Over the weekend I spent some time glancing through one of the dozen or so books I kept from my father’s small library. He was an architect, an idealistic and eventually disillusioned architect, who had great ideas but became relegated to routine corporate industrial projects. (The reason my family moved — or one reason I should say — from Southern California to Illinois, in the suburbs west of Chicago, for three years, from 1968-1971, was for his work on the Batavia Accelerator, what’s become known as Fermilab.) (And he told me more than once — never become an architect.)

The book I’m looking at, published in 1946 (a $3.95 hardcover, with many b&w pics!) is called TOMORROW’S HOUSE, and is addresssed to families of that era planning to buy or build a new home. What’s remarkable is that the ideas and photos in this book look only slightly dated; I think this book was at the foretrend of the ‘modernist’ thinking of the mid-20th century, when ‘traditional’ values (in terms of architectural styles, at least), were being re-thought. The designs of Frank Lloyd Wright are mentioned throughout, and they are in no ways dated; if anything, they are today rare and valued, and subjects of efforts by preservationists to keep homes designed by him, and other mid-century architects, from being torn-down (as ‘tear-downs’) by rich people who have no appreciation for the original designs and only want a property to build something much larger on… This has been a theme in news stories in LA and Palm Springs. (In fact, Ray Bradbury’s house was victim to the similar trend of ignoring culturally valuable sites in favor of the newer and bigger.)

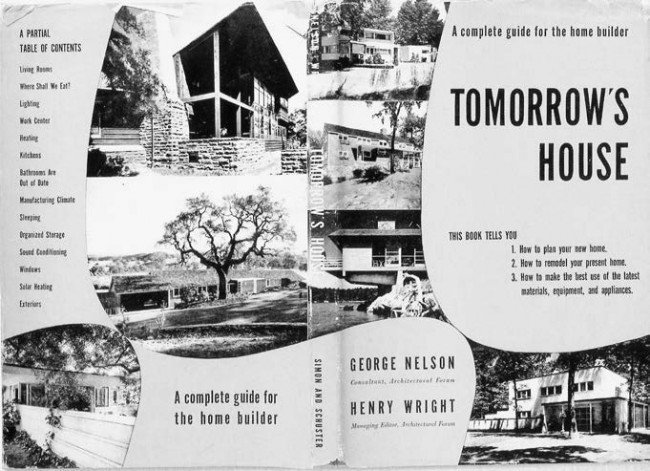

The book I’m looking at, published in 1946 (a $3.95 hardcover, with many b&w pics!) is called TOMORROW’S HOUSE, and is addresssed to families of that era planning to buy or build a new home. What’s remarkable is that the ideas and photos in this book look only slightly dated; I think this book was at the foretrend of the ‘modernist’ thinking of the mid-20th century, when ‘traditional’ values (in terms of architectural styles, at least), were being re-thought. The designs of Frank Lloyd Wright are mentioned throughout, and they are in no ways dated; if anything, they are today rare and valued, and subjects of efforts by preservationists to keep homes designed by him, and other mid-century architects, from being torn-down (as ‘tear-downs’) by rich people who have no appreciation for the original designs and only want a property to build something much larger on… This has been a theme in news stories in LA and Palm Springs. (In fact, Ray Bradbury’s house was victim to the similar trend of ignoring culturally valuable sites in favor of the newer and bigger.)

I had thought to do some scans and post some photos, but it turns out (everything is on the internet!) Google Images on this title has a fair number of images of the cover and interior illustrations: Google Images: Tomorrow’s House George Nelson. Well, several images.

I’ll record one family incident, for the sake of my own siblings and their descendants. My father’s father lived in a small house at the corner of a small town, Cambridge, Illinois, having spent his career as a farm-hand; his house had two floors and a basement, but not a fireplace. My father had a brother, Bruce, who moved to some Chicago suburb and worked as a high school shop-teacher his whole life, and had three sons who, last I heard, became missioniaries (I don’t know in what sense). My father’s sister, Betty, never left Cambridge; she married Stanley, who worked his life as the butcher in the one market in town. She was fat, he was thin, just like in that nursery rhyme. They had five kids, the second of whom, Christine, was almost exactly my age; and while they rented a house in town for many years, eventually they built their own house… right next door to my grandfather, Betty’s father. My father, the architect, volunteered to design a custom home for them. I even remember seeing the floorplans — what we would today call an ‘open floor plan’, with a large center room, the kitchen and dining off to one side, and a partial wall separating the main area from the row of bedrooms at the back. Betty and family rejected it and built two-story house from generic plans instead. And Christine, years later, built another home with her husband, on the far side of her parents’ home. They’re all visible through Google Maps, in this day and age. I haven’t been to Cambridge since 1992, to attend my grandfather’s funeral.

That small town of Cambridge, where I lived for a summer in 1968 and visited many times over the subsequent three years, made a deep impression on me. It was an idealistic small middle American town. In particular, among other things: as I discovered and read Ray Bradbury books at that age, I identified his “Greentown” with Cambridge. It fit perfectly.