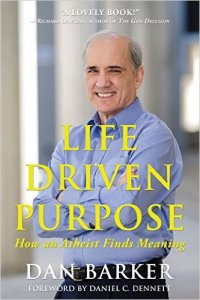

Dan Barker’s Life Driven Purpose (Pitchstone, April 2015), is much more cheerful than Lindsay’s book just reviewed. It’s an explicit response to religious superstar Rick Warren, and his ‘purpose-driven life’, in which everything about your life is in service to God — none of it is yours, beyond the trivial details of, well, everything about your life. Because your life isn’t about you, it’s about Jesus.

Dan Barker’s Life Driven Purpose (Pitchstone, April 2015), is much more cheerful than Lindsay’s book just reviewed. It’s an explicit response to religious superstar Rick Warren, and his ‘purpose-driven life’, in which everything about your life is in service to God — none of it is yours, beyond the trivial details of, well, everything about your life. Because your life isn’t about you, it’s about Jesus.

The subtitle of Barker’s book is “How an Atheist Finds Meaning” and so it echoes a number of other books, basically boiling down to: you find meaning in your interactions with other human beings, and not in some mythology about some god figure in the sky.

Barker uses some striking rhetorical flourishes. In Chapter 1, he describes a hypothetical man on a roof shouting at passers-by about how he has sent his son down in a basement to be tortured, in order to convince that passer-by that he, the man on the roof, should be worshipped.

All your have to do is come up here on my porch and thank my bleeding son for what he did for you. Tell him you love him. We’ll forgive your arrogance. Give us a big hug, and come into my housse, and we’ll live up in the attic [[ by which he means heaven, of course ]] together, and you can spend an eternity of gratitude telling me How Great I Am, while your ingrate friends and relatives are screaming down in the basement.

Which captures the incoherence of Christian theology, in my view, as I’ve mentioned before. Such beliefs and theologies are not coherent; they serve evolutionary, survival motivations for tribal cohesion, mostly.

What especially struck me about this book is the analogy of religious subservience, and Christian theology in particular, to the slave-mentality, which is something I’ve thought for years. The idea that there is a god who needs both to be *worshiped* and *feared* is like the slave who both fears his master yet nevertheless praises him, no matter what happens, no matter how harshly he is treated — because it could have been worse! Hurricanes, tornadoes? The survivors praise God for their survival, but never criticize him for their travails. (The nonsurvivors are dead, of course, and have no say.)

Barker, p27.5:

Asking, “If there is no God, what is the purpose of life?” is like asking, “If there is no Master, whose slave will I be?”

The theme of the book is that there is no purpose *of* life — but much purpose *in* life, which one can find for oneself; a purpose that might find you. This is great news: you can create your own purpose. Purpose comes from solving problems. Author describes a job he had as a programmer, and dealing with bugs; how that “state of uncertainty” can always be overcome, sometimes by avoiding the problem, simplifying the system. (This echoes my own comments about how programming and computer science are so ultimately fulfilling, because *any* problem can eventually be solved.)

A striking portion of this book is in the early chapters where Barker cites Paul of the New Testament epistles — which I’ve just been reading, coincidentally. Paul mentions how people are “empty pots” who are only fulfilled through the presence of Jesus. Barker’s characterization: “If you think your purpose must come from outside yourself, you are a lifeless implement or a slave to another mind.” p22.8

Barker’s Chapter 3 is about “Religious Color Blindness”, in which he attempts to characterize the believer’s mind: as binary, or polarized, unable to see shades of gray, and authoritarian. Thus concepts of sexuality, geology, evolution, language, abortion, there are no gray zones, no nuances, nothing to be interpreted — everything is right or wrong, black or white, and only their opinions on the matter are correct.

Chatper 4 is about the “deepity” question (i.e. it suggests it is about a genuine subject when it may just be the wrong question) of why there is something rather than nothing. The standard religious answers beg the question, or appeal to the god of the gaps — whatever we don’t currently completely understand must be due to God — which of course is continually shrinking. I like his comment about how Bertrand Russell and others dismiss the ontological argument (a perfect being must necessarily exist) as basically a matter of bad grammar is to apply the same argument to any other perfect thing we can imagine (e.g. a perfect island, observed Anselm).

The final chapter returns to the book’s main theme: there is meaning *in* life rather than *of* life. To find meaning in life, learn something, or create something.