Let’s look at some non-political items today.

- Three critical thinking tools used by Daniel Dennett;

- Eight principles of lifelong learning from an astrophysicist;

- Adam Lee on our solarpunk future — technology that exists now, but isn’t widely distributed;

- Scientific American on commonalities in the world’s music;

- And Elizabeth Kolbert on the threat of Greenland’s ice melting.

Big Think, Kevin Dickinson, 23 Oct 2024: 3 brilliant critical thinking tools used by Daniel Dennett, subtitled “The late philosopher suggested adding a couple of “Occam’s heuristics” to your critical thinking toolbox.”

Key Takeaways

• An important question to ask yourself is, “What if I’m wrong?” • “Occam’s razor” helps you shave the unnecessary junk from your ideas, while “Occam’s broom” helps you see relevant facts others may be sweeping under the rug. • While Dennett recommends these tools, he adds that engaging with others is vital for uncovering the best explanations for how things truly work.

The three are Occam’s razor (“No superfluous junk added into the theory” as he puts it), Occam’s broom (be careful not to sweep relevant facts “under the rug”), and Engage with Others. The essay doesn’t mention it, but Dennett wrote a whole book about 10 years ago full of such ideas, which I partially reviewed here, called INTUITION PUMPS AND OTHER TOOLS FOR THINKING.

\\\

Here’s another set, from the same site on the same day.

Big Think, Ethan Siegel, 23 Oct 2024: 8 lessons on lifelong learning from an astrophysicist, subtitled “Beyond stars, galaxies, and gravity, studying the fundamental workings of nature reveals widely applicable lessons for learners everywhere.”

Key Takeaways

• In order to become an astrophysicist, you have to learn not just math, physics, and astronomy, but also a profound series of lessons about thinking, problem solving, and learning itself. • Those lessons have applications that extend far beyond scientific or academic pursuits, and can help learners of all ages and from all walks of life. • These eight profound lessons range from ignoring noise to knowing when to listen to someone with more expertise than you, and they can help everyone economize their efforts to achieve maximal results.

These aren’t attributed to any particular great scientist; they seem to be Ethan Siegel’s distillation of some basic principles of science, especially in physics and astronomy. Roughly the same principles apply, of course, in dealing honestly with the real world in all sorts of situations. I’ll just list them; the article has several paragraphs about each point.

- The most critical step in problem-solving is setting up the problem correctly.

- A sufficiently close approximation is often just as good as an exact result.

- Keep an eye out for the underlying relationships between things you can observe or measure.

- Always be aware that your expertise in a subject, no matter how deep it runs, is limited.

- Knowing where to find the information you need is more important than memorizing it.

- Knowing which aspects of a puzzle are extraneous can keep you from succumbing to distractions.

- There’s almost always a deeper layer to reality than our current understanding indicates.

- When things don’t add up, be prepared to re-examine your underlying assumptions.

\\\

OnlySky, Adam Lee, 22 Oct 2024: Glimpses of the solarpunk future

As William Gibson said, the future is already here. It’s just not evenly distributed.

We already possess technologies that could create a world that’s more sustainable, prosperous and equitable than the world as it is today. What’s holding us back is that those technologies haven’t rolled out to the majority of humanity. But that day is coming, and when it arrives, our civilization will undergo a dramatic transformation.

As Lee says below, none of the topics here are science fiction. They’re just not broadly deployed yet. The topics: solar power; passive houses and heat pumps; automated manufacturing; high-tech precision farming; high-speed electric trains; self-driving taxis and the end of car culture; green energy to make communities resilient to climate change.

This is an ambitious picture, but none of it is science fiction. Green energy, 3-D printers, autonomous robotics and these other technologies already exist. Some are more advanced than others, but there’s no doubt the ones that are lagging will keep improving.

There is room to doubt if these technologies will eventually become available to everyone, or whether they’ll remain playthings of the rich and the privileged. But that’s a problem we can solve through the political process. If enough of us demand it, we can bring forth a solarpunk utopia for everyone. It may not be as far off as you think.

\\\

I’ve long noted similarities in what makes pop songs “catchy.” Invariably it’s something steadily rhythmic, or a point at the which the melody leaps into a higher register, even if only for a couple notes. This study is more subtle.

Scientific American, Allison Parshall, Duncan Geere, & Miriam Quick, 15 Oct 2024: Hidden Patterns in Folk Songs Reveal How Music Evolved, subtitled “Songs and speech across cultures suggest music developed similar features around the world:

This is no surprise; modern pop songs, in particular, show striking similarities, almost formulas. So do works of traditional “classical” music. Works that break those patterns, like much of 20th century “classical” music, sounds strange precisely for that reason — and that’s why those composers tried to push traditional boundaries, to be creative, to see what would happen.

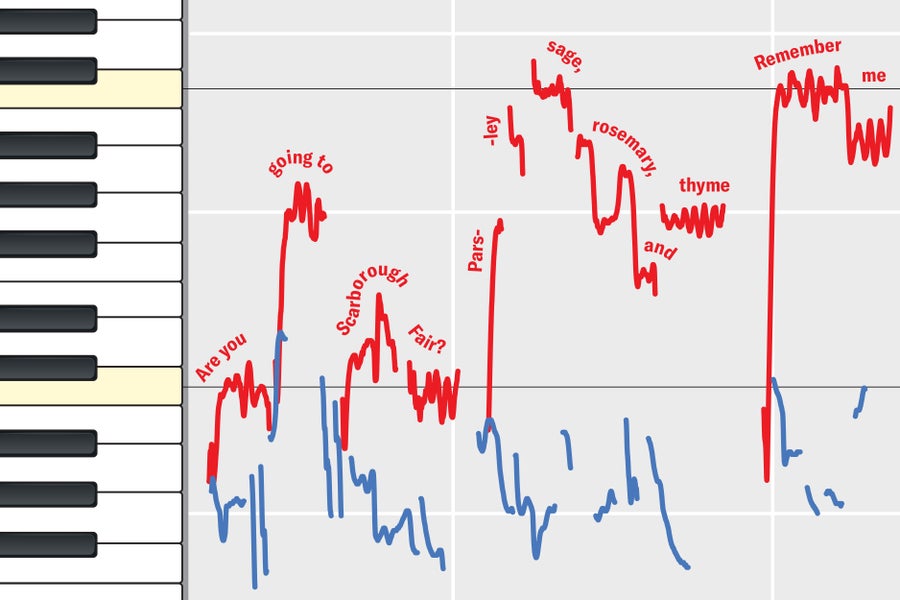

The chart visualizes two recordings of the English folk song “Scarborough Fair”—one sung, one spoken—by Patrick Savage, a study author and participant. The song unfolds at around half the speed of the spoken version, and its pitches are generally higher. They are also more stable, being centered on fixed musical notes, but with added expressive pitch fluctuations such as scoops and vibrato. In contrast, the spoken performance never settles on a pitch for long.

There are more charts and some more interpretations.

\\\

Elizabeth Kolbert, author of THE SIXTH EXTINCTION (reviewed here), was on KQED’s Forum program this morning, here (this page should eventually have a transcript), in response to her big article in The New Yorker earlier this month.

The New Yorker, Elizabeth Kolbert, 7 Oct 2024: When the Arctic Melts, subtitled “What the fate of Greenland means for the rest of the Earth.”

Yes, it’s bad (though the melting of Antarctica would be far worse), and Kolbert was blunt in her dismissal of climate change denialists. I won’t try to summarize this, just quote the first couple paragraphs for flavor…

In the middle of the night in the middle of the summer in the middle of the Greenland ice sheet, I woke to find myself with a blinding headache. An anxious person living in anxious times, I’ve had plenty of headaches, but this one felt different, as if someone had taken a mallet to my sinuses. I’d flown up to the ice the previous afternoon, to a research station owned and operated by the National Science Foundation. The station, called Summit, sits ten thousand five hundred and thirty feet above sea level. The first person I’d met upon arriving was the resident doctor, who warned me and a few other newcomers to expect to experience altitude sickness. In most cases, he said, this would produce only passing, hangover-like symptoms; on occasion, though, it could result in brain swelling and death. Belatedly, I realized that I’d neglected to ask how to tell the difference.

N.S.F. Summit Station—according to the agency’s many rules, this is how visiting journalists are required to refer to the place—was erected in the late nineteen-eighties. Initially, it was occupied only in the summer; now a small crew remains through the winter, when, at Summit’s latitude—seventy-two degrees north—the sun never clears the horizon. The station’s main structure is known as the Big House. It resembles a double-wide trailer and teeters almost thirty feet above the ice, on metal pilings. Arrayed around it are a weather station, also elevated on pilings; a couple of very chilly outhouses; several tanks of jet fuel; and an emergency shelter that’s shaped like a watermelon and called the Tomato. Some of the station’s residents used to sleep in tents, but a few years ago a polar bear showed up, so the tents have been replaced by metal sheds.

And then quote the final paragraph, which of course illustrates yet again the difficulty humans have with dealing with long-term threats. (Especially conservatives.)

Climate change is not like other problems, and that is part of the problem. What it lacks in vividness and immediacy it makes up for in reach. Once the world’s remaining mountain glaciers disappear, they won’t be coming back. Nor will the coral reefs or the Amazon rain forest. If we cross the tipping point for the Greenland ice sheet, we may not even notice. And yet the world as we know it will be gone.