recedes, nearly a quarter of offices downtown are said to be vacant, the worst rate in the nation. Drug-overdose deaths are surging; reports of theft on downtown streets, including an almost two-hundred-per-cent increase in car break-ins in 2021, have crossed the national media to censorious response. “They took down the guardrails around personal responsibility,” the Wall Street Journal columnist Daniel Henninger declared on Fox News. In May, a local pet owner claimed that her Himalayan sheepdog began “wobbling” after eating feces possibly containing opioids and marijuana. Throughout the summer, Presidential hopefuls came to town to stand on grim street corners and record their horror for the cameras. (“It’s really collapsed because of leftist policies,” Ron DeSantis repined in his spot. Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., lamented the many Americans who “are on the precipice of ending up on a corner like this.”) Nine years ago, when HBO premièred the series “Silicon Valley,” a deadpan comedy lampooning the Bay Area’s life-style blandishments and hapless global power, the city seemed to exist in a helium balloon, floating ever upward. Now the same place is viewed as an emblem of American collapse.

Obviously, the pandemic happened, which emptied out downtown; and increased inequality, driven by Republicans with their tax cuts for the wealthy, has exacerbating homelessness. Those would be my two quick takes. And these things have happened in other cities; yet it’s easier to be homeless in west coast cities, where the weather is nice year-round.

The article is anecdotal, with the writer visiting, first, an official charged with rehabilitating San Francisco’s businesses.

Striking observation (yes, the city is small):

But the city’s influence can also be measured by its long shadow in Democratic politics. San Francisco, it’s easy to forget, is a small city, approximately seven miles long and wide—the distance from the World Trade Center to the top of Central Park. Its social sphere is startlingly compressed. One day, I stopped in a coffee shop to send an e-mail asking for an interview and, seconds later, heard a guy reading his phone across the room exclaim, “The New Yorker magazine wants to talk to me!” From this tiny ecosystem the political careers of the nation’s Vice-President, the governor of its most populous state, the recent longtime Speaker of the House, and (until last month) the most senior Democratic member of the Senate emerged. The city’s politics can seem preternaturally charged.

San Francisco is “a million shades of blue” comments one city supervisor. More discussion of car break-ins and drug dealing. Police priorities.

Given San Francisco’s dearth of housing and glut of offices, many people had raised the possibility of residential conversions. “It is not an easy task, but one that other cities have done with regulatory changes and financial incentives,” Rich Hillis, the city’s planning director, told me. In July, the mayor sent a letter inviting the University of California system to create a new campus downtown. Still, Dennis Phillips noted, many conversions would likely cost more than developers could expect to earn, making it a hard sell: “It’s only twenty per cent of our strategy downtown.”

Again, something going on in many cities. It’s a huge social swing, going on before our eyes; the collusion of homelessness and empty downtowns; a swing that will be remembered in history, as a legacy of covid. (And again, that UBI discussed last post could well be applied for problems like these, at minimal expense to the wealthy; but Republicans would never stand for it.)

Then about the A.I. industry. And some reality-checking:

In public declarations, Westfield—like Gump’s—laid the blame for its lack of business on the condition of San Francisco’s downtown. But in the past forty years the number of malls in the United States has declined by nearly three-quarters, and a tour of downtown San Francisco today, its streets packed, its bars busy, can seem an odd me-or-your-lying-eyes experience. By many measures, San Francisco is the safest it has ever been. Violent crime is a third of what it was in 1985, and currently twenty per cent below the average of twenty-one major American cities.

The city has a triple-A credit rating. Most of its residential neighborhoods are clean and green and bustling. With the exception of the Tenderloin, the neighborhood from which most dire imagery comes, a walk through San Francisco is a stroll around an affluent Pacific capital of small bookstores and night markets and weekend festivals—so much so that one can almost wonder where the idea of a city in decline emerged.

Long article. It ends thus. Here’s where they are.

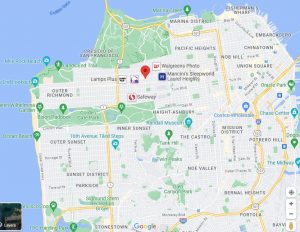

Traffic washed by. We were sitting at a sidewalk table at a café on the corner of Arguello and Clement, near the apartment where Bindman lives and works—the nonprofit has no offices. I had taken a long walk across San Francisco, through the neighborhoods and parks and out toward the ocean. It was a bright and sunny day with tufted clouds and breezes sweeping in off the Pacific, and I allowed myself to think that the city had not in years felt quite so set for possibility, so open and warm. “I think what SF New Deal represents is the very obvious answer, which is: everyone. Everyone is responsible,” Bindman said. He took a sip of coffee and looked up. “The only solution that’s a real solution is a solution in which everyone is involved.”

Bottom line: things change. People adjust. Conservatives always see change as impending catastrophe, and will cherry-pick examples, in this case, from the worst neighborhoods in cities to promote their idea the Democratic-led cities are hellholes. They are not part of the reality-based community. They’re wrong.

\\\

Lots of political posts I could post; but for today let’s end with an ethereal song by Enya, from 1998. “Exile”, from the album Watermark.