- Follow-up to yesterday’s topic about utopias and dystopias, and Star Trek;

- How Trump and Vance have no idea about the reasons for Obamacare;

- Robert Reich on how Trump appeals to base hatefulness;

- Charles M. Blow on Trump’s bigger agenda;

- And David Lay Williams appeals to Rousseau to explain Trump.

A follow-on to yesterday’s topic. About those dreams of utopias. At the risk yet again of oversimplifying a vast literature on no doubt complex and subtle themes, very roughly one might align utopias with democracies, egalitarianism, justice, and being ‘woke’; and dystopias with tribal values and demonization of other ‘tribes’ and being ‘anti-woke’. It all boils down to different psychological takes on how the world should be. That range will likely never change. (And in ways we can only dimly imagine, such diversity could well be beneficial for the long-term survival of the species.)

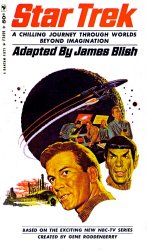

Star Trek, at its beginning, was a kind of utopia. Gene Roddenberry, the show’s creator, explicitly laid out a premise in which the ancient conflicts of the past (meaning the 20th century) had been overcome, and peace and understanding (this was the ’60s) ruled over all, even among some of the alien civilizations the Enterprise encountered. From the beginning writers complained that lack of conflict between characters made stories difficult to write. And over the decades, as the movies were made and subsequent TV series were produced, Roddenberry’s vision got pretty watered down. Even today, you see references to this or that episode in one of the series as one that “Gene Roddenberry would have hated.” Well, that’s narrative drift for you. The same thing happens in every franchise. Thus the sympathetic creature created by Dr. Frankenstein became a rote monster in virtually all the movies and sequels. And so on. Another topic.

\\\

Now to cover a batch of the past few days’ media links.

Religious fundamentalists don’t need to learn; all answers are already known (see: Bible) and are nonnegotiable. Conservatives/Republicans have become barely distinguishable from them. They don’t learn either; it’s naive to think that they can. Thus their persistent invocation of “trickle-down economics,” the notion that tax cuts for the wealthy will benefit everyone else. Never has happened. Here’s another example.

NY Times, Paul Krugman: Trump Learned Nothing From the Obamacare Debate. Neither Did Vance.

The gist here is that both Trump and Vance seem to have no idea why the decisions that went into Obamacare were made.

But Vance’s remarks were bad either way. Apart from anything else, he sounded like someone completely unaware of the history of health care economics and the reasons we ended up with the policies we have — someone who completely missed the debates that led to the creation of the A.C.A., a.k.a. Obamacare.

We don’t need to speculate about how his proposal, such as it is, would work, because we’ve seen this movie; that’s exactly how health insurance worked before Obamacare went into effect in 2014, after which insurers were prevented from discriminating based on medical history. Under the pre-Obamacare system, insurers often refused to cover Americans with pre-existing health conditions or required that they pay very high premiums — which meant that they effectively denied health care, in many instances, those who needed it most.

Republicans tend to be libertarian/selfish in these matters, Krugman acknowledges.

Now, you could ask why healthy Americans should subsidize the sick. One answer is that today’s healthy may be tomorrow’s sick. But beyond that, even relatively conservative Americans tend to believe that there’s an element of social justice involved, that a wealthy nation shouldn’t abandon millions of its citizens who have health problems that insurance companies don’t want to deal with.

This speaks to the social contract, the common good, and why we live in a society with both freedoms and obligations, rather than a collection of libertarian strongholds protecting their own while letting everyone else rot. The latter tribalist approach is apparently what Trump and Vance advocate. WWJD? is never a consideration for them.

\\\

More evidence of Trump’s appeal to his followers’ essential tribalism.

Robert Reich: Trump’s hate, subtitled “‘Hate’ has become his signature utterance”

Many explanations have been offered for why two assassination attempts have been made on Trump over the last two months. Some blame easy access to assault weapons; I’m sure that’s part of it.

But the real incitement to violence in America is hatefulness — hate speech, fearsome lies, and dangerous, paranoid rumors — the epicenter of which is Trump.

Trump blames the intensifying climate of violence on Kamala Harris and the Democrats: “Their rhetoric is causing me to be shot at,” he said. “Because of this Communist Left Rhetoric, the bullets are flying, and it will only get worse!” he wrote in a social media post. Trump’s campaign has circulated a list of so-called “incendiary” remarks Democrats have made against Trump and posted video clips from top Democrats calling him a “threat.”

JD Vance says “we cannot tell the American people that one candidate is a fascist and if he’s elected it is going to be the end of American democracy.”

Hello? Calling Trump a fascist and a threat to democracy is not inciting violence; it’s telling the truth.

\\\

Along the same lines.

NY Times, Charles M. Blow, 18 Sep 2024: Trump’s Bogus Claims About Haitians Are Part of a Bigger Agenda

So what is this bigger agenda? Trump knows his base and knows how to play it. As Republicans have before him.

Trump has spent years barking about the purported scourge of immigration from Mexico and Central and South America, but that didn’t quite produce the poster villain that would perfectly focus public sentiment — it didn’t give him Ronald Reagan’s “welfare queen” or George H.W. Bush’s Willie Horton.

But Trump knows what works and how to lean into it. He began his 2016 presidential campaign by disparaging Mexican immigrants as people “bringing crime” and “bringing drugs” and as “rapists,” but he would later train his rhetoric on inner cities, painting Black Chicago, especially, as a lawless hellscape.

The mythos of Black savagery remains so imprinted on the American psyche that many Americans are quick to believe it, even without evidence. And so Trump has again turned to it; it seems clear that his attack on Haitian immigrants, who are of African descent, is in part an attempt to link broader anti-immigrant sentiment with anti-Black sentiment. It goes hand in hand with his characterization, a few years ago, of Haiti as a “shithole” — a place from where people, he seems to want us to think, are of course uncivilized and therefore incapable of blending into the American melting pot.

But it’s even more than that.

The article goes on to recall the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, and similar attitudes toward Indigenous peoples (“Kill the Indian in him and save the man”). Trump’s adviser Stephen Miller now wants to “strip citizenship rights from naturalized immigrants.” How far back would he go, I wonder? My ancestors were naturalized immigrants. For Miller to set a date would give away his racist motives.

\\\

And one more along the same theme, while appealing to the larger topic of human nature, and history.

NY Times, guest essay by David Lay Williams: Why Is Trump Spreading Rumors About Haitian Immigrants? Rousseau Knows.

(The debate about whether Rousseau or Hobbes was more correct about human nature continues to this day; see recent books that I’ve reviewed here by Pinker, Bregman, Rauch.)

Fractious rhetoric has always been a feature of politics. But it is still difficult to discern why such appeals resonate so much now. Taking a few steps back to an early diagnostician of divisiveness, the prickly 18th-century Genevan philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, can help.

Rousseau’s “Discourse on the Origin and Foundation of the Inequality of Mankind,” in which he explored the origins and effects of economic inequality on societies, is perhaps his most enduring work. In it, he observed that unequal societies are inevitably divided into two diametrically opposed classes, rich and poor. While the poor struggle to liberate themselves from poverty and oppression, the rich and powerful employ clever techniques to maintain their wealth, power and status.

Well, appeals still resonate because they appeal to base human nature, which hasn’t changed.

Inequality wasn’t new to the 18th century. It had been a central attribute of the feudal world. But its ability to survive feudalism’s decline during the Enlightenment was alarming, and it became increasingly important for Rousseau to understand the techniques by which it was maintained.

One tool that sustained inequality, Rousseau observed, was divisiveness. It is, he observed, in conditions of extreme inequality that cynical leaders would foment “everything that might weaken men united in society, by promoting dissension among them” and sowing the “seeds of real division.” Those in power accomplish this, he speculated, by fostering a “mutual hatred and distrust, by setting the rights and interests of one against those of another.”

So… creating divisiveness is a way for the wealthy to distract the poor from pondering their sorry state. This is consistent with commentaries recently about how Trump and his lackeys focus on certain topics — like the border, like Haitians — precisely to distract people from realizing they don’t have coherent policies about the economy, or healthcare.

(Trump has only “concepts of a plan” about healthcare. Here’s another: ‘Major smash’: Trump ‘incoherent’ when asked for specifics on vow to bring down prices . Do his supporters actually listen to him speak? Are they paying attention? Probably not.)