This short novel is from the late 1950s, and is the first of four novels for which Heinlein won the Hugo Award. It’s short and snappy, notable in part because it’s not essentially a science fiction novel. It’s about politics and an actor/impersonator, and the SFnal passages are interesting, but not crucial to the plot.

This short novel is from the late 1950s, and is the first of four novels for which Heinlein won the Hugo Award. It’s short and snappy, notable in part because it’s not essentially a science fiction novel. It’s about politics and an actor/impersonator, and the SFnal passages are interesting, but not crucial to the plot.

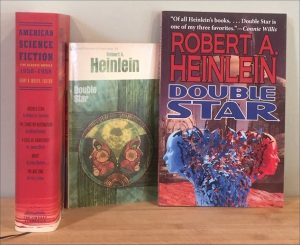

(The photo shows the 2012 Library of America omnibus of American Science Fiction: Five Classic Novels 1956-1958, edited by Gary K. Wolfe, where this novel fills the first 147 pages, and to which page references below refer; the Signet paperback edition I bought in 1972, for $.60, with a cover by Gene Szafran, running 128 pages (though I’d read it earlier, in 1970, from the library); and a more recent 2015 trade paperback edition from Phoenix Pick, running 167 pages.)

The story, in brief: the first-person narrator is Lorenzo Smythe, a down-on-his-luck actor who nevertheless thinks very highly of himself. The setting is (presumably) some hundreds of years in the future when the Moon has been colonized and intelligent races have been discovered on Venus and Mars, while a human Emperor rules the solar system from the Moon. As the story opens Smythe is sitting in a bar watching how spacemen walk – slightly leaning forward, etc. (in an off-hand speculation about future astronauts and living in zero G). He meets a man who offers him a job, not acting exactly, but to impersonate someone, a job that should last only a few days.

Despite some reservations Smythe finds himself on his way to Mars, only then learning that his job is to impersonate Bonforte, a leading politician and head of the Expansionist part, a man loved and hated throughout the solar system. The real Bonforte has been kidnapped, yet must attend a crucial ‘adoption’ ceremony with the Martians, who have an extremely rigorous, stylized system of hierarchical rituals and manners. Smythe is tutored by Bonforte’s secretary Penny, and he succeeds in the impersonation at this ceremony.

The plot then ramps up, again and again. The real Bonforte is found, but damaged; Smythe is persuaded to keep playing his role, studying Bonforte’s speeches and Expansionists’ policies to be able to speak to the press. On the Moon he meets the Emperor – an old acquaintance of Bonforte — who understands. And so on…

[[ spoiler!! ]] The real Bonforte has a stroke. Smythe takes his place indefinitely. An aide defects and tries to expose Smythe; Bonforte dies, yet wins the election, and Smythe becomes him. The story we’ve read is from 25 years later, as Smythe looks back at his – at Bonforte’s – career.

\\

Given the story there’s not a lot in this book, compared to some of Heinlein’s others, that speak to big themes of history or science or philosophy.

One takeaway is the political system, described in some detail in the Wikipedia entry (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Double_Star), and in particular the political conflict between the ‘Humanity’ party, which favors continued domination of humanity over other races in the solar system, and the ‘Expansionist’ party, which favors expanding rights to include other intelligent species. The distinction is echoed by the current tensions between nationalists and globalists in our current era, of course. And the distinction characterizes a story arc in which Smythe is initially a Humanist, and despises Martians for their appearance and behavior, and as he’s forced to understand and espouse Bonforte’s views, becomes more sympathetic with them.

A second is the exotic nature of the Martians, the only intelligent aliens we see in the book. Each Martian belongs to a ‘nest’ and carries a ‘life-wand’; they have ‘conjugate-brothers’; their language reflects their complex social system, e.g. “High Martian is polysynthetic and very stylized, with an expression for every nuance of their complex system of rewards and punishments, obligations and debts.” (p48). And how the Martians split via fission to reproduce, taking “almost five years, after fission, for a Martian to regain his full size, have his brain fully restored, and get all of his memory back.” This is all fascinating, if almost gratuitous given the nature of the plot, but a good example of science fiction imagining intelligent species that aren’t simple analogues of ourselves.

\\

Other interesting notes and quotes:

- Heinlein as always is convincing and authoritative; he always seems to know what he’s talking about, whether it’s about politics or torture or how governments really work. (At the same time, the fp pov isn’t always appropriate to this expertise; why should an out of work actor know so much, or care, about the history of brainwashing?)

- People still light cigarettes, even on space ships.

- p80.4, a cute line about kittens: “The trouble with adopting a cat is that they always have kittens.”

- p87b, “Politics is a dirty game!” “No, there is no such thing as a dirty game. But you sometimes run into dirty players.”

- p121.3, how politics is the only sport for grownups: “Brother, until you’ve been in politics you haven’t been alive. It’s rough and sometimes it’s dirty and it’s always hard work and tedious details. But it’s the only sport for grownups. All other games are for kids. All of ‘em.”

- p125b, how political rallies are only for the converted: “There are no new votes to be picked up by personal appearances at political rallies. All it does is wear out the speaker. Those rallies are attended only by the faithful.”

- p146b: “The people will take a certain amount of reform, then they want a rest. But the reforms stay. People don’t really want change, any change at all—and xenophobia is very deep-rooted. But we progress, as we must—if we are to go out to the stars.”