Isaac Asimov began publishing stories in magazines in 1939, but his first book wasn’t released until 1950, and that first book was his first proper novel, PEBBLE IN THE SKY. By 1950 however he had published in the magazines all the stories that went in to the collection (or story-cycle) I, ROBOT, his second published book also in 1950; and all the stories that comprised his so-called “Foundation Trilogy” published in three books, FOUNDATION, FOUNDATION AND EMPIRE, and SECOND FOUNDATION – his 4th, 6th, and 9th published books, according to his own list in OPUS 100, his 100th published book.

The chronology of his magazine stories and book publications suggests that, having finished his final Foundation story for Astounding Stories, a serial that ran in late 1949 and Jan 1950, he immediately sat down and wrote his first novel-length work, PEBBLE IN THE SKY, published later in 1950; he moved from writing long tales for magazines, to longer tales for book publication. Two more novels subsequently followed in the next two years: THE STARS LIKE DUST and THE CURRENTS OF SPACE. In 1952 he also launched his juvenile series with DAVID STARR SPACE RANGER in 1952 (discussed in a previous post). The balance of the decade saw three collections of earlier (unrelated) published stories; three more novels, the two robot novels THE CAVES OF STEEL and THE NAKED SUN and a complex time travel novel, THE END OF ETERNITY; and, oh yes, a non-sf mystery novel, THE DEATH DEALERS. By the end of the decade he’d set fiction writing mostly aside, in favor of nonfiction books for general audiences. He’d published 32 books by the end of 1959; 20 science fiction books, and 12 nonfiction books. (In the entire next decade, he published just 7 science fiction books, including 2 anthologies; and 61 nonfiction books.)

So the SF novels in the ‘50s fall into distinct groups: the three FOUNDATION books; the six LUCKY STARR books; two robot and one time travel novels; and the three published in the early ‘50s. Those last three came to be called the “Galactic Empire” novels, because they all involve, at least incidentally, Earth, but are set in a future in which humanity has spread onto planets throughout the entire galaxy. Still, it is an era long before the unification of the galaxy into the Galactic Empire of the Foundation novels. These three novels have seldom been out of print in all these years, but have never enjoyed the popularity or acclaim of the Foundation stories, the robot stories and novels, or END OF ETERNITY.

I reread them (for the first time in decades) in the past couple weeks, and they’re interesting enough. Actually, far from being a trio of similar novels, they strike me as having quite different strengths and weaknesses. I’d give PEBBLES a B, STARS a C, and CURRENTS an A, which wasn’t what I’d expected when I sat down to revisit them.

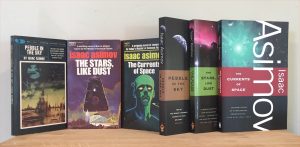

The photo shows the mass market paperback editions I bought from 1968 to 1972, the first a Bantam Pathfinder edition, the second and third from Fawcett Crest, with the worst cover on the best book; and the recent trade paperback editions from Tor, which I read just now. Old mass market paperbacks used tiny print and compressed pagination, I suppose for economy; the more respectful modern editions relax the fonts and paginations. Thus, ironically, the smaller mass market paperback of CURRENTS ran 191 pages; the larger trade paperback of same runs 239 pages.)

*

The opening pages of PEBBLE IN THE SKY are the most memorable of anything in the three. Joseph Schwartz, a retired tailor, walks down a street in Chicago, quoting Browning to himself (“Grow old along with me…”). Meanwhile, at a nearby Nuclear Research facility, a hastily cut-short experiment sends a beam of *something* that cuts a hole through the walls and outward into the city—

And Joseph Schwartz finds himself in a grassy field with no houses in sight. Schwartz has been cast into the far future, still on Earth, but in an unknown society and circumstances.

Asimov tells the story with chapters that alternate between several sets of characters, as he does in all these books. So the novel develops with several parallel plot strands that, rather coincidentally, intersect.

- Schwartz stumbles upon the home of Loa Maren, her husband Arbin, and her father Grew, living in an isolated house away from the city. He cannot speak their language and so they think him an imbecile, or perhaps an Outsider spy. They decide to unload him onto a scientist at the Nuclear Institute in the city nearby city Chica (the city names have distorted over the centuries, but not the name of the Nuclear Institute!) who, according to the papers, has developed a device called a Synapsifier, to improve learning. It hasn’t yet been tried on humans, and the scientist, Shekt, is looking for human volunteers.

- Meanwhile, an archaeologist from Sirius, Bel Arvardan, arrives on Earth to look for evidence of his pet hypothesis: that humans from all the planets in the galaxy originally evolved on a single planet — a radical, unpopular idea — and that planet is Earth. Ironically, we come to learn, there’s a political sect on Earth who believes the same thing.

- The Procurator of Earth (that is, the representative of the Galactic Empire who lives on and oversees Earth), Ennius, who lives in an elaborate artificial estate on a plateau near Mt. Everest, worries about rebellion by the locals. Earth is highly radioactive in some areas, the result of some long-age war, and Outsiders, humans from the rest of the Galaxy, think Earthmen are feeble and disease-ridden. Because resources are limited on Earth, a custom called The Sixty has arisen, by which anyone reaching that age is obliged to sacrifice his life; a few talented scientists and other privileged people are exempt. Ennius learns of Shekt’s device and wonders if it might be made available to the Empire.

Then things develop.

- Schwartz is subjected to the Synapsifier and not only survives, he quickly learns the language, and develops a ‘Mind Touch,’ a telepathic awareness of others around him and what they are thinking. He escapes from the Institute.

- Arvardan is shadowed by an agent of the Brotherhood, the sect who believe Earth is humanity’s home planet.

- Earth’s High Minister, a puppet under control of his secretary, Balkis, hears of the confluence of the Outsider [Schwartz], Shekt’s device, and the archaeologist Arvardan, and thinks these can’t all be coincidences—there must be a conspiracy afoot.

The plot of the novel is entirely circumstantial – that is, driven by coincidence. Yet twice in the book the bad guy, Balkis, takes coincidences as evidence of conspiracies! This may be Asimov mocking his own jury-rigged story, yet it may also illustrate how nationalistic zealots driven by fear and hatred are also prone to conspiracy thinking.

(spoilers follow)

- Shektz, whose work has been suppressed by the Brotherhood, meets Arvardan and reveals Earth’s plan to dominate, or even exterminate, the rest of the galaxy. How? By releasing a virus that Earthmen have developed an immunity to (because the radioactive environment) but which the rest of humanity has not.

- But they are caught and arrested, and taken to the same jail where Schwartz has been recaptured to. (More coincidences!) Schwartz reveals he cannot only read minds, he can control others’ bodies, and so they stage a jailbreak by taking control of the evil secretary Balkis and simply walking out in front of all the guards. And they learn from Balkis’ mind that the attack on the galaxy will consist of missile launches in just a couple days. [How do these missiles travel in space and will so easily travel great distances across the galaxy? In other books Asimov describes hyperspace jumps, but they are assumed here.]

- And so Shektz and his daughter Pola, Schwartz, and Arvardan, with the captive Balkis, head for the missile base, and demand that the Procurator Ennius be brought and informed of the plot. Ennius is brought, but refuses to believe the Earthman plot, and does nothing.

- In an anticlimactic conclusion, Arvardan wakes the morning after the deadline and learns that Schwartz escaped the meeting the night before, took control of an airplane pilot, and bombed the missiles himself. But he, and we the reader, learn this in retrospect.

Along the way,

- There’s a romantic subplot between Arvardan, the Sirian, who fights his prejudice against filthy Earthmen, and Shekt’s daughter Pola, who finds him attractive but thinks he’s contemptuous of her. Soon enough they admit their love for each other. There’s an identical subplot in the next book.

- Asimov plays the coincidences for dramatic laughs as a minor character from early on shows up near the end, in a position to take a revenge and foil the good guys’ victory – and then is used by Schwartz to foil the evil plot.

- The idea that humanity has forgotten not just that the entire race derived from a single planet, but even which planet that was, is a tad incredible, though Asimov tries to explain the logic behind the so-called ‘Merger’ theory. It seemed more plausible from the perspective of those in the early Foundation stories, far away, for whom the mere existence of Earth was a legend.

So: a pleasant enough book, but driven by coincidence and circumstance. It benefits from the romantic situation of Earth being a remote and nearly forgotten world in a far-future galaxy entirely populated by the human race. But there’s not much intellectual content. Learning machines and telepathy are pulp SF devices (now long-discredited). The most provocative ideas are political, reflecting historical models, as Asimov has admitted about these early books. Thus the Procurator, and High Minister, the uncomfortable relations between locals and outsiders, and the conspiracy tendencies of zealots.