Subtitled “How False Beliefs Spread”(Yale University Press, 2019, 266pp, including 80pp of notes, bibliography, acknowledgements, and index)

This is an interesting enough book that wasn’t quite what I was expecting. It seems right up my alley: why do so many people believe things that are not true? Sure social media is involved (with their conspiracy theorists and chaos agents), and we understand that most people know only what they hear from social media or glean from casually interacting with their friends and neighbors. Further, no matter how ambitious or well-intentioned one is, no one can acquire first-hand knowledge about everything, so to some extent we rely on experts, or at least on the conclusions of those who have studied matters more deeply than we are able to. Even further, as I’ve discussed, most people live their mundane lives without any great concern about whether what they believe about matters outside their immediate concern are true or not; they don’t care, and it doesn’t actually matter toward living a good life.

These topics do come up in this book, some only in passing. A key idea I didn’t see was how people, living in real or virtual social bubbles, cannot change their minds for fear of being socially ostracized. (Though that turned up in the next book I read!) On the other hand, there are some new perspectives here that make it a useful supplement to similar books I’ve read. Let me summarize these here at the top:

- Perhaps the key point here is that people form beliefs based on information from others, and acquiring false beliefs isn’t simply a matter of psychology or intelligence; various social factors are essential to spreading beliefs, including false beliefs;

- A running thread is how even scientists can form and perpetuate false beliefs, despite their particular devoting to identifying truth, given that scientists are subject to social factors as well. Examples include the ‘discovery’ of a 14th century Indian tree; debates over the ozone layer and acid rain, the cause of ulcers. Scientists and others converge on beliefs via social networks that the book illustrates with network diagrams like this one:

- Controversy can emerge when these networks, with inputs from scientists, propagandists, journalists, and policy makers, reach local conclusions without interacting with each other. But more than many people realize, these networks also go wrong when propagandists (typically for big business) work to undermine the conclusions of scientiswts, by manipulating evidence, or selectively distributing it. Not everyone is actually after the truth; the ‘marketplace of ideas’ is a fiction.

- Among remedies for these problems, the authors suggest a re-imagining of democracy, given that in free elections most voters have no idea what they’re talking about. This is the most provocative idea in the book, and details about it are at the end of the summary here.

Intro: The Vegetable Lamb of Tartary, p1

The book opens with an anecdote about the 14th century discovery of an Indian tree that bore fruit containing tiny little lambs, complete with flesh and blood. Other writers made similar reports, and naturalists took them as fact until they were debunked in 1683. How could this happen? Could it happen now? What are today’s Vegetable Lambs?

In 2016, a post claiming that the Pope endorsed Trump (from a dicey news source) got nearly a million shares or likes. Another post wondering why Hillary was seen as corrupt (from WaPo), fewer times. The former was fake. Similar trend about similar stories. ETF News (ending the fed) was the source of many of the top twenty most shared posts. None of its stories was true. And were often lifted from other fake news websites. Such fake news drove Trump’s election and Brexit. Can democracy survive the age of fake news?

This book is about truth and knowledge, science and evidence, but also about false beliefs. How do they form and spread? Beliefs about the world matter. About health matters, about how to run a society. The real world pushes back against false beliefs. Why do people acquire them? Psychology or intelligence is not the point; people form beliefs based on information from others. We only know what other people tell us. [[ this is the key point ]] Including scientific beliefs. So how do we know whether to trust what people tell us? We don’t want to fall for false beliefs. Perhaps believing some falsehoods is the price we pay for using our most powerful tools for learning truths, 9.7.

Our age of misinformation includes propaganda, written to promote particular views. Both political, and industrial. Example of tobacco companies. Still, why is misinformation widely accepted? This book argues that social factors are essential to spreading beliefs, including false beliefs. [[ and religion of course; community is much more important than seeking out objective sources. ]] Many examples of how this happens come from science. Because they’re the ones doing their best to learn about the world, yet still can persist in false beliefs. The methods of science include computer simulations and mathematical models. Considering these will change our conception of ourselves – the Western idea that humans are essentially rational (14.3). But this picture is distorted. Rational agents can form groups that are not rational. A disconnection between individual and group level rationality. We evolved to thrive in our evolutionary environments. We’re social animals. Social conditions matter as much as individual psychology.

Recall Dr. Strangelove and its ‘precious bodily fluids’ concern about fluoridation. Today such fringe beliefs are common, even in government. We’re becoming less tied to truth. How can we fix this? A key argument is our political situation depends on understanding networks of social interaction. From face-to-face to online. We trim our contacts only to those who share our views and biases — echo chambers. One conclusion is that propaganda works even when information is not fake, i.e., when real information is reported in misleading ways, 17. Journalists trying to be ‘fair’ by presenting both sides can deeply mislead the public. Some obvious efforts are unlikely to succeed. Those that might succeed would be radical, 18t, e.g. to limit the distribution of fake news. [[ exactly what Facebook has just given up trying to do ]] It is the abundance of information, shared in novel social contexts, that underlies the problems we face, 18.8.

One, What Is Truth?, p19

In 1985 three scientists discovered the ozone levels over Antarctica had dropped. Yet a satellite saw no change. M/w two chemists at UC Irvine discovered that the ozone depletion could come from CFCs. More studies. In 1977 the FDA banned CFCs. Yet ozone was being depleted faster than everyone thought possible. Turned out the satellite had seen it, but the data was thrown out as outliers, a standard method of separating signal from noise. The data was processed assuming levels would never read that low. Various other factors were discovered to explain it. By the late ‘80s cuts to CFCs were agreed to.

Recall Pilate asking “what is truth”? Such ideas go way back. It’s also used by politicians to undermine their critics. Bush’s own reality, and Trump’s alternative facts. Johnson’s lies about Vietnam. So the problem is, can we ever really know anything? In the 70s the chemical industry pushed back against regulations, emphasizing uncertainty, wanting delays, no matter how much evidence there was. Example of DuPont. Like Hume, and the Greeks: how much can you infer? Hume said no; this was the problem of induction. Science might always be wrong. We can never be absolutely certain about anything. And science has been wrong: about bad air or “miasma” [[ but those were not scientists in the modern sense. ]] That the earth is the center of everything. Newton giving way to relatively. [[ again, these were shifts in scale and not a matter of having been wrong in the same way; the authors risk oversimplifying their these. ]] So were critics like DuPont correct? No; we can be more or less confident about many things. Given risks, absolute certainty is irrelevant. We can’t wait for absolute certainty. Some of those old theories worked just fine in their contexts. Beliefs come in degrees. We can adjust degrees using Bayes’ rule, for example. We update our degrees of belief based on evidence. (The answer about DuPont and tobacco companies is to consider who benefits.)

Some accused the scientists proposing the CFC ban of having political motivations. The KGB! 31m. Or the charge was that scientists are influenced by culture, politics, etc. Kuhn, 1962, his famous notion of normal science and paradigm shifts, that evidence alone wouldn’t lead to scientific theories, that science was the product of while male Europeans, whose cultures had histories of atrocities around the world. Such ‘science studies’ continued in the 1970s and 80s. So yes, scientists might have certain biases; but they do not undermine evidence and arguments.

There is another way politics and science can mix. Recall a volcano in Iceland in 1783, resulting in acid rain, which was realized in 1859 to be a product of industrialization. It became a concern in 1974, and realized as far more widespread than previously thought. Especially from one country to the next. The science was firm by the early ‘80s. Many nations imposed restrictions on power-plant emissions. But not the US, under Reagan, who tried to prevent any such action — up to tampering with the scientific record. The White House hand-picked members of an advisory committee. One pick rejected the consensus and insisted that nothing be done. And so on. (Authors refer for background to that Oreskes/Conway book that I haven’t read.) And so nothing was done about acid rain until Reagan left the White House. [[ this is all happening again, with climate change, under Trump. ]]

By the 90s perceptions grew among scientists that humanities were trying to undermine it, and they began pushing back. Thus the ‘science wars.’ 1994 book Higher Superstition argued that many humanists writing on science were pseudoscientific poseurs. And so on.

The idea here is beliefs that are ‘true’ serve as guidelines for making successful choices in the future. Most of us are not in a position to evaluate data ourselves; we have little choice but to trust the scientists, whose views are informed by the evidence. The evidence remains even if science is part of culture and politics. The threat to science is from those who would manipulate scientific knowledge for their own interests.

[[ note this chapter for its examples of conservative/Republican opposition to scientific conclusions if they don’t fit ideology, or are inconvenient for business or industry. ]]

Two, Polarization and Conformity, p46

About mercury, known to be poisonous, and how about in 2000 contaminated fish were realized to cause mercury poisoning. Jane Hightower. Real discoveries commonly involve many people, not lone geniuses. 48m. In this case, there were skeptics about the source of the poisoning as mercury. Regulations were already in place. Eventually her work led officials to update guidelines.

In 1953 Francis Crick announced that he and James Watson had discovered the ‘secret of life.’ They had built models with glorified tinker toys. Model building is ubiquitous in the sciences. Bayes’ rule is a kind of mathematical model. But how does a group come to consensus? A model for this was introduced in 1998 by Bala and Goyal. In this model there’s a group of simple agents. Each agent makes a decision about action to solve a problem, and these are tracked. A problem is that evidence is seldom dependable; many factors can affect it. This is modeled with computer simulations, p56. Each node (scientist) has a level of certainty between 0 and 1. Through interactions they updated their credences, p58. Eventually a consensus is reached, if not always a true belief. The question is, under what circumstances do they converge to a false belief?

Consider ulcers. It took decades to determine that they are caused by bacteria, though it was suspected back in 1874. It wasn’t the only idea. For a while the bacteria model failed the evidence; stomach acid was favored. So what happened? Sharing evidence led to one conclusion or another. Example p62. Misleading evidence can lead the entire network astray. It would have been better *not* to share such evidence. So sometimes it’s better not to collaborate. This is called the Zollman effect. Diversity of beliefs can be maintained by limiting communications.

About Polly Murray in 1975 suffering fatigue, etc., a condition eventually called Lyme disease. But over the decades controversy emerged over chronic Lyme disease, that perhaps it was a combination of other diseases, and whether antibiotics could treat it. Threats were made against the scientists who originally diagnosed it. At issue was how much insurance companies would pay. In 2017 there was a shooting at a Republican baseball game by a left-wing extremist. Two months later was Charlottesville, led by right-wing extremists. These were examples of what came to be called polarization. The Lyme disease controversy was about polarization among scientists. Scientists are people too. But how did they get so polarized? Perhaps it’s about trust of other colleagues. This affects the model, by modifying how Bayes’ law works. It can radically change the outcomes. You end up with two groups who don’t listen to each other. And no amount of evidence will convince either side. …

Polarization has been studied in many disciplines. We see confirmation bias and motivated reasoning in many examples, some over moral issues, some over scientific facts. Distrust of people shouldn’t interfere with assessing actual evidence. In 1846 Semmelweis studied differing death rates in two hospitals. He discovered that doctors had conducted autopsies before treating patients. He had them wash their hands in between. Some physicians resented his conclusions. But his advice worked, though many rejected it for decades. The evidence was strong; why was it rejected?

2017, we had Donald Trump and claims about the size of his inauguration crowd. The White House denied the facts. Studies identified a phenomenon called conformity bias. Example of Solomon Asch in 1951. P80. People don’t like to disagree, and sometimes they trust the judgments of others over their own. Similar with audience polls on game shows, of the stock market, in which some people follow the herd. Information cascades. The critics of Semmelweis conformed to each other. Trump supporters conformed to the lie about his crowd size.

And not all people care about truth. Some care more about agreeing with other people. Some will deny their beliefs and the evidence of their senses to fit with those around them. Even scientists, if they only care about matching each other, will as likely settle on a bad consensus. But most people care about both. Some of the scientists may not have tried handwashing just to avoid censure from their peers. Or, when two groups might be weakly connected to one another, e.g. in two countries, they may not share information. Each conforms only within itself. P87. Or where everyone’s belief is correct but worse actions emerge anyway, p88. They conform instead. This ‘desire to conform’ is the main variable in these models. Especially when the cost of a false belief is low, as with the Vegetable Lamb. Or when the victims of not washing hands were only poor unknowns. A cash incentive might overcome the conformity bias. Conformity is a social signal, telling people which group you belong to. Examples of evolution, GMOs, organic foods. Conformity to different groups can look a lot like polarization.

So social networks are our best sources of new evidence and beliefs. But they can have negative social effects. But even this assumes that the goal is establishing truth. In the real world, this is often a bad assumption.

Three, The Evangelization of Peoples, p93

In 1952 Reader’s Digest published clear evidence of the link between smoking and lung cancer. Further evidence arrived. It was all bad press for the industry. Sales dropped. So the tobacco industry came up with a ‘strategy’ to use science against science –to cast doubts, emphasize uncertainty. The created propaganda, beginning in 1954. It promoted certain research, but only to contradict the consensus. Sales rose again; the strategy worked.

Propaganda was exactly what the Church did beginning in the 17th century to spread the faith. Modern propaganda began in the US during WWI. [[ Annalee Newitz’ book, not yet written up here, covers this period. ]] 97b. To sell Americans on the war, often lying. These techniques were used in the 1920s to manipulate public opinion, e.g. to depict women smoking as a sign of their liberation. With an example of an Easter Parade [[ like in the famous movie ]] which wealthy women walked down the street smoking. It’s gone on for years; thus we believe that fat is unhealthy (while sugar is not), against legalizing marijuana (but not alcohol), that opiates are not addiction, that gun owners are safer than non-owners. Edward Bernays [[ see Newitz ]] thought these techniques would be for the benefit of society. But his books sound like conspiracies. It undermines the idea that a democratic society can exist.

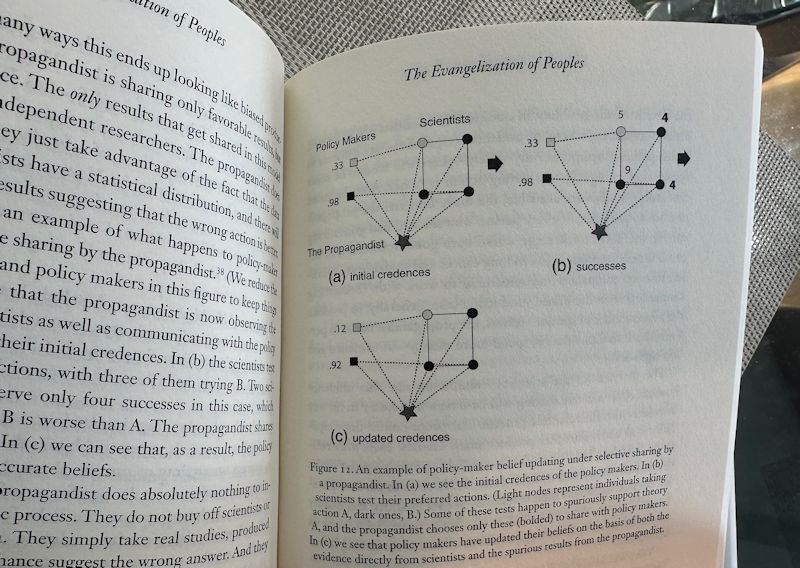

The tobacco strategy delayed the surgeon general warning about smoking until 1964. Later studies showed that smokers and nonsmokers tended to cluster in groups; the ideas of the previous chapter apply. Example of a networks with policy makers and scientists, and then with propagandists added. The propagandists use science to fight science, by funding their own ‘research’. If they didn’t like the results, those studies weren’t published. They knew since the early 1950s. Add this suppression to the model. Now policy makers are more likely to choose the wrong action. This is all due to selective publishing of results. This happens in regular science, when results are not exciting enough. Another technique propagandists use is to break data down into several studies with few data points, p109, and share only those with the best outcomes.

Another is ‘selective sharing’, promoting real research that conforms with the propagandists’ interests. Examples. They take advantage of the public’s misunderstanding the probabilistic nature of science. Or, they would overplay scientists’ own cautions about their results. Another model, p113. A tug of war goes on between the scientists and the propagandists, for influence over the policy makers. It’s actually better to fund fewer groups that gather more data each. Similar rationale explains the replication crisis; studies with spurious novel effects are easier to get published than those showing no effects. …

In 2003 the AMA voted on mercury levels in fish. But the vote was derailed by a claim that mercury was not harmful after all. Jane Hightower traced it to a report funded by the coal, tuna, and fisheries industries. Who claimed their funding had no effect on the results. But such funding would have an influence on the scientists. Details. Another example came with a study about arrhythmia and heart attacks. But the drugs to prevent arrhythmia had the opposite effect. The industry funded those studies that supported the position it wanted. Another example is a propagandist sharing biased research with real scientists.

Those are about manipulation of evidence, by selectively distributing it. But propagandists can also play on our emotions, as advertising does. Marlboro Man. Examples in Mad Men. Authority figures like physicians and the clergy can influence consumers. So the idea of physicians recommending an American breakfast of bacon and eggs. Similarly, some cigarettes were promoted as healthier than others. Neither based on any evidence. Other cases deliberately undermine the authority of scientists or doctors, e.g. via accusations of bias or illegitimacy.

Roger Revelle was an oceanographer who published a study about the rate at which carbon dioxide is absorbed into the ocean. It was already known that CO2 in the atmosphere was correlated to global temperature. But it wasn’t considered a problem in 1957. Revelle & Suess’ study projected that warming would get worse as emissions continued. In 1965 Revelle met Al Gore, who in 1992 published his book (An Inconvenient Truth). Critics went after Revelle. Fred Singer, the guy who quashed action on acid rain, got Revelle to agree to be a coauthor of a paper saying evidence was too uncertain for action at this time. A claim that Revelle himself did not write, and he died soon after, so Singer was left to claim his full endorsement of the msg. His name on the paper was used to undermine Gore’s agenda. And his reputation. NO evidence was involved; just a misleading conclusion from one article. This is just one example of industrial propaganda in science. Used in the Tobacco Strategy as well, with the NIPCC, an anti-IPCC whose strategy was to publish opposite conclusions with the recommendation to do nothing. …

Of course trust involves many factors, just as in the real world people are dealing with more than one problem at a time. Example network. Example of a Lady Montagu, born 1689. She discovered ‘variolation’ in Turkey and tried to bring it to Britain, to fight smallpox. She got it accepted by showing that the Princess of Wales was willing to do it. The same social pressure can work in reverse, of course. Example of case in Minnesota where anti-vaxxers triggered a measles outbreak.

This section has been about propaganda, mostly working within scientific groups…

Four, The Social Network, p147

Recall the guy, in 2016, who shot up the pizzeria in Washington DC. It followed social media posts alleging an international child sex ring. Then spread in social media. Details. Previous chapters were mostly about science, where we assume most actors *want* to know the truth about the world. But in our daily lives we are all trying to figure stuff out about the world. Applying the earlier models to ordinary people tells us a lot about today’s politics. Climate change, healthcare, nuclear treaties, trade agreements, gun regulation, tax rates. People have very different sources for news. Do we blame those who disagree with us on their ignorance? What are the social factors behind ‘fake news’?

Fake news goes back to pamphlets published around the American Revolution, attacking opponents. A warship exploded in Havana in 1898; the Spanish American War followed. Other examples: Herschel finding life on the moon. Poe on a trans-Atlantic balloon journey. But it’s all gotten worse in the lead up to the 2016 Brexit and presidential votes. What’s changed is the reach of news publications, with the internet. Yet why do so many believe outrageous stories? Some share as jokes. Others really believe. Surveys. An industry maxim is that news publishes what’s unusual. But the novelty bias can be problematic. Sharing limited results can cause the public to converge on false beliefs. Another mechanism is the ‘fairness’ doctrine about offering ‘both sides’ of a controversy. A useful tool for propagandists, e.g. for the tobacco industry. But promoting only the consensus can be wrong too, as claims about Saddam Hussein and his weapons. So how do journalists tell the difference? Well, they shouldn’t judge scientific disagreements; but they should investigate and question facts upon which policies are based. Thus they need to vet their sources. This is where institutions play a role.

In 2016 a man named Seth Rich was shot by police at 4am while walking home from a bar. Conspiracies began that he was killed by the Clintons to cover up election fraud. Charges against the Clintons were made in the 1990s. The 2016 story grew, involving Russian hackers of DNC computers. Wikileaks released thousands of Clinton emails. Julian Assange implied that Seth Rich was involved, with no evidence. Fox News and others made further allegations. They fabricated it. Some, like Sean Hannity, kept repeating the story anyway. At least Fox, like CNN and MSNBC, retracted a story found to be false; other right-wing sites didn’t, and never do. A problem is that such fake news items set an agenda for covering an event accused of being part of a conspiracy. To avoid this, leave fact checking to fact-checkers, the authors suggest.

There’s overwhelming evidence that Russians attempted to interfere in the 2016 US election. Consider what their motive was for doing so. Why release stolen emails? Perhaps to disrupt the Democratic Party. To create social division. Details. Facebook groups. Affinity groups. Establish shared interests or beliefs first.

Should social media sites identify fake news and stop it? Authors says yes, 173b. But how would a filter distinguish real stories from fake ones? Algorithms aren’t enough. The targets aren’t fixed. Spreaders of fake news will outwit the detectors. As in an arms race. We just have to keep trying.

Some possible interventions are… Make issues local, and less easily manipulable. Budget earmarks might actually be useful for local engagement. Change how information is shared in social media. 177. Trust might be engaged by finding spokespeople with shared values. Especially about minority opinions; mavericks.

We should stop thinking that the ‘marketplace of ideas’ will sort fact from fiction. The marketplace is a fiction. Free speech is an exercise of power. So scientific communities should adopt norms of publication; consider inherent risks when they publish. Minimize playing into the hands of propagandists. Combine results. Abandon industry funding of research. Journalists must hold themselves to different standards when writing about science and expert opinion, rather than attempting some kind of ‘fairness’. Wikipedia does a ‘proper weighting’ of competing views. Use the framework that limits certain industries, like tobacco and pharmaceuticals, and extend it to other efforts to spread misinformation, e.g. Brietbart News and Infowars. Europe is farther ahead than the US in this. Volunteers doing something like PolitiFact. [[ this is exactly what conservatives consider censorship, of course. ]] Free speech doesn’t include defaming individuals. Like labels on boxes of food.

Most controversial of all: reimagine democracy. Note two books by Philip Kitcher. The idea of what it means to have a democratic society that is responsive to fact. The problem is that most people who vote have no idea what they are talking about. It amounts to ‘vulgar democracy.’ Their beliefs are manipulated. Individual experts also cannot make decisions; they don’t know what matters to ordinary people affected by policies based on that science. Rather a “well-ordered science”. This may be utopian… 185b. We need to begin reinventing out institutions to work toward this goal.

\\

This last is the key interesting idea in the book, so I’ll quote a bit their comments from a book by Philip Kitcher, page 185:

Kitcher proposes a “well-ordered science” meant to navigate between vulgar democracy and technocracy in a way that rises to the ideas of democracy. Well-ordered science is the science we would have if decisions about research priorities, methodological protocols, and ethical constraints on science were made via considered and informed deliberation among ideal and representative citizens able to adequately communicate and understand both the relevant science and their own preferences, values, and priorities. But as Kitcher is the first to admit, there is a strong dose of utopianism here: well-ordered science is what we get in an ideal society, free of the corrupting forces of self-interest, ignorance, and manipulation. The world we live in is far from this ideal. …

Of course, replacing [our current] system with well-ordered science is beyond impractical. What we need to do instead is to recognize how badly our current institutions fail at even approximating well-ordered science and begin reinventing those institutions to better match the needs of a scientifically advanced, technologically sophisticated democracy: one that faces internal and external adversaries who are equally advanced and constantly evolving.

… And the first step in that process is to abandon the notion of a popular vote as the proper way to adjudicate issues that require expert knowledge.

That’s quite a conclusion, but it’s hard to argue with, given the results, and consequences, of recent popular votes.

(This recalls some of the ideas of Jonathan Rauch, too.)