- The Atlantic‘s Peter Wehner on how evangelicals don’t actually follow Jesus’ teachings;

- With an aside about my own attempts to cross the political divide;

- Robert Reich on his history with the New Left and how Trump arose out of the Democratic presidents taking organized labor — the focus of the Old Left — for granted.

The Atlantic, Peter Wehner, 3 Mar 2024, Where Did Evangelicals Go Wrong?, subtitled “Jesus told us to love our enemies. And yet so many have embraced hostile politics in the name of Christianity.”

Very long piece, adapted from a forthcoming paper. (21 screens on my monitor.) I won’t try to summarize all of it, but I will at least note what caught my eye as I skimmed it. The essay opens with a familiar account of our current political divide, for several paragraphs.

America is a riven society. Political divisions have been on the rise for years. The gap between the Republican and Democratic Parties has grown in Congress, and the share of Americans who interact with people from the opposing party has plummeted. Studies tell us, “Democrats and Republicans both say that the other party’s members are hypocritical, selfish, and closed-minded, and they are unwilling to socialize across party lines.”

Many Americans read news or get information only from sources that align with their political beliefs, which exacerbates fundamental disagreements not just about policies but about basic facts.

So-called affective polarization—in which citizens are more motivated by who they oppose than who they support—has increased more dramatically in America than in any other democracy. “Hatred—specifically, hatred of the other party—increasingly defines our politics,” Geoffrey Skelley and Holly Fuong have written at FiveThirtyEight. My colleague Ron Brownstein has argued that the nation is “confronting the greatest strain to its fundamental cohesion since the Civil War.”

One might reasonably expect that Christians, including white evangelicals, would be a unifying, healing force in American society. After all, the apostle Paul wrote that Jesus came to tear down “the dividing wall of hostility” between groups that held profoundly different beliefs. “Blessed are the peacemakers, for they will be called the children of God,” Jesus said. In that same sermon, Jesus also said, “I tell you, love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you.” Even if those goals have always been unattainable, they were seen as aspirational.

Yet in the main, the white evangelical movement has for decades exacerbated our divisions, fueled hatreds and grievances, and turned fellow citizens into enemies rather than friends. This isn’t true of all evangelicals, of course. The movement comprises tens of millions of Americans, many of them good and gracious people who seek to be peacemakers, including in the political realm. They are horrified by the political idolatry we’re witnessing and the antipathy and rage that emanate from it. But it is fair to say that this movement that was at one time defined by its theological commitments is now largely defined by its partisan ones.

As an aside — I tend to be a solitary, self-sufficient person and so do not “socialize” in any meaningful sense with hardly anybody, except family (on my partner’s side), Facebook friends, and colleagues in the science fiction community, and even the latter mostly through Facebook. Still, my partner and I routinely chat with neighbors on our street, without wondering about their political leanings. Of course, we’re in Oakland, the Bay Area. California! To a large extent, I suspect, the people one interacts with are driven by location and profession or common interests. I do know that my brother’s family in small-town Tennessee exhibited their anti-VAX conspiracy theorizing back when COVID broke out, in early 2020, and when I attempted to engage them, they cut *me* off.

Back to the article — what caught my eye was the very next paragraph.

For much of the 20th century, evangelicals were disengaged from American politics, in part because of the humiliation of the 1925 Scopes “monkey trial,” in which one of the nation’s most prominent evangelicals and politicians, William Jennings Bryan—a populist Democrat who ran for president three times—prosecuted the case against a high-school teacher, John T. Scopes, who was charged with violating Tennessee state law for teaching evolution in schools. Bryan, who also testified, won the case but hurt his cause. (Scopes was found guilty, but the verdict was overturned on a technicality.) Outside of fundamentalist circles, Bryan and the movement he represented, which attacked the empirical findings of science, became the object of ridicule.

Of course I know about the Scopes trial; I read the play version of it, “Inherit the Wind,” way back in high school, saw it performed UCLA, and have seen the movie two or three times. (Here’s a post about the movie from almost 10 years ago! Inherit the Wind.) And I know that my brother’s daughter attended Bryan College, where all instructors (last time I checked) have to swear allegiance to a literally-true Bible.

What I never realized, as this article implies, is that this incident so affected the fundamentalists that they changed their engagement with politics for decades.

The article goes on and on, with the rise of the religious right in the 1970s, its opposition to so many social advances of that era (again, Jesus?), the rise of Jerry Falwell, how until 1980 evangelicals tended to be more Democratic! Then Reagan, the Moral Majority, and evangelical opposition to American society.

Now, the writer is Christian, and is alarmed by the current state, and has ideas to repair it. Skimming, but I’ll capture these points:

- First, Christians need to reacquaint themselves with the Jesus of the New Testament, not the Jesus of the American right (or left). The real Jesus demonstrated a profound mistrust of political power and did not encourage his disciples to become involved in political movements of any kind.

- Second, Evangelicals also need to develop a theory of political and social engagement that is far more comprehensive and careful, mature and informed, textured and sophisticated.

- A third thing that needs to happen is for many politically active Christians to move away from a spirit of anger toward understanding, from revenge toward reconciliation, from grievance toward gratitude, and from fear toward trust.

- The fourth thing Christians can do to strengthen their public witness and the state of our politics is internalize and act on the lessons from the parable of the Good Samaritan, which speaks to this moment in a powerful way.

Non-Christians have little issue with Jesus’ teachings — well, maybe except for the cultish part about Jesus insisting his followers abandon their families — our issue is that those teachings seem completely at odds with the way evangelicals act in the real world.

The big big picture is that, over the past century or two, the investigation and discovery of reality has gradually undermined the myths that inform Christianity and all the other religions. And so the religious reject those discoveries, preferring their simplistic myths and tribal solidarity.

\\\

Robert Reich, 1 Mar 2024: The Old Left, the New Left, and the Left Behind, subtitled “The roots of Trumpism, Part 9”

Also at Alternet, 2 Mar 2024: Opinion | The roots of Trumpism

He begins by offering some personal history, about how he discovered and embraced the “New Left” in the 1960s. The Old Left was about the labor union movement.

The New Left focused on the needs of people fortunate enough to take material comfort for granted — mostly college students, college graduates, and professionals. It sought to protect consumers from unsafe products, reduce pollution, win new rights for women and people of color, reduce dire poverty, and spread participatory democracy.

My introduction to the New Left was the “Port Huron Statement,” issued by a group of mostly white, middle-class college students from the University of Michigan. Its main author was a young activist named Tom Hayden, a recent graduate of the University of Michigan and editor of the Michigan Daily, who was then just 21 years old. Hayden went on to become president of Students for a Democratic Society.

A friend had lent me a copy. I read it in the summer of 1963 on the front porch of my grandma Frances’s cottage in the Adirondack Mountains.

From its very first line, I was transfixed. “We are people of this generation,” it read, “bred in at least modest comfort, housed now in universities, looking uncomfortably to the world we inherit.”

It seemed to be talking directly to me. I wasn’t yet in college but was planning to choose one that fall. And although reared in modest comfort, I felt increasingly uncomfortable with the direction America was taking.

Meanwhile, segregationists and white supremacists were on the rise in reaction to the Civil Rights Movement. He took the Port Huron Statement to heart. It concerned foreign policy, the arms race, the American dream that “encouraged consumerism and conformity,” and university education.

In response to all these failings, the Statement called for participatory democracy — across college campuses, in the South, and in inner cities. Seeing the effectiveness of the young civil rights protestors of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the authors believed that ordinary citizens — particularly students — could create change through nonviolent means.

Reich adopted it as his manifesto. But he came to realize he left out “a big portion of America — the non-college working class.” And Democratic presidents took organized labor for granted. The essay finishes:

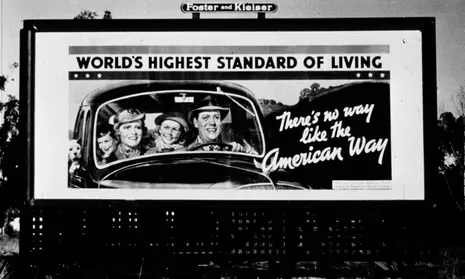

The consequence of all this was that by 2016, millions of American workers — the vast majority of them with no college education and no union to support them — had been left behind. Their wages were stagnant. They could be fired at will. Their lifespans were shrinking.

The economy no longer offered them the means of doing better. Politics no longer offered them a voice.

Into this void came Donald Trump, who as president gave large tax cuts to the wealthy and large corporations but somehow made the working class — especially the white working class — feel he was speaking to and for them.

He channeled their cumulative anxieties and frustrations into bigotry, nativism, and hate toward Muslims, Mexicans, Democrats, bureaucrats, and “coastal elites.” He took a wrecking ball to democracy. He is now running for president again.