Kirk faces court martial over the death of a crewman with whom he had a history, in a confrontation that pits human rights against a computerized culture.

- The enhanced graphics are especially effective in this episode, showing both the Enterprise and another starship in orbit around this starbase, a shuttlecraft flying past, and even repair crew at the hole in the Enterprise hull where the ‘pod’ that was jettisoned had been (something we never saw in any way in the original episode). Given that this is a starbase, and we shortly see a chart of some dozen starships and their maintenance status, it’s nice to see more than just the Enterprise in orbit.

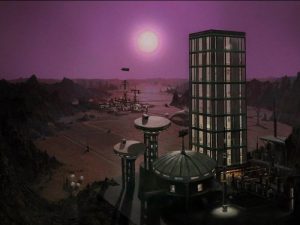

- Also much improved: the groundside views of the starbase, with narrow mushroom-like towers in the distance. One shot at the beginning of one of the acts shows a ground-view promenade with pedestrians, amidst those towers.

- The Enterprise is at the starbase for repairs due to damage suffered in an “ion storm,” whatever that is. I never got the impression that the producers or writers had any idea what that was (as with Lost in Space and their “cosmic storms”).

- Much more is made here of the loss of a crewman in that storm than we ever see about the death of any other crewman throughout the series.

- This episode has two or three fundamental implausibilities that can’t be rationalized. The first is why there’s an issue about jettisoning the pod before or after going to red alert. Both events are results of Kirk’s subjective judgment of the danger at any given moment. What is there about a red alert that allows Kirk to jettison the pod? Just a permissions thing?

- The second implausibility is at the heart of the episode’s debate over human rights versus machines. Everyone presumes that computers can’t be wrong. If the “computer transcript” says something is so, it must be so. But the evidence from the computer that impugns Kirk isn’t any kind of electronic log of what happened when – it’s a frame from a video recording of what happened on the bridge, showing Kirk’s finger punching a button labeled (conveniently) “jettison pod”. (As if that’s something so routinely done that it needs a dedicated button on the captain’s chair.)

- Which leads to the biggest implausibility – that Finney, the records officer, somehow having altered that image to implicate Kirk (whom he blamed for reporting an error that Finney made years before, crippling his career), also accidentally altered the computer’s chess programming, as Spock deduces by playing several games against the computer and repeatedly winning. What do they have to do with one another? (You have to conclude that familiarity with what computers actually were was very hazy among Hollywood scriptwriters back in the mid 1960s, a theme that would recur through this series, and undercut an otherwise very dramatic 2nd season episode, “The Ultimate Computer”.)

- And then there’s the silliness about how they locate a man presumed dead who is instead hiding somewhere aboard the ship: They beam down virtually the entire crew to get them off the ship, leaving only senior Enterprise staff, and the courtroom officers and lawyers, on the bridge, and McCoy produces a device that one by one ‘removes’ the sound of their heartbeats from the cumulative audio feed of all sounds aboard the ship. Well, not all sounds — not their breathing, not any noise from walking around, not their voices. It’s dramatically played, as McCoy finishes and… there’s one heartbeat left! – but it’s a ridiculous way to locate a missing crewman.

- There are also plot infelicities. How the beautiful woman Kirk encounters in the starbase’s lounge, Areel Shaw, is an old flame of his – and also the attorney who then prosecutes his case. How the best defense lawyer for the job, the eccentric Samuel T. Cogley, happens to be available on the starbase (never mind the anachronism of how Cogley values physical books over computers). And how Finney’s daughter, Jamie, also happens to be here at this starbase. And how her attitude toward Kirk abruptly changes part way through the story [this is in part due to scenes that were written but cut due to time constraints].

- Cogley does have some good lines, as when he speaks passionately for Kirk’s right to be confronted by the witness against him (i.e. the computer): “Rights, sir. Human rights! The Bible, the Code of Hammurabi, and of Justinian, Magna Carta, the Constitution of the United States, Fundamental Declarations of the Martian Colonies, and Statutes of Alpha Three.” Suggesting that even our venerated Constitution might be overtaken by later documents.

- But Kirk has the best lines, or at least Shatner makes the best delivery, as when he defends his actions in testimony, measuredly, frankly, unapologetically, firmly: “Given the same circumstances, I would do the same thing without hesitation. Because the steps I took, in the order I took them, were absolutely necessary if I were to save my ship. And nothing… is more important than my ship.”

- A bit of mathematical illiteracy: as the ship’s orbit begins to decay (they were maintaining “orbit by momentum” but apparently that doesn’t last long) Spock says something about “on the order of one to the fourth power.” Yup.

- Two more understated dialogue deliveries that endure. First, as the court reconvenes aboard the Enterprise, it is Cogley who first suggests that Finney may not be dead after all, but hiding. Is there room to hide aboard a ship this size? Kirk, stunned by the implication of this suggestion, almost whispers “Possibly.”

- And later, as the one heartbeat is left on the audio, Commodore Stone concludes, rather stonily, “So, Finney is alive”, and Kirk quietly replies with only the barest trace of vindication, “It would seem so.”

- And then we have the requisite fist fight, as Kirk finds and confronts Finney, who’s been alive all along. [There was a filmed but omitted scene in which Cogley brings Jamie on board to help subdue Finney, which explains Cogley’s quick exit from the bridge with some errand to run in the previous scene.]

- And finally, after Finney is subdued and the Enterprise is saved and the case against Kirk dismissed, we have Kirk kiss Areel on the bridge, for old time’s sake, as she departs. The crew around them are careful not to react. Then Kirk sits in his chair, and says defensively to Spock and McCoy, “She’s a very good lawyer”. And they respond impassively, “Obviously” and “Indeed she is”. The abruptly cheerful music underscores this bit of closing Gene Coon humor.

Blish’s adaptation, in ST2:

- Blish’s version of this story seems to be derived from a draft or two before the final script. Kirk’s romantic background with Areel is missing; the key issue is whether the ship was a “double red alert” rather than just “red alert”; and Finney, at the end, doesn’t sabotage the ship, requiring Kirk’s quick work to repair it.

- Rather, we get a better resolution of the subplot concerning Jame, Finney’s daughter. In the broadcast script we see her twice: at the very beginning, angry at Kirk for apparently killing her father; and then later, when she’s much calmer and concerned for Kirk’s well-being. She explains her change of attitude as the result of having “read through some of the papers he [her father] wrote, letters to mother and me.”

- Blish saves those lines for later, and has Jame show up on the ship just as Kirk finds Finney in engineering, resolving that scene in an emotional, rather than violent manner.

- This may be a case where a character-development plot was sacrificed for the sake of a fist-fight – between Kirk and Finney – an action sequence that NBC always appreciated.

- Blish retains most of Cogley’s speech about the rights of men in the face of the machine, but omits the specific examples given in the final script: “Rights, sir. Human rights! The Bible, the Code of Hammurabi, and of Justinian, Magna Carta, the Constitution of the United States, Fundamental Declarations of the Martian Colonies, the Statues of Alpha Three.”

- Blish does not try to rationalize what I’ve always felt were two huge flaws of this episode: how the altered video of the ship’s bridge, when it was or was not at red alert, has anything to do with changed computer logic for playing chess; and the clumsy, implausible manner of locating a missing crewman, by masking out the heartbeats of the last few others left on board.