Al-Khalili, Jim. 2022. The Joy of Science. Princeton. ***

Al-Khalili, Jim. 2022. The Joy of Science. Princeton. ***

Short but substantive book about the benefits of thinking more scientifically. Science is a process, not a belief system; scientific theories need to be falsifiable and testable, and so science is self-correcting, in spite of cultural contexts or the biases of individual scientists. Chapters concern how we know that some things really are true, and others are not; the messiness of real life, and to beware black and white thinking and “common sense”; how mysteries are attractive yet can be solved; you can learn to understand almost anything; value evidence over opinion; recognize your own biases as well as others’; don’t be afraid to change your mind; and stand up for reality over conspiracy theories and misinformation. Science is valuable as a reliable way of learning how the world works, because science itself works (thus our technological world), its principles can apply to everything, and it enriches us in an almost spiritual way. (post)

Angier, Natalie. 2007. The Canon: A Whirligig Tour of the Beautiful Basics of Science. Houghton Mifflin. * 1/2

Angier, Natalie. 2007. The Canon: A Whirligig Tour of the Beautiful Basics of Science. Houghton Mifflin. * 1/2

As the subtitle says, covering physics, chemistry, evolutionary biology, molecular biology, geology, and astronomy, along with basic principles of thinking scientifically, probabilities, and calibrations (scales). Useful, but the author’s style is cutesy, veering between ingratiating and grating. (post)

Asimov, Isaac. 1997. The Roving Mind. Prometheus Books. ***

Asimov, Isaac. 1997. The Roving Mind. Prometheus Books. ***

Collection of essays from 1983, reissued with tributes in 1997 following Asimov’s death in 1992. Asimov displays “methodical, cheerful, bluntness” (my words) in several essays about religious radicals (as much an issue in 1983 as now), dismissing the common arguments of creationists against evolution; replies to the common notion that science fiction authors (and readers) must surely “believe” in flying saucers, telepathy, and so on (they don’t); and has an efficient, logical argument about how, if telepathy existed, the world as we know it would make no sense. (post)

Brockman, John. 2019. The Last Unknowns: Deep, Elegant, Profound Unanswered Questions About the Universe, the Mind, the Future of Civilization, and the Meaning of Life. William Morrow. ***

Brockman, John. 2019. The Last Unknowns: Deep, Elegant, Profound Unanswered Questions About the Universe, the Mind, the Future of Civilization, and the Meaning of Life. William Morrow. ***

Editor and agent John Brockman’s books like this one pose a single question and invite two or three hundreds scientists to respond. In this book, the question is: what is a profound question that remains unanswered? The posts here about this book aren’t a review but rather my own proposed answers, as best as I can guess based on my own reading, to several dozen of these. Scientists include Gregory Benford, Jerry Coyne, Daniel C. Dennett, David Deutsch, Jared Diamond, Jonathan Haidt, Sam Harris, Nicholas Humphrey, and many others whose books I’ve read; and as many or more others unfamiliar to me. (post 1; post 2; post 3; post 4.)

Carroll, Sean. 2016. The Big Picture: On the Origins of Life, Meaning, and the Universe Itself. Dutton. *****

Carroll, Sean. 2016. The Big Picture: On the Origins of Life, Meaning, and the Universe Itself. Dutton. *****

CalTech physicist Carroll describes the perspective we gain from cosmology and science in how we view our world and our place in it: how that understanding is purely materialistic and non-supernatural, and how that’s OK. Carroll avoids the perils of reductionism through the idea of “poetic naturalism” and the notion that we use different kinds of ‘stories’ to describe the world at different levels of complexity or levels of emergence. He discusses how current understanding of physics rules out psychic powers (and life after death), and discusses evolution and the evident lack of ‘purpose’, why we can dismiss various arguments for a god, different ways of thinking [again, Kahneman], morality and meaning of life. He concludes with a list of “Ten Considerations” (rather than Commandments), things to keep in mind while deciding how we want to live. My post includes links to summaries of the book’s six sections on the author’s website, and my own summary and comments on his “Ten Consideration.” (post)

Dawkins, Richard. 1998. Unweaving the Rainbow. Houghton Mifflin. *** 1/2

Dawkins, Richard. 1998. Unweaving the Rainbow. Houghton Mifflin. *** 1/2

Dawkins challenges the notion that understanding the physics behind a rainbow, for example, undermines its beauty. On the contrary, real science provides the same sense of wonder expressed by mystics and poets throughout history. Examples include Newton, prisms, and rainbows; DNA analysis; things we can rule out like astrology and perpetual motion; how to develop habits of mind to overcome superstition. Finally Dawkins speculates about why the human brain is so large, compared to other animals. Nice Sagan quote about the small-mindedness of religious world-views. (post)

Dennett, Daniel C.. 2013. Intuition Pumps and Other Tools for Thinking. Norton. ***

Notes here cover the opening portion of the book, listing a dozen general “tools,” some useful, some to avoid: Making mistakes; Reductio ab absurdum; Rapoport’s rules; Sturgeon’s Law; Occam’s Razor; Occam’s Broom; Using lay audiences as decoys; Jootsing; Goulding; “Surely”; Rhetorical questions; and Deepities. (notes, with comments about how science fiction is an intuition pump)

Deutsch, David. 1997. The Fabric of Reality: The Science of Parallel Universes—and Its Implications. Allen Lane. ****

Deutsch, David. 1997. The Fabric of Reality: The Science of Parallel Universes—and Its Implications. Allen Lane. ****

Not entirely about parallel universes, per se, the book describes how the increase of knowledge over the centuries has, paradoxically, made it easier to understand the universe, since the many earlier theories about various phenomena have merged into just a handful of “deep” theories — namely, quantum physics, epistemology, computation, and evolution — which comprise a “theory of everything” that can be understood. The book shows how these four ideas are analogs of each other, and how they do, via quantum mechanics, imply the existence of parallel universes, and even time travel of a sort. Provocative and at times abtruse, the author’s clear language nevertheless evokes a universe that is, if not unintelligible, in no way intuitive. (post)

Dole, Stephen H., & Asimov, Isaac. 1964. Planets for Man. Random House. ***

Dole, Stephen H., & Asimov, Isaac. 1964. Planets for Man. Random House. ***

I read this in 1970 and reread it again in 2021; it’s interesting to compare to the recent books by Adam Frank and Jamie Green. Asimov assesses the characteristics necessary to make a planet suitable for human habitation, e.g. suitable gravity, light, and so on, and then, in a process much like the famous Drake Equation, assesses the likelihoods of habitable planets around 14 of the nearest stars, finding the most likely system for such a planet to be Alpha Centauri A and B. Of course, our assessment of some of these factors has changed over the decades — especially the number of stars likely to have planets — but all the factors remain relevant. (post)

Frank, Adam. 2023. The Little Book of Aliens. Harper. ***

Frank, Adam. 2023. The Little Book of Aliens. Harper. ***

More pop-oriented than Frank’s previous book, this considers what ordinary people think about the topic of aliens. Usually, UFOs. He outlines the history of speculations about aliens (Drake’s equation, etc.), UFO sightings, SETI, and now UAPs. Then considers how we would find intelligent aliens, if they exist: by looking for biosignatures, and technosignatures, and what those mean. (Attempts to contact aliens via signals, as in Project Ozma, have been largely abandoned.) The substantial recent developments I hadn’t read about in other books concern the results of the orbiting observatory Kepler over the past two decades: it has found planets around virtually every star examined. This has great implications on the results of Drake’s equation. Further, the various systems of planets are never in the same arrangement as in ours, with small rocky planets close to the sun, big gas planets farther out. In passing, Frank notes that climate change may be an unavoidable consequence of developing technology; and how monobiome planets, all water or all desert, aren’t as implausble as I once thought. (post)

Frank, Adam. 2018. Light of the Stars: Alien Worlds and the Fate of the Earth. Norton. ***

Frank, Adam. 2018. Light of the Stars: Alien Worlds and the Fate of the Earth. Norton. ***

A consideration of our planet’s future and reconsidering the Drake equation, in light of the discovery of thousands of extra-solar planets and our understanding of how civilizations might become sustainable. With a revision of the ‘Kardashev Scale’ about planetary energy use, to a scale that considers how planets exist with their biosphere. (post)

Green, Jaime. 2023. The Possibility of Life: Science, Imagination, and Our Quest for Kinship in the Cosmos. Hanover Square Press. ** 1/2

Green, Jaime. 2023. The Possibility of Life: Science, Imagination, and Our Quest for Kinship in the Cosmos. Hanover Square Press. ** 1/2

Thematically similar to Adam Frank’s LITTLE BOOK, focusing on the nature of life in the universe within the context of cosmic history, from the origin of life, the planets, of animals and people, and possible contact with other intelligent life. This book is replete with references to science fiction, mostly TV and movies but also some novels and even short stories, by authors from Le Guin to Baxter to Butler to Lem to Chiang to Mieville. Like Frank she considers biosignatures and SETI. She admits she’s not concerned with odds; life might indeed be extremely rare, but thinking about it is what matters. In passing, I noted her point that life on Earth is so various that animals in Australia, for example, might as well be aliens compared to the rest of the world. (post)

Greene, Brian. 2020. Until the End of Time: Mind, Matter, and Our Search for Meaning in an Evolving Universe. Knopf. *****

Greene, Brian. 2020. Until the End of Time: Mind, Matter, and Our Search for Meaning in an Evolving Universe. Knopf. *****

A big picture book about the history of the cosmos, and humanity, with much familiar material but also two key themes of Greene’s own: the idea of nested stories to understand reality at various scales, and his idea of what kind of meaning we can deduce from our existence and the future of the universe. Early chapters concern entropy and evolution, and especially what the former actually means. Complexity including life, apparently contradicting the second law of thermodynamics, is possible because of what Greene calls the “entropic two-step,” essentially meaning the local complexity here will eventually drain back in the environment later. Then: the history since the big bang, “inflation” as the rare but inevitable consequence of repulsive gravity, the formation of the elements and of structures resulting in life. Darwinism at the molecular level. Life led to consciousness and the mind, and then to imagination, in particular to stories and why they are useful. Stories became religions with survival values and notions of the sacred. How beliefs arise, evolving to promote survival, not to understand reality. The roles of art in human society; artistic truth tells a higher-level story. The author fulfills the promise of the title by projecting the deep future: the fate of the sun and earth, black holes that sweep the galaxies clean. Thought might survive even the existence of matter, if it slows way down. Then the end of time and the disintegration of emptiness. Finally, meaning: There is no grand design or purpose; we exist while an infinite number of other possible people do not. Beyond that, perhaps our brains are not structured to answer the deep questions. We construct our own meaning. Perhaps, in the end, it is only story. (post 1; post 2; post 3; post 4; post 5)

Hawking, Stephen. 2018. Brief Answers to the Big Questions. Bantam. **

Hawking, Stephen. 2018. Brief Answers to the Big Questions. Bantam. **

Ten essays cobbled from Hawking’s speeches, interviews, and essays. Is there a God? Not in any traditional way. How did it all begin, is there other intelligent life, is time travel possible? With answers about Einstein, black holes, unified theories. Should we colonize space? Yes, to avoid catastrophe or a used up planet. Will AI outsmart us? It might, so we have to be intelligent about using it to our advantage. How to shape the future? Rely on science and technology, curiosity, imagination. (post)

Hawking, Stephen, & Mlodinow, Leonard. 2010. The Grand Design. Bantam. ** 1/2

Hawking, Stephen, & Mlodinow, Leonard. 2010. The Grand Design. Bantam. ** 1/2

Quick summary of the ideas of laws of nature, the basic forces of physics, “classical” themes of physics, superseded by quantum theories, and then the search for “grand unified theories.” Beginning the 1970s ideas included supersymmetry, string theory, and then “M-theory,” involving eleven space-time dimensions and 10^500 different universes. The “strong” anthropic principle is that because we exist, we must exist in a universe that allows for our existence, along with those infinitely many others with different physical laws. And how the “game of life” shows how complex states emerge quickly from simple rules. Because there is a law like gravity, the universe can and will create itself from nothing; the universe came into existence spontaneously. (post)

Kaku, Michio. 2021. The God Equation: The Quest for a Theory of Everything. Doubleday. ***

Kaku, Michio. 2021. The God Equation: The Quest for a Theory of Everything. Doubleday. ***

A succinct, crisp history of physics, from the Greeks to the present, and ending with, though not dwelling too much on, string theory, the author’s field of interest. The disingenuous title is likely the publisher’s. Kaku’s case for string theory is compelling, despite the admitted lack of evidence, in that the previously intractable problem of uniting gravity and quantum mechanics is solved via supersymmetry and multiple dimensions: as if the two theories only make sense when one is lifted (mathematically) into a different dimension. Kaku finds all this evidence of a cosmic designer, and that the ‘theory of everything’ will be the only possible universe because it’s the only theory that is mathematically consistent. (summary and comments)

Krauss, Lawrence M.. 2017. The Greatest Story Ever Told–So Far: Why Are We Here?. Atria. ***

Krauss, Lawrence M.. 2017. The Greatest Story Ever Told–So Far: Why Are We Here?. Atria. ***

This greatest story is a history of physics of the past few decades, accompanied by anecdotes about Richard Feynman, Sheldon Glashow, Steven Weinberg and others; with the theme of the discovery that the universe is not what meets the eye, and that the reality is greater than the myths and ignorance of past millennia. (post)

Lightman, Alan. 2021. Probable Impossibilities: Musings on Beginnings and Endings. Pantheon. ***

Lightman, Alan. 2021. Probable Impossibilities: Musings on Beginnings and Endings. Pantheon. ***

Collection of 17 essays. The title essay is about tracing your ancestors back through time, how every atom in your body was made in stars, and how we know this. The most striking essay, “Smile,” describes a man and woman passing each other along a lakeside, in terms of how many atoms and bits of light are exchanged in just a few moments. Other topics: how after death every atom of his body will eventually become parts of other people; how humans like disorder and asymmetry; how people are attracted to the idea of miracles despite no evidence for them, or for any other kind of reality; how the fraction of living material in the universe is fantastically small; and about the infinity of space and time and the idea of a vast number of universes, each spawning new ones. (post)

Lightman, Alan. 2014. The Accidental Universe. Pantheon. ***

Lightman, Alan. 2014. The Accidental Universe. Pantheon. ***

Seven essays about how the universe is not obviously what it appears to be, or is at odds with what humans might prefer. Topics include the history of science and a potential “theory of everything” (echoing Deutsch, perhaps); the human longing for permanence; science and faith (loosely construed); symmetries; how our conception of the size of the universe has grown; how scientists have become committed to the lawfulness of the universe; and how we know the Earth rotates even though we can’t feel it. (post)

Novella, Steven. 2018. The Skeptics’ Guide to the Universe: How to Know What’s Really Real in a World Increasingly Full of Fake. Grand Central. ***

Novella, Steven. 2018. The Skeptics’ Guide to the Universe: How to Know What’s Really Real in a World Increasingly Full of Fake. Grand Central. ***

Compiled by the producer and host of podcast of the same name (aka SGU), this is an encyclopedic guide to core concepts of skepticism (how our senses deceive ourselves; motivated reasoning; logical fallacies, cognitive biases, and heuristics); to examples of pseudoscience (p-hacking, conspiracy theories) and cautionary tales from history (clever Hans, quantum woo, pyramid schemes). Then examples of applying skepticism to topics like GMOs and claims of free energy. Media issues (fake news, false balance). How pseudoscience can kill (naturopathy; exorcism; denial of medical treatments). And a final section about being willing to change one’s mind when evidence compels you to. Don’t tell people what to think, but how. The book is uneven at times (with five co-authors), but exhaustive. (post)

Pinker, Steven. 2021. Rationality: What It Is, Why It Seems Scarce, Why It Matters. Viking. ****

Pinker, Steven. 2021. Rationality: What It Is, Why It Seems Scarce, Why It Matters. Viking. ****

Pinker discusses rationality as the ability to use knowledge to attain goals, yet admits problems when different people’s goals conflict (morality) or one’s goals today might conflict with later ones (wisdom). He explain situations in which it’s rational to be irrational, or at least powerless. The bulk of the book is an extensive guide of the tools of rationality: logic; probability; Bayesian reasoning; risk and reward; hits and false alarms; self and others (game theory); correlation and causation. Finally he tries to understand the current state of apparent irrationality, what with conspiracy theories and the persistence of supernatural beliefs. Not so much the effect of social media, he claims, but rather how our “cognitive facilities work well in some environments and for some purposes but go awry when applied at scale, in novel circumstances, or in the service of other goals.” Discussions thorough, thoughts sometimes profound, writing often sparkling, examples colorful. (post)

Pinker, Steven. 2018. Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress. Viking. *****

Pinker, Steven. 2018. Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress. Viking. *****

Notes forthcoming

Plait, Phil. 2002. Bad Astronomy: Misconceptions and Misuses Revealed, from Astrology to the Moon Landing “Hoax”. Wiley. ***

Plait, Phil. 2002. Bad Astronomy: Misconceptions and Misuses Revealed, from Astrology to the Moon Landing “Hoax”. Wiley. ***

Fun book by a blogger, skeptic, and TV personality who sets out to debunk commonly misunderstood ideas of astronomy and pseudo-science. Examples include what causes the seasons, what causes the moon’s phases, why stars twinkle, examples of bad astronomy in Hollywood pictures (sounds in space, spacecraft that bank like jet fighters, etc.), and debunking supposed hoaxes and pseudo-science (the moon-landing, Velikovsky, creationism, astrology). (post)

Pratchett, Terry, & Ian Stewart, Jack Cohen. 1999. The Science of Discworld. Ebury Press. ***

Pratchett, Terry, & Ian Stewart, Jack Cohen. 1999. The Science of Discworld. Ebury Press. ***

Discworld is a popular series of fantasy novels by Pratchett, but this book is not a rationalization of its universe, but rather an explanation of how its world, in which magic works and everything happens for a reason (a thesis dubbed “narrativium”), contrasts with our own, in which those two things are not true. Stewart and Cohen are popular science writers, and this book, in between fictional chapters by Pratchett, is a primer on current scientific thinking about the origins of the universe, physical theories of everything, the formation of our planet, the history of life on earth, the evolution of dinosaurs and ultimately of humans, told in a straightforward, insightful and occasionally cheeky, occasionally profound, manner. Another running concept is how most explanations given to children have to be simple: “lies to children”. (post)

Rovelli, Carlo. 2016. Seven Brief Lessons on Physics. Riverhead. ***

Rovelli, Carlo. 2016. Seven Brief Lessons on Physics. Riverhead. ***

Slender book compiled from the author’s newspaper column intended for readers who know nothing about science. It’s noteworthy for the author’s ponderings on the native caution of scientists, and how humanity’s place in the universe is very small, despite our previous misconceptions (echoing Sagan’s “demotions” in PALE BLUE DOT). His conclusion is pessimistic: that our species will not last long. But it has happened before, with cousin species, and individual human cultures, having disappeared. But as our knowledge of the world continues to grow, we can perceive “the mystery and the beauty of the world.” (post)

Sagan, Carl. 2006. The Varieties of Scientific Experience: A Personal View of the Search for God. The Penguin Press. ***

Sagan, Carl. 2006. The Varieties of Scientific Experience: A Personal View of the Search for God. The Penguin Press. ***

A posthumously published collection of nine lectures Sagan presented in 1985, here edited by Ann Druyan. Despite his invitation to speak of “natural theology,” Sagan repeatedly deflects ideas that theological knowledge can be established by reason or experiment; he politely mentions such notions and then wonders if we should not perhaps seriously consider that there might be better explanations. Topics include the awe of looking into the night sky (and how the vastness of the universe has been taken into account by no Western religions), and considers science to be “informed worship.” He anticipates human mental biases by reflecting on how humans project our own feelings and privilege to think ourselves the center of the universe. The history of science has done away with divine microintervention in earthly affairs; objections to evolution are misguided. He speculates on beings more intelligent (rather than powerful) than us. He reflects on the willingness to believe in ancient astronauts and UFOs, and sees similar lack of scrutiny in believing supernatural miracles. And he reviews so-called proofs of God, beginning with 11th century proofs of the Hindu God (“these arguments are not always highly successful”) and compares modern Western counterparts. Why didn’t God set things right in the first place? Why no clear evidence of his existence? He traces predispositions toward religious belief to the emotions of our primitive ancestors, and how children grow up in a world of giants. And he challenges the supposed wisdom of the ancients with the reality of our changing world and the threat of nuclear war. Finally: the search for meaning is two-pronged: to understand the universe, and to understand ourselves. History is a battle of inadequate myths. It would help to have another planet, another intelligence, to understand ourselves better. (post)

Sagan, Carl. 1996. The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark. Random House. *****

Sagan, Carl. 1996. The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark. Random House. *****

Sagan takes on pseudo-science by showing how science is the methodology for determining what’s real and what’s bunk, discussing psychological reasons for why people are attracted to pseudo-science (and religion) and put off by real science, and the ways the ideals of science and democracy align. Memorable chapters concern Sagan’s “fine art of baloney detection” (e.g. reproduced here), his “dragon in my garage” metaphor about supernatural claims that lack all evidence, and a strong discussion of the methods of values of science. A running theme: science is a balancing act between being open to wonder, and being skeptical when drawing conclusions; followers of pseudoscience are open to wonder but lack all skepticism. The book is a tad dated in its focus on pseudo-scientific issues of the ’90s, e.g. UFOs and alien abductions, but its principles remain today as relevant as ever. (post)

Sagan, Carl. 1994. Pale Blue Dot. Random. ****

Sagan, Carl. 1994. Pale Blue Dot. Random. ****

This “sequel” to 1980’s Cosmos updates that book’s account of humanity’s exploration of the solar system and speculates on how such exploration will proceed into the far future. There are two big highlights: first Sagan’s account of the famous “pale blue dot” photo of Earth taken from the edge of the solar system by Voyager 1, and his moving description of Earth’s place in the vast cosmos; second, a catalog of “demotions,” ways in which human presumptions of being at the center of creation have been undermined, over and over. By the end Sagan contemplates various fates of humanity, and how our ultimate survival may depend on leaving the Earth and exploring the Milky way. (summary part 1; part 2)

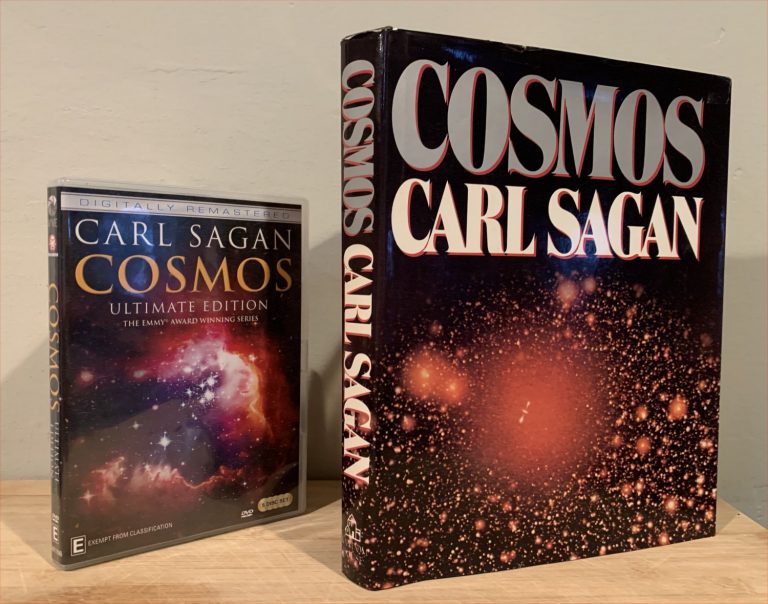

Sagan, Carl. 1980. Cosmos. Random House. *****

Sagan, Carl. 1980. Cosmos. Random House. *****

Sagan’s famous book companion to his 1980 13-part TV series was the best-selling science book of all time, at its time. It’s about what we know about the cosmos — from the planets, to the stars, to the galaxies, to speculations of other intelligences — with explanations of *how* we know these things, many envisioned in historical re-enactments. And concerns about the future of our planet, given environmental threats apparent even back in 1980. (post)

- Sagan, Carl. 1979. Broca’s Brain. Random. –

Notes forthcoming

Sagan, Carl. 1975. Other Worlds. Bantam. **

Sagan, Carl. 1975. Other Worlds. Bantam. **

A thin paperback “produced by Jerome Agel” containing photos, cartoons, graphics, and quotes, along with passages by Sagan about the search for extraterrestrial intelligence; pseudoscience from UFO sightings, astrology, and Velikovsky; and the connection of humans to life on earth, the potential of exobiology, and the discoveries humanity is on the verge of making. (post)

Sagan, Carl. 1973. The Cosmic Connection: An Extraterrestrial Perspective. Doubleday/Anchor Press. *** 1/2

Sagan, Carl. 1973. The Cosmic Connection: An Extraterrestrial Perspective. Doubleday/Anchor Press. *** 1/2

One of the first nonfiction books I read, and foundational in my discovery of astronomy and the perspective of how humanity lives in a vast universe greater than any parochial or religious view. Parts of this, about then-current discoveries in the solar system, are dated, but other chapters, on the 5-billion-year history of Earth, and the motivations for space exploration, are inspiring to this day. Other chapters, about dolphins, seem asides, but later chapters about contact with extraterrestrial life, and classifications of cosmic civilizations, and mankind’s place in a universe of ‘starfolk’, are also as inspiring as ever. (post)

Snow, C. P.. 2013. The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution. Martino Fine. ****

Snow, C. P.. 2013. The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution. Martino Fine. ****

Two essays. The first is a famous 1959 essay about the divide between the scientific community and the literary ‘intellectual’ community that considers it unimportant or even in bad taste to know much about science. One of the most influential and cited essays of the 20th century. The second is about how industrialized nations are getting richer and how poor nations have noticed and will turn to Russia if the West doesn’t help. [summary here also discusses the development in the past 20 years of a ‘third culture’ exemplified by EO Wilson’s Consilience and the “Big History” movement, plus a passage from Michael Benson’s book about 2001 about how science fiction is a blending of art and science.]

Strevens, Michael. 2020. The Knowledge Machine: How Irrationality Created Modern Science. Liveright. ***

Strevens, Michael. 2020. The Knowledge Machine: How Irrationality Created Modern Science. Liveright. ***

This book has an attractively non-intuitive premise: why would science, supposedly the epitome of rationality, have been created by irrationality? Because scientists, as humans, are as subject to psychological biases, like motivated thinking, as any of us. Strevens’ key is that the irrationality of scientists is necessary for the advancement of science, lest science sink into a torpid set of unchallenged conventional wisdoms. His second big idea is that science took so long to emerge (in the West) because the Church suppressed scientific thinking, until the Thirty Years War in the mid-17th century that re-aligned Europe into cultures aligned by nationalism, not religion. And his third claim is that he is skeptical of any eventual unification of the humanities and science (c.f. Wilson and others). He contrasts the positions of Kuhn and Popper and concludes neither one was quite right. Throughout, Strevens insists on the “iron rule of explanation,” which is that “all scientific arguments be settled by empirical testing.” And so he rejects scientific theories based on “beauty” or aesthetic consideration — e.g. string theory. (post)

Thorne, Kip. 2014. The Science of Interstellar. Norton. ** 1/2

Thorne, Kip. 2014. The Science of Interstellar. Norton. ** 1/2

Director Christopher Nolan created the scenario for the film and then went to Thorne for scientific justification, with the latter pushing back in some cases. Along the way Thorne glosses on the major developments of 20th and 21st century physics — relativity, warped time and space, black holes, wormholes, higher dimensions, our universe as a ‘brane’ within a higher-dimensional ‘bulk’, how gravitational ‘anomalies’ lead to advances (Einstein, dark matter, dark energy), singularities (not just one type but three), the tesseract, and whether time travel is possible via wormholes. (post)

Tyson, Neil deGrasse. 2022. Starry Messenger: Cosmic Perspectives on Civilization. Henry Holt. *** 1/2

Tyson, Neil deGrasse. 2022. Starry Messenger: Cosmic Perspectives on Civilization. Henry Holt. *** 1/2

Somewhat like Sagan’s THE COSMIC CONNECTION, Tyson brings a cosmic sensibility to current issues, including vegetarianism, race, gender, disabilities, tribal forces in politics, the legal system and tropes about conservatives and liberals (how their differences reflect tribal forces within us, echoing Wallach and Gregg) with examples of nuclear families, science denial, how the two political parties once held opposite positions, and government social programs. He’s willing to challenge verities and explain why they aren’t actually true. Science informs everything: “Do whatever it takes to avoid fooling yourself into believing something is true when it is false, or that something is false when it is true.” There’s a terrific passage about how black racists might demeaningly depict whites. He discusses his idea of a “Rationalia” nation, and how it was denounced; and he contrasts the idea of the soul, given our chemical reality. As one would expect, Tyson comes down on the sides of reason and logic, recognizes complex realities rather than simple solutions or simple dichotomies, and above all advocates a respect and understanding of the universe around us as the proper foundation for genuine awe. (post)

Tyson, Neil deGrasse. 2019. Letters from an Astrophysicist. Norton. ** 1/2

Tyson, Neil deGrasse. 2019. Letters from an Astrophysicist. Norton. ** 1/2

A collection of letters, and Tyson’s responses, in his role as director of the Hayden Planetarium. Throughout Tyson is polite and restrained where he could be confrontational. Topics include aliens, UFOs, pseudo-scientific claims; hate mail and science denial; life and death, tragedy, and belief; his school days, parenting, responses to a flat earther and accusations that liberals are anti-American. And a farewell letter to his father upon his death. (post)

Tyson, Neil deGrasse. 2017. Astrophysics for People in a Hurray. Norton. **

Tyson, Neil deGrasse. 2017. Astrophysics for People in a Hurray. Norton. **

Collection of magazines essays about the earliest moments of the universe, the creation of the elements, the discovery of physical laws, dark matter, dark energy, and other topics. Tyson is no Carl Sagan, or Ann Druyan, but these essays are pleasant introductions to cosmic topics, with reflections of living cosmically. (post)

Weinberg, Steven. 2015. To Explain the World: The Discovery of Modern Science. Harper. *** 1/2

Weinberg, Steven. 2015. To Explain the World: The Discovery of Modern Science. Harper. *** 1/2

The Nobel physicist provides a history of science and a history of the idea of science, from the Greeks to Newton. The key theme is that “The progress of science has been largely a matter of discovering what questions should be asked.” It took centuries to realize that it was never “fruitful to ask what motions are natural, or what is the purpose of this or that physical phenomenon.” The ideas of the Greeks — earth, air, fire, water; ‘atoms’ — were poetical, never tested. There wasn’t much distinction between science and philosophy for thousands of years, and there was much rationalizing with religion (e.g. Aquinas). The breakthroughs came in the 15th and 16th centuries with Copernicus, Tycho, Kepler, and Galileo. The Church, of course, refused to look through Galileo’s telescope and banned his books. The scientific revolution climaxed with Newton, with his insights summarized in his three ‘laws.’ [And in retrospect, we can understand early attitudes toward science as reflecting biases of the human mind– assumptions, never tested, that the universe must be something beautiful or perfect by human standards.] (post)

Wilczek, Frank. 2021. Fundamentals: Ten Keys to Reality. Penguin Press. ***

Wilczek, Frank. 2021. Fundamentals: Ten Keys to Reality. Penguin Press. ***

The Nobel Prize-winning physicist describes ten “keys” to understanding the universe, implied as alternatives to traditional religious fundamentalism. These include things like space and time, the sparseness of basic building blocks and fundamental forces, the immensity of matter and energy, and properties like complexity and complementarity. This last concept, paralleling Sean Carroll’s “poetic naturalism”, includes emergent properties and levels of complexity as escapes from the trap of material reductionism. There’s a good quote about how understanding these concepts helps us rule out intuitively attractive ideas of astrology, ESP, magical thinking, and other examples of action-at-a-distance, that most people adopt as children. (post)

Wilson, Edward O.. 1998. Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge. Knopf. *****

Wilson, Edward O.. 1998. Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge. Knopf. *****

Likely Wilson’s magnus opus, this is his attempt to describe a worldview that unifies all knowledge, especially between the sciences and the humanities, leaving religion behind (as he did as a boy) and applying scientific principles and insights even to areas where this viewpoint is resented. He addresses the great branches of knowledge, and reflects how the Enlightenment was constrained by the deism of its leaders. How science works: “the most effective way of learning about the real world ever conceived.” How philosophy has been hobbled by “ignorance of how the brain works”. How science is challenged by the complexity of systems, with ideas of emergence avoiding the perils of reductionism. His chapter 6 on the mind corresponds to Pinker’s entire book on the subject: the mind is the brain, it evolved for survival and not perception of the real world, and so on. He describes how culture emerges from human nature, and how human nature entails regularities like kin selection and altruism. Then, as Pinker does later, applies these understanding to particular aspects of human culture, especially in the social sciences: the arts and their interpretation, ethics and religion. Finally he asks, To what end? What is humanity’s future? The key questions are: what we are, where do we come from, and how shall we decide where to go. Neither theology nor philosophy has answered these. Our challenges include our potential dependence on prosthetic devices, and our damage to the natural world. He comes down on “existential conservatism”: “The legacy of the Enlightenment is the belief that entirely on our own we can know, and in knowing, understand, and in understanding, choose wisely.” A big book that’s in a sense about everything. Wilson is one of the most graceful and deeply insightful science writers ever. The post here is the 11th, and it links to the earlier 10. (post)